Moving Beyond Tolerance

By Jeffery Long

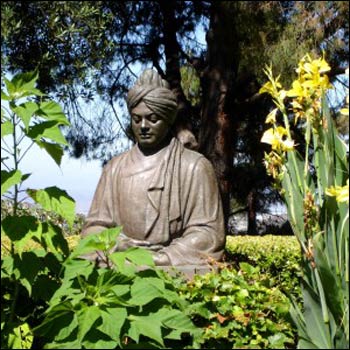

Swami Vivekananda Statue at Ramakrishna Monastery, California

Among Swami Vivekananda’s most significant contributions to global culture are his reflections on religious pluralism, which can be defined broadly as the idea that there is truth to be found in many religious traditions and not only one. Inspired by his master, Sri Ramakrishna Paramahansa, Swami Vivekananda articulated a vision of interreligious harmony and cooperation that is even more desperately needed today than it was over a century ago, when Swamiji proclaimed it at the 1893 Chicago World’s Parliament of Religions.

This paper will present some of the main features of Swami Vivekananda’s thought on religious pluralism –the distinction between acceptance and tolerance, the fact that the world’s religions are not “all the same,” the idea of non-conversion, and the idea of mutual enrichment among diverse traditions.

Beyond Tolerance to Universal Acceptance

In a world marked by violence and pronounced intolerance amongst the adherents of diverse worldviews, one hears a good deal about the virtues of tolerance, and calls for tolerance are an increasingly prominent feature of public discourse. But well intentioned as these calls certainly are, is mere toleration of difference the best that humanity can do?

Swami Vivekananda envisioned interreligious relations that would go far beyond the secular ideal of tolerance, where practitioners of diverse traditions merely co-exist, toward an ideal of universal acceptance. In his famous first address at the World’s Parliament of Religions, he says of the Hindu tradition, “I am proud to belong to a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance. We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true.” Tolerance is, of course, far preferable to intolerance. It is, however, a lesser virtue when compared with acceptance.

In a 1900 lecture entitled “The Way to the Realisation of a Universal Religion,” Swamiji draws a stark distinction between the lesser virtue of tolerance – which he goes so far as to equate with blasphemy – and the much greater virtue of acceptance, saying, “Our watchword, then, will be acceptance, and not exclusion. Not only toleration, for so called toleration is often blasphemy, and I do not believe in it. I believe in acceptance.” His rejection of tolerance is clearly not an endorsement of intolerance but a call to move to the even higher plane of acceptance. As he explains, “Why should I tolerate?

Vivekananda in Alameda, California, 1900 – Photo: oldindiaphotos.in

“Toleration means that I think that you are wrong and I am just allowing you to live. Is it not blasphemy to think that you and I are allowing others to live? I accept all religions that were in the past, and worship with them all; I worship God with every one of them, in whatever form they worship Him.” As I sometimes ask my students, if one of your friends were to say to you today, “I tolerate you,” would that be a compliment? How do we feel if someone tells us that they merely tolerate us? What gives them the right to decide who is allowed to exist and who is not? And what gives us the right to do that to another? We would of course not want toface the alternative of intolerance, which is all too prevalent in the world today.

But tolerance alone is not enough. We can tolerate someone while ignoring them. But to truly see the divine in all, which is what Vedanta teaches us to do, we must go beyond the minimum requirement of tolerance and move toward acceptance. We must see the other not as other, but as our very own. Indeed, this is the teaching not only of Swami Vivekananda but also of Ramakrishna’s wife and spiritual companion, the Holy Mother, Sarada Devi, who tells all of us, “Learn to make the world your own. Nobody is a stranger. The whole world is your own.”

This is true acceptance, based on the deep Vedantic insight of the fundamental unity and inter-connectedness of all beings.

One can perhaps draw a parallel between these three states of being – intolerance, tolerance, and acceptance – and the Yogachara Buddhist teaching of the three levels of truth: falsehood (corresponding to intolerance, which sees the other as a threat that cannot be allowed to exist), relative truth (corresponding to tolerance, which sees the other as a being with its own integrity and value that must be allowed to exist despite its problematic otherness), and absolute truth (corresponding to acceptance, which realizes the ultimate non-duality of self and other).

As one moves through progressively higher states of realization, one goes from a deluded identification with the physical body and its various adjuncts (such as relations of family, ethnicity, nationality, and even species), which can be destroyed and therefore need to be protected from the strange and different, to an intellectual identification with the whole (issuing in the virtue of tolerance, needed for the survival of civilization, but woefully inadequate to a higher spirituality), to the full realization of one’s unity with the whole, issuing in and also sustained and facilitated by the virtue of acceptance.

“We’re One, but We’re Not the Same”

A memorial for Swami Vivekananda at Kanyakumari in southern India. – Photo: Adam Jones, Global Photo Archive, Wikimedia Commons

However, to paraphrase my friend and colleague Anantanand Rambachan, non-duality is not to be confused with simple oneness. Or to quote the famous song by U2, “We’re one, but we’re not the same.” The universal acceptance that Swami Vivekananda teaches should not be taken to mean that all religions are simply the same. Critics of what some call Swami Vivekananda’s “radical universalism” have either misunderstood or distorted his religious pluralism as a teaching that “all religions are the same.” They have then attacked this strawmanposition, which in fact bears little or no resemblance to Swamiji’s actual teaching on this subject.

Some also deride this teaching as a form of relativism – the view that everything is true, and therefore nothing is true. Relativism, a form of skepticism, is rooted in the idea that we can never really know the truth, and therefore all attempts to express truth are of equal value.

Sounding the Deathknell of Fanaticism

Swamiji said at the end of his first address to the World Parliament of Religions, “I fervently hope that the bell that tolled this morning in honour of this convention may be the death-knell of all fanaticism, of all persecutions with the sword or with the pen, and of all uncharitable feelings between persons wending their way to the same goal.” It is a deep and tragic irony that this speech was delivered on September 11, 1893 – that is, precisely 108 years to the day before the notorious attacks which, for many in our time, have come to symbolize that very fanaticism, persecution, and hatred which Swamiji so profoundly hoped would be ended in his time. Clearly, much work remains to be done to realize Swami Vivekananda’s fervent hope.

As long as there is religious bigotry, and as long as violence is carried out in the name of religion, the need for Swami Vivekananda’s vision will be pressing and urgent. This becomes all the more evident when one takes into account the destructive capacities that our ever-increasing technological abilities make available to an ever-widening pool of actors on the global stage. The urgent need to save our world from destruction by promoting the Vedantic vision of universal acceptance compels us, in Swamiji’s words, to, “Arise, awake, and stop not until the goal is reached!”

This article is drawn from a lecture Dr. Jeffery D. Long delivered to the Center for Indic Studies at the University of Massachusetts, New Dartmouth, last July at a conference celebrating Vivekananda’s 150th birthday. The full text of his lecture is available here.