By Rev. Heng Sure

RENEWED COMMUNITY FROM ANCIENT SEED

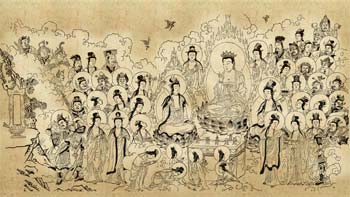

An assembly reciting the Avatamsaka Sutra

I’m sitting in a retreat bungalow in the Australian bush south of Brisbane, near Mudgeeraba, Queensland. I am translating an ancient Buddhist scripture with twenty other people, most of whom are in different countries.

I’m working with a Macintosh laptop facilitating a wireless Skype conference call. I have as well an iPad 2 running FaceTime, Apple’s videophone software, connected to a room in a Buddhist monastery in California. My word processor, Nisus Writer, has a bilingual Chinese-English edition of the Avatamsaka Sutra, that is, The Buddha’s Flower Garland Scripture. The text is said to be the first teaching the Buddha delivered after his enlightenment beneath the Bodhi tree, some 2500 years ago.

The local broadband provider here in Australia’s Gold Coast has extended its coverage out to the bush, Australian for forest. So, via FaceTime, I can see a room with Buddhist monks, nuns, laymen, laywomen, and student interns in Ukiah, California, at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. They in turn see my image projected onto a movie screen in their translation room.

The main gate into the City of 10,000 Buddhas in northern California.

Joining us remotely online via Skype are translators and auditors in Paris, London, Rotterdam, Taipei, San Jose, Oakland, and Index, Washington, in the Cascade Mountains. I can hear their voices over my computer speakers and they can hear mine, even though the birds chattering outside my window are not California bluejays but kookaburras, cockatoos, and rainbow lorikeets.

All of our software and hardware tools are off-the-shelf, available to anybody with a modest budget, creating a two-way, smooth, audible stream of voices and images. We are creating something collaboratively that would have been unimaginable five years ago.

One Tradition, Many Languages – Now English

Buddhist scriptures have been around in Asian languages since the third century BCE. Four hundred years later they began to move from Pali and Sanskrit, Indian canonical languages, into Chinese. From Chinese they disseminated into East Asia, with translations emerging in Korean, Japanese, and Vietnamese. And the Buddha’s voice can be read in English since the late Chan Master Hsuan Hua came to the United States from his native Manchuria and spent 30 years teaching English speakers and readers. In daily sessions he explicated the Avatamsaka Sutra line by line.

Rev. Heng Sure speaking about the Avatamsaka Sutra at the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery.

The task before our translation group is to render it into English, a text known as “the king of kings of Buddhist sutras.” In English we have only one other complete translation extant, and it has a deserved reputation for omissions and other infelicities. The Buddhist Text Translation Society, with whom we work, has published only a few of its forty chapters. Now we have tackled it sequentially from the beginning.

When this scripture was rendered into Chinese from Sanskrit it was done by a committee of monks and scholars numbering in the hundreds, sometimes including the emperor himself, or empress, in some cases, when the reign favored Buddhism or wanted its blessings.

Our collaborative format, aided by technology and the internet, follows along behind great translator-monks of the past … Venerable Kumarajiva (344-413 CE), Master Xuanzang (c. 596 or 602-664), and the Monk Fazang (643-712 CE), a favorite of the Empress Wu Zetian (c.625-705), to name a few. In their assemblies scholar-practitioners gathered to translate the texts, including monks from India and the Silk Road kingdoms who could read the original manuscript aloud in Indian languages.

Then there were pilgrims, editors, polishers, certifiers, clouds of scribes, and musical liturgists who invoked spiritual presence and blessings on the work and who dedicated the merits at the end of each day. Sometimes the imperial ministers present lavishly funded the enterprise, building halls and dwellings for the monastic translators and their staffs and occasionally serving as liaison between the palace and the monastery.

In the Golden Era of the Tang Dynasty (6th to 10th centuries CE), hundreds of monks and scholars took part in imperially sponsored translation assemblies, and manuscripts were painstakingly copied by hand. In the digital age today it is a challenge to find half a dozen monks and nuns to sit together; how much the more difficult is it to gather talented translators or experts in Sanskrit, Buddhist Chinese, and English prose. Yet with several key-strokes, today we can send copies of our translations around the world, and the numbers improve.

Some voices lament monks working with technology, as if the only proper monastic vocation is prayer. In fact, monks have always been leaders in technology. The earliest printed book was created in 868 CE, a woodblock print of the Vajra or Diamond Sutra. European monks kept Western civilization alive during barbarian invasions – think Celtic monks illuminating manuscripts in tall towers, tranquil and serene above the Visigoths plundering the market towns and burning the farmhouses below. By preserving and translating textual treasures from the past, monks give readers today and in the future access to the wisdom of the ages. Monks’ tools have moved from quills and colored inks to keyboards and printed circuits, but the intent and the effort is identical with their predecessors throughout history.

Today we enjoy special new tools – the collaborative resources of online wiki-style dictionaries, glossaries, and indices are a reality. Underneath the cursor in one’s browser are resources that heretofore required the presence of an East Asian Library in your neighborhood. These tools live online, in the cloud, and in your browser.

Positive Influence on Buddhist Intrafaith Relations

Another advantage of the digital world for Buddhist translation work is the unprecedented ability to access texts from the different schools of Buddhism. Throughout history the Buddhist community in Asia has experienced partisan schisms: the Theravada, or southern school, avoided the Mahayana, or northern school. The Vajrayana school held itself apart from both the others. Now, though, with the ubiquity of the digital world one can compare texts from all three schools and learn the genuine differences free from bias, stereotypes, and bigotry born of distance.

Some people say that translation by committee creates a “camel-leopard,” something that never existed between heaven and earth, a dysfunctional, hybrid animal. Translating the sutra with a group of men and women monastics while balancing Sanskrit, Tang Dynasty Chinese, and contemporary English prose might seem the perfect cradle for the birth of a camel-leopard.

My experience suggests otherwise. The spirit of collaboration, of give-and-take, of mutual joy in the exploration of this ancient wisdom, is the spirit that prevails in our virtual translation room spanning the planet. Someone asked one of our senior translation hands, “How is it that these young interns come back each week to join our translation group? They’re teen-agers. You’d think that translating ancient texts would be boring beyond belief.” The translator answered, “I would say it’s because they like to watch adults having fun with the Dharma.” It’s always been true in the East, and now in the West as well, bringing ancient wisdom into a 21st century world.