Interfaith at the Vatican

by Ruth Broyde Sharone

Pope Francis is known to be spontaneous – even impulsive – and Pope watchers inside and outside the Vatican are curious to see what interfaith initiatives of his own Pope Francis intends to launch in the coming years. In January this year, for example, a historic photo flashed across the internet: a kosher luncheon that Pope Francis hosted for 15 Argentine rabbis in the Vatican. So, too, 60 Minutes and other media recently focused on Pope Francis’ long-term, close relationship with his Buenos Aires friend and colleague, Rabbi Abraham Skorka, with whom the Pope co-authored On Heaven and Earth (2010).

Recently the Pope traveled to the Middle East with two Argentinean companions, Rabbi Skorka and Sheik Omar Abboud, a former secretary-general of the Islamic Center of Argentina, marking the first time in history that leaders of other faiths participated in an official papal delegation. A Vatican spokesman said the pilgrimage was both “an explicit signal” of the importance of interfaith dialogue and the “normality” of having friends of other religions.

Cardinal Tauran – Photo: La Stampa

“Expanded pluralism” is the hallmark of this period in history, says French-born Cardinal Jean Louis Tauran, the head of Pontificio Consiglio per Il Dialogo Interreligioso (the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue). He has served the Council in Rome for the last seven years and been a diplomat for the Holy See for 28 years in the Dominican Republic, Lebanon, and in Europe.

In short, Cardinal Tauran has been privileged to maintain a bird’s eye view of the Vatican’s role in interreligious engagement around the world, “Everything is conjugated in the plural today,” he says, “not just our religions but our philosophies and our ways of life.”

Cardinal Tauran doesn’t view diversity as a threat but a challenge – “a challenge given by God to see how we might collaborate for the common good and make this a more welcoming place for everyone.If we are a family, then we have to learn to get along with all of the members of the family, don’t we?” he asks rhetorically.

That means following a trajectory “from tolerance to friendship,” he elaborates. “The basis of interfaith dialogue then is to accept the otherness of the other, to listen to the other, to consider what he thinks and, in the process, to observe what divides us and what unites us. We don’t say all religions are the same, but every man and woman has to be fitted with shoes,” Cardinal Tauran says, underscoring “the sameness” of our personal needs and the exigencies of life we all share.

He points out that believers as well as non-believers have a place in the building of a just society, since we are all citizens of society.

Acknowledging the spotty record of religious behavior throughout history, Cardinal Tauran recognizes that religions are sometimes considered “dangerous,” because they have betrayed the core teachings they espouse, he said.

The new pope singled out interreligious dialogue as a priority on the very first day of his pontificate, the cardinal noted, “and Pope Francis is indeed sensitive to the role of interreligious dialogue in promoting peace.”

But interreligious dialogue was also a priority of previous popes,” Cardinal Tauran reminded me, citing both Benedict VII and Jean Paul II. “They have been not only sensitive to Christian testimony, but also to the necessity of interreligious dialogue for the survival of humanity.”

Interfaith dialogue at the Vatican goes back farther. Pope John XXIII convened the Second Vatican Council (1962-65), one of the most significant events in modern Church history. It resulted in the Church’s ground-breaking public documents on interfaith dialogue, social justice, religious freedom, and religious pluralism.

Cardinal Tauran also referred to October 2011 when the Holy See marked the 25th anniversary of Assisi’s Day of Prayer for Peace. In October 1986 Jean Paul II first convened an assembly of interfaith leaders at the Church of St. Francis of Assisi in Italy to pray together for the first time in history. At the closing Pope John Paul II remarked:

“For the first time in history, we have come together from everywhere, Christian Churches and Ecclesial Communities, and World Religions, in this sacred place dedicated to Saint Francis, to witness before the world, each according to his own conviction, about the transcendent quality of peace. The form and content of our prayers are very different, as we have seen, and there can be no question of reducing them to a kind of common denominator. Yes, in this very difference we have perhaps discovered anew that, regarding the problem of peace and its relation to religious commitment, there is something which binds us together.”

Clarifying the role of the Council, Cardinal Tauran was eager to distinguish between the interfaith work of the Vatican and the work of the individual Catholic churches around the world. “We brainstorm here in Rome – as a coordinating body – but then we encourage the Catholic churches themselves to engage in actual interfaith dialogue.”

2002 Assisi Decalogue for Peace

At the 2002 interfaith prayer service at Assisi, ten of the 200 faith representatives each read one of the following ten commitments in his own language. Later, Pope John Paul II sent a copy of the Decalogue for Peace to all heads of state and, in an accompanying letter, stated that the participants at the Assisi gathering were inspired by one common conviction — humanity must choose between love and hatred.

