By Malcolm Clemens Young

ONE OF THE LARGEST RELIGIOUS RITUALS IN THE WESTERN WORLD

I spent the week before Labor Day away from the church I serve, participating in Burning Man. Every year in the dust of a dry lakebed at 4,000 feet elevation, volunteers build from scratch a temporary city, this year with a population of 68,000 people. The site lies 110 miles north of Reno, Nevada, accessed by only a single lane road through the physically punishing desert.

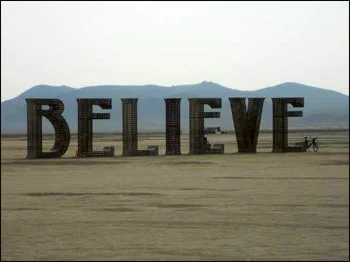

Laura Kimpton and Jeff Schomberg created the ‘Believe’ art-installation at Burning Man this year.

We all had different motivations for being there. I went to become a temporary citizen of another country with different rules and values. In our culture we can feel powerless to make our world more humane. It may be difficult to even imagine alternatives to pictures of reality that limit or distort us. Burning Man helps me to see new possibilities for being with others and embracing their holiness.

A similar energy motivated the Desert Fathersand Mothers of the fourth and fifth centuries, whose spiritual breakthroughs ultimately led to the invention of Western monastic life. Those early Christians wanted to explore alternatives to the cruelty, slavery, exploitation, and arbitrariness of the dominant Roman culture. I went for similar reasons, to experience an alternative to the consumerism, bureaucracies, and hierarchies that color every interaction we have with each other.

Grounded in Generosity

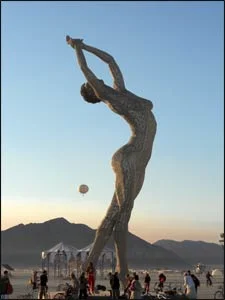

The sun sinks behind “Vision Quest,” the creation of Michael Hayward.

The desert monks articulated rules that governed their lives together. Burners similarly have ten principles written by Burning Man founder Larry Harvey. These include: radical inclusion of everyone, generosity, freedom from commerce (no buying, selling or even displaying corporate logos), self-reliance, self-expression, community, responsibility, environmental stewardship, participation and the value of immediate experience.

Burning Man will not cure all the ills of a broken, decadent and unjust society. It is not a permanent replacement for our economic system. It is a temporary experiment in how we treat each other. It is a chance to step into a more generous place with different freedoms and constraints, hazards and blessings. We came from different worlds but shared one experience in common – generosity, hospitality, and openness to meeting new people.

The most striking element of this experience is giving. Walking down the street people gave me hotdogs, shaved ice, steak, pancakes, drinking water, beer, a telephone call home, clothes and costumes, Polaroid pictures, Pop Tarts, jewelry, fresh peaches, entertainment, a newspaper, books, and music.

In the desert I saw hedonism and self-sacrifice, narcissism and generosity, indifference and grace, despair, self-destruction, and signs of wonderful new life. The people went there for different reasons and brought with them different expectations. The one thing we all shared was the radical giving at the heart of that community, a kind of hospitality that should inspire all people of good faith.

Religion at Burning Man

The Latin word “religio” is the root for our word “religion.” It means to tie, bind, or fasten in the way that you might moor a boat. In a world of coercive and persuasive powers that compel and draw us as moral, intellectual, and aesthetic beings, religion is the way that we seek orientation, or the mooring appropriate for our time and place.

The sheer size of “Truth is Beauty” by Marco Cochrane – you can see people wandering below the sculpture – gives a sense of the art objects at Burning Man.

We bind ourselves to others in the past and present, we become connected to them as we try to live as humanely as possible.

It is in this sense that I regard Burning Man as one of the largest religious rituals in the western world. We danced, created, and destroyed things together. We talked, cried, yelled, and sat in silence. We came to the holy desert from wildly different places, but even in our ecstasy and despair, mostly we were one – like the future city that John of Patmos calls the New Jerusalem. Burners greet each other with hospitality saying, “Welcome home!” For me this means, “express your wonderful uniqueness, because we act as a kind of family for each other.”

