By Paul Chaffee

From Faith to Interfaith

Most of the several hundred seminary campuses crisscrossing Canada and the United States were developed by individual religious traditions. They wanted to ensure a steady, dependable source of new leaders for their denomination’s congregations. Over the decades most of these seminaries developed similar curricula – ancient languages, scripture, history, theology, ethics, pastoral care, and the liturgy, policies, and history of each school’s particular tradition. This shared curriculum, though, did little to connect the different traditions to each other. In most of these schools, memory, vision, values, and institutional structures all come through the lens of a particular tradition.

Little time was left in such an education to relate to others or their traditions. For Christians, ecumenism provided one way to engage in a larger religious community than just one’s own. But for the most part, seminaries and the traditions they serve have been denominational silos.

That reputation endures to this day, but it no longer tells the truth. New affiliations and partnerships dot the academic landscape, connecting all sorts of traditions in various ways. Graduate Theological Union (GTU) in Berkeley includes one of the largest religious libraries in the country, nine seminaries, and 11 religion-related academic centers, all cross-registered with University of California (Berkeley). At one of those nine seminaries, the Unitarian Universalist Starr King School for the Ministry, Dr. Ibrahim Farajaje is provost and vice president of Academic Affairs; he is also the imam of a local mosque. GTU is awash in interfaith opportunities and is initiating a new Master of Arts program in Interreligious Studies this fall. GTU is not unique. Similar cross-fertilization is going on Chicago, Toronto, Boston, New York, and elsewhere around the world.

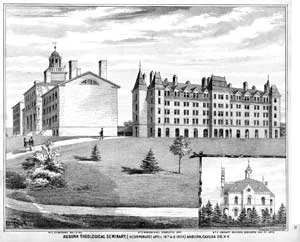

Auburn Theological School was founded in 1818 to train Presbyterian ministers. Today its leadership training welcomes all traditions.

Two and a half years ago Auburn Theological Seminary released a report titled “Multifaith Education in Seminaries.” Their study polled 150 schools of higher religious education, that is, over half the accredited seminaries in Canada and the U.S. They included Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, and multi-religious institutions. These 150 schools, collectively, were offering 1,210 academic courses about “other” faiths. Luther Seminary in Minnesota offers 43 such courses, the most of any seminary. (The study did not include the unaccredited interfaith seminaries profiled elsewhere in this issue.)

Only 14 percent of the 1,210 courses were “world religions” surveys; it seems to be assumed that you’ll have read Huston Smith’s World Religions by the time you get to graduate school. Most of the seminary courses studied different religions from a theological perspective. Seminaries offered three rationales for all this new attention, according to the Auburn study. Multifaith education (1) makes better religious leaders, (2) strengthens faith, and (3) enhances proselytizing.

They also pointed to a number of notable interfaith courses in seminaries. Among the most interesting:

- Meadville Lombard Theological School tackled “Ethical Wisdom: a Comparative Study of Buddhist, Native American, African American, and Humanist Traditions.”

- Pacific School of Religion featured “American Buddhisms: An Experiential Introduction,” allowing students to learn from the experience of different kinds of Buddhist practice.

- “Fundamentalism, Comparatively Speaking,” at Austin Presbyterian Seminary, studied fundamentalist tendencies in Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Judaism, and other traditions.

Interreligious Studies Become an Accreditation Issue

Four years ago, the accrediting commission of the Association of Theological Schools (ATS) began a comprehensive program on multifaith education with its 250 member Christian seminaries and graduate schools of religion. In a series of decisions culminating this past summer, the ATS accreditation requirements for Master of Divinity degrees, as of June 2013, include the following stipulation:

A.2.3.2 MDiv education shall engage students with the global character of the church as well as ministry in the multifaith and multicultural context of contemporary society. This should include attention to the wide diversity of religious traditions present in potential ministry settings, as well as expressions of social justice and respect congruent with the institution’s mission and purpose.

How that happens is each seminary’s business. But Stephen Graham, who led the study, estimates that “two-thirds of ATS member institutions probably meet this requirement already.” He says ATS recently oversaw $5,000 grants to 18 seminaries to create courses focused on Christian hospitality and pastoral practices in a multifaith society. Offerings ranged from “Caring Hospitality in Multifaith Situations” to “Teaching Religion, Conflict, and Peace-Building in a Multifaith World.”