- We commit ourselves to proclaiming our firm conviction that violence and terrorism are incompatible with the authentic Spirit of religion, and, as we condemn every recourse to violence and war in the name of God or religion, we commit ourselves to doing everything possible to eliminate the root causes of terrorism.

- We commit ourselves to educating people to mutual respect and esteem, in order to help bring about a peaceful and fraternal coexistence between people of different ethnic groups, cultures, and religions.

- We commit ourselves to fostering the culture of dialogue, so that there will be an increase of understanding and mutual trust between individuals and among peoples, for these are the premises of authentic peace.

- We commit ourselves to defending the right of everyone to live a decent life in accordance with their own cultural identity, and to form freely a family of their own.

- We commit ourselves to frank and patient dialogue, refusing to consider our differences as an insurmountable barrier, but recognizing instead that to encounter the diversity of others can become an opportunity for greater reciprocal understanding.

- We commit ourselves to forgiving one another for past and present errors and prejudices, and to supporting one another in a common effort both to overcome selfishness and arrogance, hatred and violence, and to learn from the past that peace without justice is no true peace.

- We commit ourselves to taking the side of the poor and the helpless, to speaking out for those who have no voice and to working effectively to change these situations, out of the conviction that no one can be happy alone.

- We commit ourselves to taking up the cry of those who refuse to be resigned to violence and evil, and we desire to make every effort possible to offer the men and women of our time real hope for justice and peace.

- We commit ourselves to encouraging all efforts to promote friendship between peoples, for we are convinced that, in the absence of solidarity and understanding between peoples, technological progress exposes the word to a growing risk of destruction and death.

- We commit ourselves to urging the leaders of nations to make every effort to create and consolidate, on the national and international levels, a world of solidarity and peace based on justice.

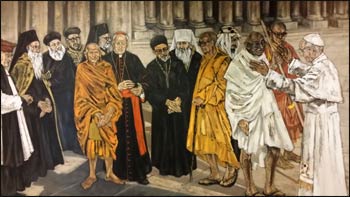

A painting in the Vatican’s interreligious offices

Each director of the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue has brought his unique birthright, character, and experience to the job. Nigerian-born Cardinal Francis Arinze, who headed the Council from 1985-2002, appointed by Jean Paul II, was a religious convert. Arinze’s parents, peasant farmers in rural Nigeria, were followers of an indigenous village religion. When a Catholic mission school opened in their village, Francis’ brother, Christopher, became a student. Soon his seven brothers and sisters all became Catholics. A very studious, devout Catholic,Francis Arinze eventually became Rome’s youngest bishop, at the age of 32.

When Pope John Paul II made a historic rapprochement with Judaism in 1965, Arinze believed it was also the ideal moment to do the same with Islam, according to an article written by BBC reporter David Loyn. The 120 million people in Nigeria, “the most religious country in the world,” according to a BBC poll, were at the time roughly evenly divided between Muslims and Christians. Cardinal Arinze believed that because of Catholics’ adoration of Mary, Catholics could meet Muslims on common ground.

The next to head the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue was Archbishop Michael Fitzgerald, an Englishman, who spoke fluent Arabic and was part of the “White Fathers,” as the missionaries of African were known. Archbishop Fitzgerald, serving from 2002 to 2007, was considered a leading expert on Islam, Muslim-Christian relations, and interreligious dialogue. Fitzgerald was integral to drafting “Dialogue and Proclamation,” concerning the relationship between dialogue and evangelization. From 1972 to 1978 he helped create and publish “Encounter, Documents for Christian-Muslim Understanding,” a periodical, and he supervised the launch of “Islamochristiana,” a scholarly journal dedicated to Muslim-Christian relations and interreligious dialogue.

He viewed Vatican II, in particular the declaration Nostra Aetate (In our Time) on relations with other religions, as the modern impetus for interreligious dialogue in the Catholic Church. For Fitzgerald, the goal of interreligious dialogue was to achieve some sort of theological unity between all religions – not to produce a new world religion which, in truth, even today can make people wary of interfaith dialogue and what they fear may be the outcome of getting too comfortable with one another’s faiths. He also hoped that Christians would not be afraid to express their own convictions. He believed that any semblance of syncretism and relativism ought to be avoided.

As one would expect, the study and appreciation of other religions has been a recurring theme not just for the popes but for the men they appointed who have faithfully chaired the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue. They have taken their cue from the popes they served, and they continue to encourage ecumenical and interfaith engagement on all fronts.

“Life is beautiful when you are trying to unify brothers and sisters,” concluded veteran diplomat Cardinal Tauran with an optimistic smile. “We are all pilgrims toward the truth.”