I talked about God with Vedic priestesses, Unitarians, yogis, Quakers, entheogen voyagers, Episcopalians, Hindus, Roman Catholics, shamans, atheists and Zen teachers. I met people there who hate Christianity, people who, often for good reasons, associate it with bigotry and condemnation. But this was a minor part of my experience. Mostly in that holy desert we shared what we have in common. In outlandish costumes, creating breathtaking works of art, building friendships, we tried to express more completely who we genuinely are. Perhaps for a short time we could even see ourselves and others more clearly as children of God.

Among the three hundred different official art installations, many explicitly employed religious symbols. On the Playa this year artists constructed at least four churches along with a variety of temples and pyramids.

Perhaps the most spectacular place we shared in common was “The Temple of Whollyness.” By the end of the week this pyramidal holy space, for prayer, meditation and yoga, had thousands of inscriptions written on it. These could be funny and thoughtful. Often they expressed pain like, “Let my dad be happy, and don’t let me go down the same path,” “I’m done living in my anxious past,” or “Mom and Dad. Please find it in your hearts to forgive each other. I love you.”

The ”Temple of Whollyness” was the creation of Greg Fleishman, Melissa Baron, and Lightning Clearwater III.

People wrote about searing losses. In this place they cried together and realized again that everything we know and love will one day die.

A young woman mourning the end of her eight-year marriage asked me to come and pray with her as she left a box of wedding memorabilia at the temple to be burned. The next night, as the shamans leaped and the chanters droned and the flames devoured the temple, she experienced this as a divorce ritual, a way of laying down burdens that she no longer needs to carry.

Inside the Temple of Whollyness was a major gathering place.

At times the dust storms, elevation, heat, and harsh desert conditions made us wonder why we were doing this. Still one could not help but feel a sense of elation in first arriving. Signs along the side of the road prepared us for the society we were entering. One said, “Finance is your religion.” Another quoted Arthur C. Clarke, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Not long after arriving I met a man with a yellow armband that said simply “Get Free!”

Together we were getting free from our shared religion of finance with a social technology that seemed like magic. For a whole week no one tried to sell me anything. There were no phones, schedules, email messages, advertisements, brands or logos. The only things one could buy were coffee and ice. The pace of Silicon Valley makes it difficult for us to be generous with our time. Out there it seemedlike we had infinite reservoirs of time and attention to share.

Bringing Burning Man Home

What did I bring home? Mystical experiences in the desert renewed my sense of intimacy with the divine. In the solitude of early morning, red slivers of cloud intersecting the rising sun made me feel like God was baptizing me in dust. Bicycling at sunset with the wind at my back, flying past extraordinary artistic creations into the gray water sky, this vast, mysterious universe seemed like a home for our peace, gratitude, and love.

Second, most of the people I met were younger and helped me see the world in a different way. I realized how sheltered and naïve I am. Usually when I talk to people in their twenties, it is on my terms, in my world, and this constrains our conversation. At Burning Man I got out of my suburban church box and met people who do not even really know what Christianity is, people whose motivations and most basic assumptions differ from my own. They deeply blessed me and helped me to appreciate our shared humanity.

Finally, perhaps it took getting out of my church sphere to discover what I have to offer to the world. The people I met showed me the value of being deeply immersed in an ancient spiritual and intellectual tradition.

Burning Man stands high above the ‘flying saucer,’ all of it burned the final evening.

On one of my last nights, in the middle of a dust storm, I met a woman named Susan. She had sought God when she was young and had given up. We wondered if everyone might know something about God even if we use different religions and language to describe the source of meaning. Perhaps truth is the collection of ways that God speaks to us.

In that conversation I realized that religions can offer ancient practices (art, prayer, service to others, the study of holy writings, music, ritual, a calendar, aesthetic experiences, and more) that help draw us more deeply into the Divine.

Burning Man also helped me see that spiritual practices from the past have no value unless they can be connected to the concerns and aspirations of the present. Of any group in society, the religious communities I know should be speakingto exactly the people drawn to Burning Man. Their openness to the future, their divinely inspired creativity, their idealism in seeking to transform society so that it is fair and accepting, their spirit of generosity and concern for others, are exactly what we need.