By Paul Brandeis Raushenbush

COLLABORATING TO END POVERTY AND CONFLICT

When Secretary John Kerry took over the State Department from Secretary Clinton, he found that the legal and conceptual framework for an Office of Faith-Based Community Initiatives had already been laid. Deciding to go ahead with the new office, Kerry called a professor of theology at Wesley Theological Seminary named Shaun Casey, who happens to be one of the most religiously knowledgeable and connected people in Washington.

Responding to the opportunity, Prof. Casey took a leave from his position at the seminary and, since the middle of the summer, Casey has been busy launching the new initiative in the hopes that awareness about religion and religious actors will someday be included in the training and day-to-day execution of America’s foreign policy.

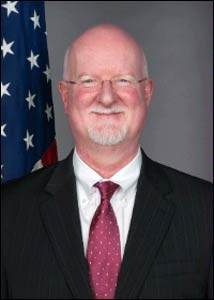

Professor Shaun Casey – Photo: U.S. Department of State

I recently spoke to Prof. Casey, who now has the title of ‘Special Advisor’ on the phone about the exciting work he is doing, what he hopes to be the future of religion at State, and why his wife tells him to wipe that dopey grin off his face when he comes home from work.

Paul Brandeis Raushenbush: Ok, so why are you having so much fun at your new job at State?

Special Advisor Shaun Casey: Well there was never an office like this and there is universal affirmation that the State Department needs a capacity to understand the political and social implications of lived religion across the globe in order to advance our foreign policy. As Secretary Kerry said at the roll-out for the office, ‘We ignore the role of religion at our peril.’

So I get to come to work every day in a building with thousands of people who are fighting extreme poverty, expanding human rights and are trying to mitigate conflict and build peace around the globe.

How are you deciding where to prioritize?

Basically, I have three jobs. The first is to advise the Secretary on specific policy issues in terms of how religion cuts across that issue.

The second mission is to help build the capacity for religious engagement in this building. We have some examples in the past where the United States government has done some good things in terms of engaging religious actors but it has often been ad hoc and personality driven; and never had a systematic strategy. How do we draw a picture that includes the public force of religion politically and in civil society in these countries where we have embassies? How do we change our training here to make it a routine part of our vision of diplomacy that we have people who understand how to interpret religion.

And the third job is to make this office be a conduit or connector for faith-based groups and NGOs.

If you had all the foreign service folks in a room, what one piece of advice would you give them that they might not get from anyone else.

One of our first tasks is to study a handful of countries to see what has worked historically in terms of religious engagement and build some best practices. We want to think about the skill set among U.S. State Department personnel that has led to those successes and teach that skill set in the Foreign Service Institute.

Is there a religious component to the training that the Foreign Service Corps get now?

There is currently an elective course offered in religion and foreign policy and I got invited to teach a one-hour session. It’s a four day course, so I sort of parachuted in briefly and talked about the concept of ‘lived religion’ in which you ask the questions: What difference does it make that one affiliates with a particular religion, in a particular location, and how religion gets lived out in a population?

That takes anthropological skills. It takes the ability to interpret religious symbols, and so you have to have a ‘trained curiosity.’ I think those are skill sets that can be taught. And so I like to call it ‘sophisticating your curiosity’ to look for the religious story and the power of religion within a particular country in which you might be working.

What is the way that the State Department can work with people of faith abroad knowing that the goal of the State Department is not only altruistic but also to serve the interest of United States?

That’s a great question because we do have a foreign policy and we need to be transparent about that. If you are patronizing or you have a hidden agenda, religious leaders pick up on that very, very quickly.

However, religious leaders do care about fighting poverty. And if a country is experiencing extreme poverty, they are looking for partners and the United States government can be a powerful partner. Or when there is a country where there are violations of human rights, religious leaders often are the folks who are trying to defend those oppressed minorities so that there is an overlap there I think between U.S. foreign policy and religious leaders.

Also, while in some places religion feeds conflict, religious leaders and communities can be the most powerful forces for mediating, preventing and ending conflict.

Does your office also have money to give out? What is the role of funding religious groups?

We do not make any grants.

What would success look like for your office fifty years from now?

Several things come to mind. One is that religious groups know we’re here and they can register their policy insights with us.

Secondly, I would hope that we could point to conflict-prone areas and be there with resources before they become expansively violent. I also hope we can come in places that are already violent and help turn the temperature down.

We are in a remarkable time in global history where hundreds of millions of people are being lifted out of extreme poverty. I hope that trend continues. You look at what’s happening in terms of HIV prevalence. You look at the fight against malaria – there are faith-based groups at the van guard of that – often times with U.S. government dollars funding their work. I hope we can look back for 50 years and see that malaria is under control.

I think we could see some bold calls to end extreme poverty for instance by 2030, and I think faith-based groups are going to be part of that. I think the U.S. government will sign off on that. I hope that we can see greater global progress. I would also like to talk about human rights.

I’m not always clear of the motivations that people talk about religious freedom rights..

International religious freedom rights are important, but that’s not all I mean by rights. I think faith groups have a role to play in LGTB rights globally; and rights of disabled people all around the globe. In fact probably the first concrete thing the Secretary asked me to do was education on the disabilities treaty that is about to be the subjects of hearings in the Senate.

I think 130 countries have ratified the treaty, we have not. Secretary Kerry has asked me to educate faith groups because, in fact, most faith-based groups understand the need to protect international disability rights; and they see this treaty as a chance to protect the rights of hundreds of million people going forward.

This interview was originally published by Huffington Post Religion on November 18, 2013.