In Front of the Pack

The American Academy of Religions annual meeting late in 2011 featured more multifaith/ interreligious offerings and workshops than ever before. New panels brought together interfaith pioneers who have been at this work for a generation and more. Conferees heard about projects germinating in dozens of seminaries and schools of religion.

A handful of institutions stand out as institutional ‘first-adapters,’ schools imaginative and brave enough to be among the first to teach new ways to turn strangers, even ‘enemies,’ into friends.

Hartford Seminary, in Connecticut, has been a forerunner with the goal of “faithful living in a pluralistic and multi-faith environment.” Hartford’s Duncan Black Macdonald Center for the Study of Islam and Christian-Muslim Religions was founded in 1893, the nation’s earliest such center, and is still vital. Hartford’s programs include a degree in Islamic chaplaincy, pedagogies for interfaith dialogue, and an interfaith Women’s Leadership Institute.

Auburn Theological Seminary offers a variety of interfaith programs in making the claim that “Auburn equips bold and resilient leaders who can bridge religious divides, build community, pursue justice, and heal the world.” They do not have a Masters of Divinity program, but they co-sponsor New York Theological Seminary’s Doctor of Ministry with a multifaith emphasis. An international interfaith project focuses on teenagers. In 2011 Auburn launched its multifaith movement for social justice, called Groundswell, which works with religious communities of all faiths to take coordinated action on issues like racial profiling, LGBT equality, and commercial sex exploitation of children.

Harvard Divinity School’s faculty is robustly interfaith, and Sikhs, Buddhists, Hindus, and others have joined the Christians pursuing a Masters of Divinity. And Harvard is home of the Pluralism Project, the most important repository of interfaith, interreligious information on the internet.

CIRCLE, sponsored by Andover Newton and Hebrew College, provides Christians and Jews a safe, creative environment for sharing their theological education.

Institutions partnering across faith boundaries provide some of the most productive academic interfaith projects. Andover Newton Theological Seminary and Hebrew College share a campus, their students study together, and they co-sponsor the Center for Interreligious and Communal Leadership Education (CIRCLE); the Jewish school and the Christian school each have their own website promoting the Center. CIRCLE hosted a major conference on inter-religion in seminaries and graduate schools of religion in 2010. And it serves as an institutional home for two of the most dynamic interfaith presences on the internet, the Journal of Inter-Religious Dialogue and State of Formation.

Among rabbinical schools, Reconstructionist Rabbinical College has an especially good reputation for its experientially grounded requirements of knowing the ‘religious other.’ At Naropa University, mostly Buddhist students have courses in Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, Islam, and comparative religion. The California Institute of Integral Studies, founded by a Hindu, has established the Chaudhuri Center for Contemplative Practice, Interreligious Dialogue, and Social Justice.

Lest one think that Evangelical Christians are absent, Fuller Seminary, whose 4,000+ students from 100 Christian denominational affiliations make it one of the world’s largest theological schools, offers 13 courses related to Islam, an emphasis in world religion and the arts, and various interfaith dialogue projects. Fuller has particularly attended to ongoing Evangelical-Mormon and Christian-Muslim dialogue and relationship building.

A new Jain Studies program was initiated with candle lighting at Claremont Lincoln University the day CLU first opened its doors, an immediate sign that its commitment to Abrahamic faiths would not overshadow its engagement with other traditions.

The most interesting recent development in higher religious education was the formation of Claremont Lincoln University (CLU) a year ago, enabled by the generosity of Joan and David Lincoln in southern California. (See the report in TIO.) CLU is the first ATS accredited university to offer Christian, Jewish, and Muslim clergy training. It has Jain and Hindu programs, along with a raft of other imaginative options for pursuing interfaith higher education. Its newest program is an interfaith chaplaincy degree.

These remarkable achievements should not overshadow imaginative new programs in religious, spiritual academies everywhere. In Auburn’s study of 150 seminaries, they identified 20 with the most dynamic programs, from the researchers’ perspective. It’s an excellent list for anyone wanting to go to seminary with a strong interfaith emphasis.

This new embrace of interreligious studies in higher education is a source of hope in a world where religion all too often is misused and blamed for inciting conflict. For decades interfaith activists have waited for religion in America to better acknowledge and interact respectfully, collaboratively, with the religions that have come to these shores, generation after generation. That is starting to happen in the halls of academe.