When Heresy Meant Death

Michael Servetus – the Martyred Interfaith Prophet

by Marcus Braybrooke

Michael Servetus, who wrote for Jews and Muslims as well as Christians, has been called by Jerome Friedman, “a prophet of interfaith dialogue.” He was a man of prodigious intellect, a scientist and a free-thinking theologian. Servetus is credited with the discovery of pulmonary circulation in the human body. He has been hailed as the first Unitarian and labelled a “total heretic” – burned in effigy by the Catholic Church, and physically burned to death on Calvin’s orders in Geneva in 1553 at the age of 42. Servetus anticipated many of the questions discussed by critical Christian scholars over the past 150 years.

This etching was created by Christian Fritzsch in the 18th century, more than a hundred years after Servetus’ execution, which dominates the upper left of the portrait. – Photo: Wikimedia

Michael Servetus, Miguel Serveto in his homeland, was born in southern Spain in 1511. Twenty years earlier Columbus had set sail for the New World. Of more importance to Servetus, the old Moorish kingdom of Granada had been conquered by the ardent Christian rulers King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, and the Edict of Expulsion was signed in Granada. As a result, 200,000 Jews left Spain. Those who converted – so called ‘Marranos’ – were hounded by the Inquisition. Servetus’ mother’s family may have been converses, as the converted were also called.

Servetus had a good education and became proficient in Latin and Greek. He also learned Hebrew. At the time this was an unusual and dangerous thing to do. In most of Europe, Hebrew was a forbidden language because the Old Testament could only be read in translations approved by the Church. It had, therefore, to be learned in secret. Probably, at some stage he learned Arabic. Servetus certainly read the Qur’an and referred to the first Latin translation, which was printed in 1543, and may earlier have used a manuscript Latin translation or read the Qur’an for himself.

As a teenager, Servetus went to Zaragossa University. He then became personal secretary to Juan de Quintana, an important Franciscan friar, who had been influenced by Erasmus. Quintana encouraged Servetus to read the whole Bible in Hebrew and Greek manuscripts. In 1529-30, he traveled with Quintana to Rome, where he was shocked by the worldly pomp of the papacy. Leaving his patron, Servetus met with leaders of the Reformation, including Martin Bucer (1491-1551) and Johannes Oecolampadius (1482-1531), with whom he stayed in Basel for some time. Their disagreements about the Trinity became so bad that they stopped talking to each other and only communicated by letter.

Learning that Oecolampadius was about to denounce him publicly, Servetus left for Strasbourg. In July 1531 Servetus published his controversial De Trintatis Erroribus (“On the Errors of the Trinity”) and in the following year his De Justitia Regni Christi (“On the Justice of Christ’s Reign”). He denounced the doctrine of the Trinity as “inconceivable” and “madness,” adding that “worst of all it incurs the ridicule of the Mohammedans and the Jews.”

To avoid persecution because of his radical views, Servetus adopted the name of Michel de Villeneuve or Villovanus. He found work as an editor of scientific books and published an annotated translation of the Geographia by the second century geographer and astronomer Ptolemy. He then studied medicine at Paris and matriculated in 1538. In a later work, he was to be the first European to describe the circulation of blood in the human body.

Following his studies at Paris, Servetus, as we will continue to call him, practiced medicine near Lyons in France for some 15 years, becoming the personal physician to the Archbishop of Vienne. He continued to write books about medicine and edited, with notes, an edition of Biblia Sacra ex Santis Paginini translatione (Holy Bible according to the translation of Santes Pagnino, 1542).

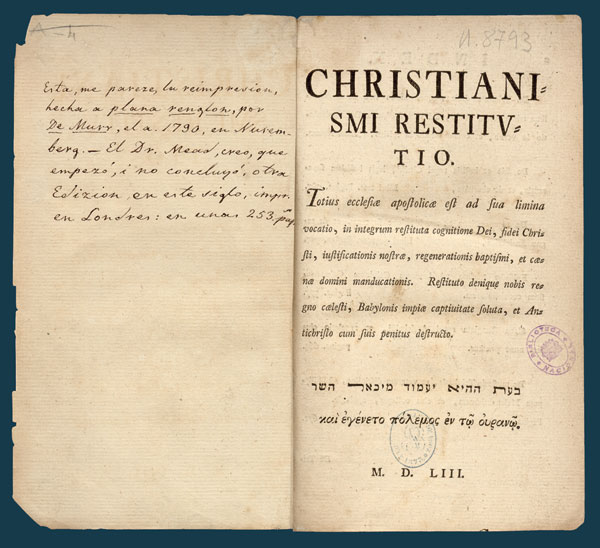

Christianismi Restitutio – Photo: Skinner House Books

In 1553 Servetus published Christianismi Restitutio (“The Restoration of Christianity”), which he had worked on secretly for eight years. The book has nearly 800 pages, with detailed references to support his arguments. He denounced infant baptism, partly because he thought children under twenty were not capable of mortal sins and because he rejected the doctrine of original sin, “which depravity of our nature,” in Calvin’s words, was inherited from our parents. He pointed out that Jesus had told his followers “to be perfect, as your Father in heaven is perfect.” (Matthew 5.48).

