Religious Conservatives and Interfaith Dialogue

by Wm. Andrew Schwartz

As readers of the Interfaith Observer know full well, the world is in the midst of an unparalleled religious diversity. Everyone acknowledges this new reality. The ways we respond are legion. Historically, progressive religious adherents are most likely to identify as religious pluralists and work intentionally to develop new friendships with religious strangers.

More conservative religious adherents often have a different perspective on religious diversity. An important aspect of Conservatism is “conserving” the tradition which feels threatened by the diversity of voices both within and beyond the boundaries of one’s community. I grew in a religiously diverse household (a Jewish father and Christian mother), but I was raised, educated, and licensed in a moderately conservative Evangelical Christian denomination – the Church of the Nazarene.

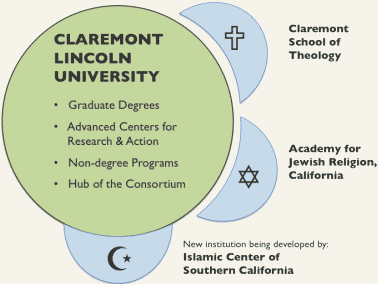

Today, though, I find myself in Claremont, California, the old stompin’ grounds of pioneering interfaith theologians like John Hick and John Cobb. My doctoral program in the Philosophy of Religion focuses on religious pluralism and comparative philosophy, religion, and theology. Even worse in some eyes, I suppose – I work at the Center for Process Studies, a faculty research center of Claremont Lincoln University, which has been called the world’s first interreligious university.

How exactly did an Evangelical Christian end up on the growing edge of interfaith cooperation? Have I been lost? Or found?

At a young age, deciding that God is the most important priority, I devoted my life and career to God’s service. For me, that meant becoming a pastor. I went to Northwest Nazarene University and studied religion with a focus in Pastoral Ministry. Early on I added a second major, Missions, with an emphasis in cross-cultural orientation. Mission trips, including a summer in Kosovo as a short-term missionary, woke me to the joy of traveling to other countries and seeing their ways of life. I expected to become a missionary, taking the good news of a loving God and salvation through Jesus Christ to a remote area of the world.

Digging Deeper

Over time, my encounters with good people from other faiths sparked a personal quest for a deeper understanding of Christian salvation, including doctrines of atonement and of God. Enveloping myself in these studies, each answer led to more questions. In short, I discovered that Christian theology is not singular! It is dynamic, extremely diverse and complex. This diversity and complexity in my own tradition encouraged me to question the absolutist and exclusive claims I held so deeply.

Diversity within Christianity quickly led me to ask about diversity beyond Christianity, and I began to explore the multiplicity of perspectives offered by a number of different faiths. In the process, my ingrained attitude of suspicion toward other religions became an attitude of wonder.

John Hick

Rather than alienating me from my faith, my new openness and my tradition became interwoven. I continued at the Nazarene seminary. I worked at the International Headquarters of the Church of the Nazarene. At the same time, I worked diligently on issues like absolutism and religious pluralism, discovering the work John Hick in the process. My MA thesis explored the possibility of adopting Hick’s pluralistic hypothesis as a possible Wesleyan perspective.

Needless to say, there were those in my church who were concerned about my project.

The Church of the Nazarene is a Wesleyan-Holiness denomination, inspired by the theological heritage of John Wesley and influenced by both Methodism and the American Holiness Movement. Broadly speaking, it can be identified as part of American Evangelicalism. Nazarenes affirm the divine inspiration of the Bible and salvation through Jesus Christ. Our most characteristic doctrine is the doctrine of holiness, connected to our concern for the poor and oppressed.

John Wesley

Like all evangelical churches, salvation is a central concern. As such, it is no surprise that Nazarene engagement with those of other faiths is generally in the form of conversion attempts rather than conversation or cooperation.Does this mean that interfaith cooperation is impossible for religious conservatives, including the Church of the Nazarene? Not at all.

As a means of preserving my commitment to the Church of the Nazarene while honoring my intellectual, personal assent to the value of non-Christian religions, interfaith dialogue and comparative theology have been priceless.

The practice of comparative theology does not require the rejection of one’s faith. Quite the contrary, comparative theology, from my Christian perspective, is like all Christian theology – a matter of faith seeking understanding. In the case of comparative theology, the “seeking” is done across religious borders, beyond one’s own faith tradition. It is from within a strong commitment to my own faith tradition that I, as a Wesleyan-Holiness theologian, can explore and embrace the perspectives of other religious traditions. Comparative theology garners value from each participating faith perspective. Nazarenes can provide new contributions to the discipline of comparative theology even as we gain learnings new to us from other traditions.

Similarly, interreligious/interfaith dialogue means retaining a commitment to your own tradition while remaining open to the beliefs, practices, and experience of others. In interreligious dialogue, people from two or more faiths come together to communicate. Unlike casual conversation and information sharing, this dialogue involves speaking from the heart, sharing important stories, and listening and being deeply listened to by someone recently a stranger. When this happens mutual transformation, growth in who we are as human beings, is wondrous and easy. A deeper give and take is served, grounded in vulnerability, honesty, and openness.

There is nothing here to keep a religious conservative at bay. There is no conflict between the integrity of your faith and being open, respectful, and engaging with those from different faiths. You can remain true to their own faith while having constructive encounters with those who practice other traditions, particularly when you exchange stories about what is most important to you about faith and practice.

Andrew standing in front of the Nazarene Global Ministry Center

The question for some is, Why should we seek to encounter religious ‘others’ this way? After all, searching “beyond one’s own faith tradition” or contemplating “mutual transformation” are notions that unnerve many Christians. Scary? Sure. It takes courage to say yes to anything new, like exchanging personal faith stories with a person from a different religion, say a Muslim or a Hindu. The expectation inspires foreboding, but the realization can quickly become enriching and deeplysatisfying, adding not subtracting from the meaning of your life. The risk is absolutely worth the reward.

From a Nazarene perspective, God is always at work in the world. As finite creatures, we certainly haven’t unraveled the mystery that is God. To Christians, God, who created the heavens and the Earth, is by no means contained within the limits of the Christian religion.

So engagement with other religions can be act of spiritual formation in which we experience God in new ways, at work in the world and the lives of others.In my experience, this level of sharing and dialogue has enhanced and enriched my Christian faith. I am a better Christian today because I’ve studied Jainism, Buddhism, Islam, and others. I’m not sure I would say, in the spirit of Paul Knitter, that “Without Buddha I Could Not Be a Christian.” But I do believe that because of my encounters with non-Christian persons I have a deeper sense of my Christian faith and a stronger awareness of my identity as a Nazarene.