By Katherine Marshall

UNPACKING THE HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Contemporary reflections about interreligious institutions and practices commonly highlight an ambitious meeting in Chicago in 1893, termed the World’s Parliament of Religions, as a starting point of the modern interfaith movement.

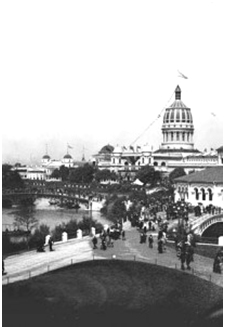

Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, 1893 — site of the World’s Parliament of Religions – Photo: Wikimedia

The 1893 Parliament had a distinctive American context and ethos. It took place during a period when a flood of mostly poor immigrants from southern Europe, including many Jews fleeing Russia, were an important social and political reality. Xenophobia and nativist feelings were on the increase and they inspired laws designed to limit the entry of migrants (the Chinese exclusion act was passed in 1882 and the Immigration Restriction League was established in 1894). New literacy requirements and other measures aimed to keep some immigrants out and to favor northern European, educated populations.

More broadly, this was a period of cultural upheaval, with rapid urbanization, the industrial revolution, and transformations in communications. Europe saw similar cultural upheavals, exacerbated by the long world depression from 1879 through 1896, with repeated stock-market crashes, company collapses, and high unemployment. Mass movements of people in different world regions brought people of different religious traditions into closer daily contact.

In part to contest, nativist politics, a private group of religious leaders organized the Parliament gathering in Chicago (linked to the World’s Fair) to bring together what they saw as world religious leaders. Tensions between cultural opening and cultural narrowing affected who did and did not attend the Parliament. The very idea perturbed some established leaders: Pope Leo XIII censored Catholics who attended such “promiscuous events,” and the Archbishop of Canterbury refused to bless it. The Parliament itself was Christian-centric with a strong undercurrent of evangelization directed at the other religious leaders.

Despite tensions and undercurrents, the Parliament opened new windows to many Americans about the wide array of world religions, and that captured imaginations. It brought together leading voices in the emerging religious studies field with theologians and religious leaders. Several leaders, including Swami Vivekananda, gained stature and propounded their messages of harmony in various forms in the following years.

Various interreligious initiatives came in the immediate aftermath of the 1893 Parliament. Some survived while others vanished. In the ensuing decades there was, however, no obvious focal point or sense of direction for interreligious cooperation. It was not a priority of the era.

Most interreligious efforts through the post-World War II period can be seen as individual, highly localized, and focused on educating others about religious diversity. Interfaith and interreligious understanding was much influenced by academic developments, though collaboration between individual religious leaders and communities, especially around labor rights and emerging social responses to urban poverty, brought groups together. Long-standing, traditional patterns of parochial thinking were challenged, at least among various elites, by more cosmopolitan notions that included tolerance of different worldviews, including religious beliefs. Three enduring global interreligious organizations were born during this period: the International Association for Religious Freedom (established in 1900), the World Congress of Faiths (established in 1936), and the World Council of Churches (incorporation voted in 1937, formally established in 1948). They reflect three emerging threads of the interfaith movement: protection of religious rights, pragmatic collaboration, and conscious efforts to bridge divides of understanding.

During the Cold War years (1945-1989), a secular paradigm tended to dominate many approaches to international relations in the United States, to a degree that actors were in many respects blinded to the enduring power of religion. The common assumption was that, with modernization, religious institutions and practices were less important than in the past; religious matters were to remain in the private sphere with a sharp separation of church and state. Several important interreligious institutions grew nonetheless, but to a large extent they operated at that time on the fringes of formal international relations. The most significant example was the World Conference on Religion and Peace (today Religions for Peace), created in 1970, but formed over an extended period through smaller gatherings in the 1960s that focused largely on a multireligious call for nuclear disarmament. A repurposing and expansion of Religions for Peace in the early 1990s saw it making some pioneering steps towards cooperation (formal and informal) between interreligious actors and governments and intergovernmental agencies.

The era saw initiatives that were often propelled by the passion and financial resources of remarkable individuals. An example was the Temple of Understanding, established by Juliet Hollister, an ideal that Life Magazine described in 1962 as her “magnificent obsession.” It had the blessing of Eleanor Roosevelt and envisaged a place and institution that would be a spiritual United Nations. The Temple of Understanding, in a different (smaller) form persists to this day, focused on peace education. The United Religions Initiative (URI) was born in 1993, also largely inspired by a dynamic individual, Episcopal Bishop William Swing. Its name was a deliberate parallel to the United Nations, and its ethos has been much influenced by a grassroots notion of organization, participation, and broad inclusion. URI is based today in San Francisco and has evolved into a global organization grounded in what it terms cooperation circles. Its methodology and philosophy were much influenced by the appreciative inquiry approach of David Cooperrider.

The 1960s and ‘70s saw the explosive increase of civil society organizations and their growing roles in many sectors and world regions. Many such organizations were religious in inspiration (Catholic Relief Services and Islamic Relief among them) and they had a marked influence on the way in which religious contributions to society were viewed. They also engaged in practical ways with different organizations. Another dimension of the civil society revolution was widely varying and increasing interfaith work at local levels, though it is in general poorly mapped in any aggregate form. Civil society and community-based dynamics, together, laid foundations that encouraged or supported religious actors as they took on new forms of engagement and advocacy, notably work for the environment, poverty alleviation, and peace. Many efforts tapped into, or were born out of, tight networks of religious communities and new spiritual movements. Many political parties and movements had roots in religious institutions and beliefs.

