By Rachael Watcher

NEOPAGAN, INDIGENOUS, AND EARTH-BASED SPIRITUAL PRACTICE

So much of what we think of as “prayer” comes out of a social experience that is informed by the Abrahamic religions, that we often forget about how our indigenous brothers and sisters approach their conversations with the Creator. For most of my younger life I was taught that prayer was something used to open important ceremonies or said in church or temple. A public prayer would generally take a few minutes of time standing or sitting with head bowed, hands clasped together in my lap, sometimes speaking the words along with everyone, sometimes having someone speak for us as we contemplated the words and their meaning.

In the Abrahamic traditions, words – in prayers, psalms, meditations, zikrs, and chants – are a critical component, a primary means of access to Deity. Neopagan, Indigenous, and related Earth-based traditions, are utterly different in their approach to Deity. Until I became deeply engaged in interfaith dialogue I did not even think to approach what we do from the standpoint of “prayer,” for at least three reasons.

- We do not refer to our spiritual practice as prayer.

- In ritual we do not equate sitting still and allowing someone to talk for us or with us with connection with deity. Our connection, while a shared, active experience, is often very personal and varies in form for each person in the ritual.

- When we enter into ritual the entire process is the “prayer.” There is no distinction between the ritual that we are performing and our communication with Deity. From here on, I’ll be talking about ritual rather than prayer.

As I began to practice ritual with other Pagans, including Hindus and Pan American First Nations peoples, I began to realize that our ritual, in both intent and practice, shares much of what prayer is about, though our approaches are radically different. Pagan ritual, as with the sacraments of most religions, is celebratory, supplicatory, initiatory, or dedicatory. That much we share. Where and how do we differ?

The Power of the Circle

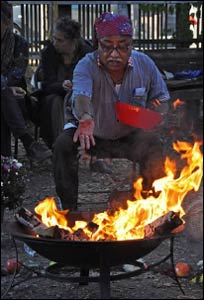

The critical component in our traditions is the circle. In a circle everyone faces each other. Outside, a fire is built within the circle. Inside, everyone faces the center where sacred tools and symbols are laid. A common greeting among people of the Earth is “You are welcome at my fire.” In the circle we can each see and recognize every other person present, knowing each of us will be working together to raise and hold that energy, keeping the circle open and sacred to its purpose. Each of us is an important, active participant.

Francois Paulette

Francois Paulette, a Dene Suline and a member of the Smith’s Landing Treaty 8 First Nation of Canada, attended the 2009 Parliament of the World’s Religions in Melbourne. On two occasions, when asked to open the day’s meeting, he said, “Folks, I am very uncomfortable here with these rows of chairs. We work in a circle. Let’s all create a big circle so that we can see each other.” We use our ability to see and feel each other’s presence as a battery holding the energy of our “working” as we would call it, or prayer as others might use the term.

For Neopagans, the creation of this circle sets us apart from normal time and space, moving us to a space between the realms of humankind and Deity. Further, this place is “a space between the worlds and time,” a more equal place for the meeting of Gods and mortals. Within this space we sing, dance, make offerings, and invite the Gods to join us. We believe that, having invoked the presence of the Gods, they are, in fact, present within the circle. Everything that we do is an act of communion with them.

Last month’s TIO noted how 200 years ago the Anglican cleric John Newton, author of “Amazing Grace,” wrote:

“The chief fault of some good prayers is that they are too long; not that I think we should pray by the clock, and limit ourselves precisely to a certain number of minutes; but it is better of the two, that the hearers should wish the prayer had been longer, than spend half the time in wishing it was over.”

I have Christian friends who give his argument thumbs up.

A Different Sense of Time

Tata Apolonario Chile Pixtun

Newton’s point dramatizes the contrast in our viewpoints. In a fire ceremony presided over by Tata Apolonario Chile Pixtun, a Mayan Elder and community leader, the difference is clear. Tata was holding this ritual in the backyard of a Southern California suburb. Attending were mostly Americans of a European ethnic background being exposed for the first time to such a ritual. After the first hour folks began to squirm. By the second there were not so subtle glances at watches. Finally Tata said (in translation),

“Look, I see you all glancing at your watches, but forget that. This ritual will take as long as it takes. Settle down and develop a proper attitude toward the spirits of the place.”

In many Indigenous and Neopagan rites and rituals, we do not allow time-pieces. Our frame of mind is in a place between the worlds, and time has no reference in such an altered state.

For most indigenous practitioners, a four-hour ritual is considered a short time to enter into the proper attitude and mind set for hearing and speaking to the Gods. I have attended rituals where we were in circle for 36 hours. A Haidu elder confided in me that she was constantly being asked by “white folks” for invitations to a ritual. She said that she “never did invite them” because she knew that without a willingness to believe in, or an understanding of what was being celebrated, they’d be bored in half an hour and their attitude would totally disrupt the process.

Neopagans, by contrast, are an interesting mix of practices. While we normally hold much shorter rituals, influenced by our western European background, we still approach ritual in a manner similar to the description above.

For us the Gods are expressions or manifestations of a pantheistic and, for some, a panenthistic cosmos. They are immanent as well as transcendent, and between us there is reciprocity. That is to say, we do not ask the Gods to do our work for us but rather to join in the work we do. We know that they are always near and listening as a result of the reciprocal relationship we have cultivated. We offer our energy to, and belief in them, and they, in turn, offer their support in what we ask of them.

We expect that our requests will be answered in some clear manner, whether it be yes or no. A friend, Gus diZerega, said that the sure sign of an affirmative response is the rapid accumulation of meaningful and appropriate coincidences. We place our trust in the Gods that we serve to know better than we what it is we really need and seldom find it necessary to ask. We assume that it is within our power to provide for ourselves, and the Gods will take care of the rest.

I asked the Gods to allow my hair to grow out healthy. I had undergone many operations and a heavy regime of medications, pretty much frying my very fine hair to frizz. After two years it was showing no hope of recovery. I promised the Gods that if my hair were allowed to grow, I would not cut it again except in the most minimal way, to keep it healthy. It almost immediately began to grow out and within a couple of years was well down my back.

Then I unexpectedly got a professional position again, and my hair simply did not look right for what I was doing, no matter how I tried to fix it. So one evening I sat down within my ritual space and had a conversation with those same Gods, explaining my situation and asking for a sign to be allowed to be released from my promise not to cut my hair.

The next day I was sitting at my desk at the real estate office where I worked and a gentleman came in, seeking some information on property in Puerto Rico. We couldn’t help him much. But then he walked over to me, took my hair down, without permission, and combed his fingers through it. “This needs to be cut” he said, “I’ll give you 40 percent off if you’d like me to do that for you.” He dropped his card on my desk and walked out. It turns out that he was, and is, one of the best stylists in San Francisco. How would you interpret that? I had my hair cut the following day, being careful to offer my thanks that very evening for such a quick and clear answer to my request.