By Marcus Braybrooke

KEY FIGURES IN INTERFAITH HISTORY

Vivekananda’s fame, exemplified by this stature of him at the Hindu Temple of Chicago, has overshadowed the important contribution of other Asian leaders at the 1893 Parliament.

Some Jain friends at the 1993 Parliament of World Religions gave me a booklet with the title We Were There As Well. Too easily the starring role of Swami Vivekananda has obscured the significant contribution that other Asian participants made a hundred years earlier at the 1893 World Parliament of Religions, participants who deserve to be remembered.

Jains indeed knew about and participated at the historic 1893 Chicago gathering. The High Priest of the Jain community in Bombay, unable to attend, described the Parliament as “The dream of my life.” Virchand A. Gandhi, a Jain lawyer from Bombay who did attend, spoke at both opening and concluding ceremonies. On another occasion Virchand Gandhi expressed his sadness that some missionaries had attacked Indian religions,whereas the abuses in Indian society “are not from religion but in spite of religion, as in every other country.”

Protap Chunder Mozoomdar

The Brahmo-Samaj, a Hindu reform movement, was represented by Protap Chunder Mozoomdar and B. B. Nagarkar. Mozoomdar was already known to some Americans through his book The Oriental Christ, published in Boston in 1883. Mozoomdar claimed that the Western picture of Jesus was distorted. Jesus was an Asian with whom Asians had a natural affinity. The Theosophical Society, which had been founded in New York in 1875 before moving itsheadquarters to India in 1882, was represented by C.N Chakravarti, who spoke at the opening session.

A paper on Zoroastrianism by the eminent scholar Sir Ervad Jivanji Jamshedji Modi was read by Jeanne Sorabji, whose father was a Zoroastrian, although she herself had converted to Christianity.

The two men in the middle, Anagarika Dharmapala, in white, and Swami Vivekananda, in the turban, share the platform with other dignitaries at the 1893 Parliament.

Six Buddhists attended the Parliament. The best known, perhaps, is Srimath Anagarika Dharmapala, one of the most influential Buddhists of modern times. Two years before the Parliament, he and Sir Edwin Arnold, well-known for his poem “The Light of Asia,” founded what became known as the Maha Bodhi Society in Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Dharmapala stayed on after the Parliament to lecture in America, where he founded a branch of the Maha Bodhi Society.

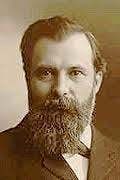

Shaku Soyen

Shaku Soyen, a well-known scholar and head of the Engakuji division of the Rinzai Zen Buddhism, attended and subsequently introduced D.T. Suzuki to the West. Back in Japan he organized to “Little Parliaments” in 1896 and 1897. In 1993, while participating in a Japanese celebration marking the centenary of the Parliament, I was shown the medal that Shaku Soyen had been given in 1893.

Other Buddhists who traveled to Chicago back then included the King of Siam’s brother, who presented a paper; Zitsuzen Ashitsu of the Tendai school, founder of the Meido Society for spreading Buddhism; Kinza Riuge M. Hiral, who spoke on “Synthetic Religion”; and two Japanese Buddhist bishops, Horiu Toki and Banriu Yatsubuchi. They were accompanied by Zenshiro Noguchi, who translated for them.

Paul Carus, a distinguished author and publisher and a pioneering thinker about science and religion, was deeply moved by Asian contributions to the Parliament, particularly the Buddhists. In 1894 he published The Gospel of the Buddha, filled with sayings and parables about Buddha, which was reprinted many times.

Paul Carus

Shintoism was represented by Reuchi Shibata, who prayed that the eight million deities protecting the beautiful cherry tree country of Japan would also protect the people of America. The Emperor of China had responded warmly to the initial invitation and sent the First Secretary of the Chinese Legation, Pung Kwang Yu, to represent him.

The greatest disappointment was the virtual absence of Muslims, largely because the Sultan of Turkey opposed the event and would not allow Muslims from his empire to attend. Justice Ameer Ali of the Supreme Court of Calcutta, who had hoped to attend but could not, described the Parliament as “the greatest achievement of the century.”

Two Muslims who did come from India, Jinda Ram and Siddhu Ram, were on the platform for the opening ceremony. The only Muslim to speak was an American convert, Alexander Russell Web of New York. His initial remarks about polygamy were greeted with cries of shame – the only vocal protest during the whole seventeen days. His subsequent remarks, the editor of the proceedings said, were heard “with patient attention.”

Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb, a convert to Islam.

Although Matthew Arnold had made fleeting reference to the Baha’i’ faith as early as 1871, it is often said that the first mention in the West of the Baha’i’ faith was at the Parliament when Henry Jessup, from Beirut, ended his address by quoting words of its founder, Bahá'u'lláh, that all “all nations should become one in faith… Let not a man glory in this, that he loves his country; let him rather glory in this, that he loves his kind.”

I can find no mention of Sikhism in the records of the Parliament.

Recalling the names of participants from Asia brings the Parliament to life because it is always people who meet not ‘religions.’ Equally important, it counteracts the impression sometimes given that the 1893 Parliament was just a gathering of liberal Protestant Christians, even if they were the majority in the audience.

The inference also ignores the significant contribution of Roman Catholics and Jews, which is another story. It bears noting that the Asian participants were given a high profile and seated on the platform at the opening and closing ceremonies. Most gave more than one address, and their colorful robes made them stand out.

Henry Barrows, organizer of the Parliament, would have liked a bigger representation from overseas. But the small number who came, whose words were widely reported in the press, changed many people’s perceptions. Questions began to be raised about missionary work and the traditional exclusive claims of Christianity. Asia had begun to export its religions to the West. Hindu and Buddhist centers were soon established in America, books on world religions were published, and more people began to study comparative religion.

Sadly, the high hopes and the friendships made in 1893 could not prevent the cruel bloodshed of the twentieth century: but the dream lives on, and we can still find inspiration in the words and lives of those who attended the first World Parliament of Religions.