By Marcus Braybrooke

A PRACTICAL COMMITMENT TO A NON-VIOLENT SEARCH FOR PEACE

Dr. Daniel Gómez-Ibáňez was accused of being wildly optimistic when he said, at the first planning meeting of the 1993 Parliament of World Religions, “We should prepare for 400 people.” At the event, nearly 30,000 people packed Grant Park for the final evening. The Parliament was a wake-up call to the members of all religions to come together to address the critical issues facing humankind.

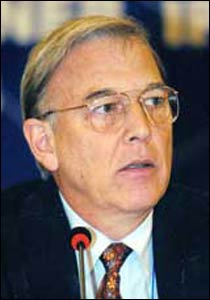

Dr. Daniel Gómez-Ibáňez – Photo: Peace Council

Even before the Parliament had ended, though, the thoughts of its creative executive director, Dr. Gómez-Ibáňez (who has an amazing worldwide range of contacts), were moving on. How was the call to “effective interreligious co-operation” to be achieved in places stained with the blood and haunted by the memories of bitter conflict and not just by clapping in the Ball Room of the Palmer House Hotel? The Peace Council was his attempt to answer the question.

Compared to the huge size of the Parliament, the Council was to be very small – perhaps 25 people “whose spirituality was expressed in practical commitment to a non-violent search for peace and who are respected for what they do and how they live, not because they hold highoffices” (although some do).

The hope has been that by mutual support Peace Councillors can strengthen each other in their particular work and, by an international presence, warn governments that abuse of human rights would not go unseen or unchallenged.

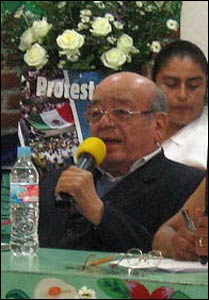

One of the best examples of the way the Peace Council works was its meetings in San Cristóbal de las Casas in Chiapas, Mexico, at the invitation Bishop Samuel Ruiz Garcia, a long-time campaigner against the oppression of Mayan indigenous people.

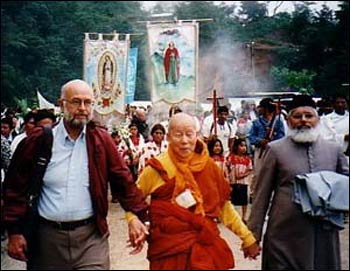

Paul Knitter, Maha Ghosananda, and Irfan Ahmad Khan in San Cristóbal de las Casas – Photo: Marcus BraybrookeOn

New Year’s Day 1994, the rebel Zapatitsa National Liberation Army came out of the jungle, occupied San Cristóbal de las Casas – the capital of Chiapas – and demanded economic justice. Hostilities were quickly brought to an end, and within nine days a ceasefire was agreed, largely thanks to the Bishop’s mediation.

The situation was still tense in 1996 when Councillors met with human rights groups, representatives of the government and – most memorably – with Zapatista leaders at a secret forest location.

Bishop Samuel Ruiz Garcia speaking at a rally for Mayan indigenous rights. – Photo: Wikipedia

On the final night, the cathedral – decorated with banners showing the symbols the world’s religions – was packed for its first interfaith service. At the end, Peace Councillors mingled with the congregation lighting candles until the whole cathedral was filled with light.

Subsequently the Peace Council highlighted further abuse of human rights and gave money to replace the bread ovens and looms which had been destroyed by the paramilitaries. The Mayans could again weave their traditional cloth and not wear Western cast-offs.

Few Councillors, however, expected to be back in Chiapas within a couple of years. Just before Christmas 1997, a group of refugees who had been expelled from their land came for help to the remote village of Acteal. They were pursued by the paramilitaries, and 45 of them – mainly women and children who had taken refuge in the chapel – were gunned down.

BishopSamuel Ruiz invited members of the Peace Council to join him on All Souls’ Day – the Day of the Dead – at Acteal, to dedicate a memorial to the victims. In pouring rain, the Councillors reached the village and slithered down a muddy bank to the chapel. The service with prayers offered by an imam, a rabbi and a Buddhist monk as well as by Christians of many traditions, was intensely moving. One widow, who had lost several children, said afterwards, “My suffering is not over, but the prayers have given me hope.”

The International Committee for the Peace Council – Photo: Peace Council

Meetings in Jerusalem, Bangkok, and Belfast have been equally significant, and Korea deserves special mention. In 1998, a small delegation went there to explore the possibility of facilitating some communication between North and South Korea. The Peace Council, which was almost alone in sending medical supplies that had been specifically requested and were supplied with no strings attached. This gained the trust of the North Korean government, and a small delegationvisited the country; unhappily, this has not led to the hoped-for dialogue between North and South Korea.

The Council, however, has maintained its concern for the Korean situation. In 2007 it was invited to Hwaecheon – a small town situated close to the defensive lines which separate the two Koreas – for the dedication of the Peace Bell Park. Members also went to the Korean Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) and looked across to North Korea. The Peace Bell will be rung when Korea is reunited. The Council’s message included this reflection on the significance of bells:

Bells play an important part in many religious traditions.

They are tolled in times of sadness;

They are rung as a warning;

They are used to call the faithful to prayer;

Their peals mark times of joyful celebration.

The Peace Bell reminds us of the tragic destruction and loss of life caused by war as well as the damage to the environment.

The Peace Bell warns us of all the dangerous divisions in our world, of the misuse of religion to support violence and the horrors of war.

The Peace Bell calls people of all countries and religions to pray for a healing of past divisions and the creation of a just world order.

The Peace Bell, which will be rung on the reunification of South Korea and North Korea, will, we hope, celebrate the coming of peace everywhere for everyone.

Other meetings, in more peaceful locations, have addressed vital issues such as environmental degradation, economic injustice, women’s rights, the dangers of population growth, and the spread of HIV. The most recent meeting in 2013 was near Rome as part of the Awakened World gathering, arranged jointly by the Association of Global New Thought, the Interreligious Engagement Project and the International Peace Council. The Peace Council co-ordinator is now Jim Kenney, who has a life-time’s experience of interfaith engagement. The Council needs greater financial resources to make full use of its rich human resources.

The Peace Council also took an active role in the campaign to ban land mines and arranged interfaith prayer services at some conferences. A Canadian diplomat told me that these were the only times which brought together representatives of governments, NGOs and victims, who for most of the time sat on opposite sides of the table. Archbishop Desmond Tutu wrote this moving prayer for these services.

Lord, how can I serve you without arms?

How can I walk in your way without feet?

I was collecting sticks for the fire when I lost my arms,

I was taking the goats to water when I lost my feet.

I have a head but my head does not understand why there are land mines in the grazing land or why there is a trip wire across the dusty road to the market.

My heart is filled with a long ache. I want to share your pain but I cannot. It is too deep for me. You look at me but I cannot bear your gaze. The arms factory provides a job for my son and my taxes paid for the development of “smart” bombs. I did not protest when the soldiers planted fear into the earth that smothers the old people and the anxious mothers, and fills the young men with hate.

Lord, we are all accomplices in the crime of war, which is a lust for power at all costs. The cost it too much for humanity to bear.

Lord give us back our humanity, our “ubuntu” …

Teach us to serve you without arms.

Amen