Even more controversial was his rejection of the doctrine of the Trinity, which he said has no basis in the Bible. Instead of speaking of One God in Three Persons, Servetus stressed the unity of God. He saw Father, Son, and Holy Spirit as modes of operation rather than distinct entities. God is seen by humans to relate to the world as Creator, Savior, and Inspirer. But the Godhead’s inner being is unknowable by humans – as many mystics have also said. For Servetus, the eternal Word, which was conjoined with the human Jesus, was a phase of God’s activity, not a separate person in the Godhead. Likewise the Holy Spirit is God’s spirit moving in our hearts.

Servetus has been claimed as an early Unitarian. But the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biographies says, correctly I think:

Sharply critical though he was of the orthodox formulation of the Trinity, Servetus is better described as a highly unorthodox Trinitarian. Still, aspects of his thinking – his critique of existing Trinitarian theology, his devaluation of the doctrine of original sin, and his fresh examination of biblical proof-texts – did influence those who later inspired or founded Unitarian churches in Poland and Transylvania.

Servetus’ position receives some support in contemporary theological debate. A number of modern Christian scholars agree that in the New Testament, there is no explicit Trinitarian statement and that it is questionable also whether Jesus is ever spoken of just as God. The creeds, which define the doctrine of the Trinity, date to the fourth century and reflect Greek rather than Hebrew thinking.

These disputes may seem very abstruse; but how Christians understand the doctrine of the Trinity and the Divinity of Christ, may affect whether they recognize God’s presence in other faith traditions. The influential Protestant theologian Paul Tillich (1886-1965), distinguished the human ‘Jesus of Nazareth’ from ‘Jesus as the Christ’ – meaning by Christ the principle of New Being or Divine Logos or Word. I personally prefer to say ‘God was in Christ Jesus’ rather than ‘Jesus is God.’

Calvin and Servetus – a painting by Cuadro de Theodor Pixis (1831-1907) – Photo: Miguel Servet

In the sixteenth century such questioning was seen as a threat to the whole edifice of Christendom. Charges were brought against Servetus, and he was arrested and imprisoned by the Catholic authorities in Vienne. He escaped just before he was condemned, but his effigy and his books were burned in his absence.

His real antagonist was John Calvin (1509-64), who had made Geneva the center of the Protestant Reformation. Servetus and Calvin had known each other for some years and their correspondence was increasingly vitriolic.

Intending to find refuge in Italy, Servetus, inexplicably, stopped in Geneva, and rashly, went to hear a sermon by Calvin. He was recognized and arrested as soon as the service finished. Servetus was put on trial, with Calvin leading the attack. Servetus wrote to the Council urging them to “shorten the deliberations.” “It is clear”, he wrote, “Calvin for his pleasure wishes to make me rot in this prison. The lice eat me alive. My clothes are torn and I have nothing for a change, no shirt, only a worn out vest.” The trial resulted in Servetus’ condemnation.

As Servetus was not a citizen of Geneva, legally the harshest penalty should have been banishment, but instead on October 27, 1553 Servetus, with his book chained to his leg, was burned as a heretic. To prolong his agony, new wood was used that took longer to burn. A few voices, however, were raised against imposing the death penalty for heresy, and Servetus’ execution damaged Calvin’s reputation at the time and subsequently. Servetus’ last words were, “Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have mercy on me.”

Calvin then instructed the printer to hunt for and destroy any remaining copies of Christianismi Restitutio. Yet in what is an amazing story, so well told by Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone’s Out of the Flames (2003), three copies survived.

Although the theological arguments are still significant, Servetus is best remembered as a martyr for freedom of thought and liberty of conscience. This certainly is how both Voltaire (1694-1778) and Thomas Jefferson saw him. The author August Dide said at the dedication of his statue, “Glorifying Servetus … we honor what is the most precious and most noble in our human nature: a generosity of heart, independence of the spirit, and heroism of convictions.”

Sadly holy hatred and cruelty in the name of God are still with us. May Servetus’ example encourage us to challenge falsehood and prejudice.

Header Photo: Geneva by D. Danckerts , c. 1660. – Photo: Sanderus Antiquariaat