Interreligious activists during this period tended to be torn between models that implicitly favored predominantly top-down approaches (a rather traditional religious model). Other favored more self-consciously “bottom-up” or grassroots models. Various influential people power movements had religious pedigrees, notably liberation theology in Latin America, the civil rights movements in Northern Ireland and the U.S., the Carnation revolution (Portugal 1974), the Singing revolution (Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania 1988) and the Velvet revolution (Czechoslovakia 1989). Religions for Peace (RfP) was shaped by these developments as it struggled to find a middle ground between formal religious leadership and a more community grounded approach.

Pope John XXIII was responsible for calling together Vatican II, though he died before the conclave concluded. – Photo: Wikimedia

The Catholic Church engagement with other religious traditions merits exploration far beyond the scope of this reflection, because of its depth, global reach, and elaborate intellectual contributions. The early 1960s saw a change in Catholic Church approaches to relationships with other religious bodies that had profound implications both for Catholic communities and beyond. The Second Vatican Council, the twenty-first ecumenical council and the second held at the Vatican, opened in 1962 and closed in 1965 with sweeping agreements on change that amounted to a revolutionary opening up. Besides changes in liturgical practices, encouragement of lay leadership, and decrees on ecumenism, the Council approved Nostra Aetate, a declaration on the relation of the Church to non-Christian religions.

The document, whose fiftieth anniversary is celebrated in 2015, is credited with stimulating many ecumenical and interfaith studies and gave energy to interfaith initiatives in the 1960s and beyond. Reflecting consultation with Jewish, Muslim, and Christian (Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant) leaders, it states that the Church accepts some truths inherent in other religions as reflections of Catholic teaching. It also includes a formal resolution to stop blaming Jews for the death of Jesus, previously enshrined in church liturgy. Most importantly, Nostra Aetate set in motion a chain reaction whereby religious communities developed and institutionalized approaches to the religious “other.” These have had profound structural impacts on the development of interfaith work and institutions.

As the one hundredth anniversary of the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions approached, the post-Cold War era was taking shape, transforming international politics swiftly and dramatically. Globalization was a much discussed phenomenon but also one that shaped daily lives in tangible ways: development of the Internet and the personal computer, for example, was increasing connectivity in ways few people could have imagined only a few years earlier. It was in this context that plans took shape to hold a newly named Parliament of the World’s Religions, also in Chicago, in 1993, 100 years after its pioneering predecessor.

Professor Diana Eck of the Pluralism Project at Harvard University greets Dadi Prakashmani of the Brahma Kumaris at the 1993 Parliament. – Photo: CPWR

The 1993 Parliament was organized by the Council for a Parliament of the World's Religions (CPWR), incorporated in Chicago in 1988. Daniel Gomez-Ibanez served as chair of the CPWR board of trustees and then as executive director of the Parliament event itself. Thus an ad-hoc interfaith group, established for the purpose, took charge. It arose from informal beginnings in Chicago’s Hindu, Buddhist, Bahai, and Muslim communities and was supported by the Council of Religious Leaders of Greater Chicago. The group aimed at large attendance and high visibility, and they succeeded: some 8,000 people attended and Chicago Mayor Richard Daley served as Honorary Chairman. The Dalai Lama was a distinguished guest (Mother Teresa had planned to attend but canceled at the last minute because of illness). Two very public conflicts added drama: three Jewish organizations objected to the participation of the Nation of Islam, and some Orthodox church leaders withdrew, unwilling to participate with non-theists.

The 1993 Parliament, nonetheless, symbolized a common and public emphasis on the positive contributions that religious communities could bring and suggested that far more could be achieved together than separately. The Parliament featured prominently a call for a global ethic, promoted by Swiss theologian Hans Küng and others. This ethic emphasized common teachings that united different faith traditions in a tangible way. Several public gatherings at the Parliament centered on signing the aspirational Towards a Global Ethic – An Initial Declaration.

In sum, the 1893 Parliament of Religions might be seen in retrospect as largely a response to intellectual and religious curiosity to religious diversity. A century later the challenge for the 1993 Parliament was fundamentally different with far higher stakes.

In sum, the 1893 Parliament of Religions might be seen in retrospect as largely a response to intellectual and religious curiosity to religious diversity. A century later the challenge for the 1993 Parliament was fundamentally different with far higher stakes. These have risen higher still in the ensuing decades as religious wars with markedly religious elements, inter and intra religious tensions, and the rise of violent extremism have shaken both national and international affairs. The challenges of plural societies and the complex roles of religion in daily lives, in social cohesion of communities, of national politics, and international relations have taken on new dimensions. Interreligious cooperation has come to be seen as fundamental to peace, human security, and prosperity in the increasingly complex and often fractious world.

This article is excerpted from a history of the interfaith movement to be published next year. Cassandra Lawrence provided substantial input to the review. The article is slightly revised from an earlier version with additional detail.