By Marcus Braybrooke

THE EARLY YEARS OF THE INTERFAITH MOVEMENT

The legacy of the 1893 World Parliament of Religions did not live up to the high hopes of its organizers. The dream of a new era of universal peace too soon became the bloody nightmare of twentieth century battlefields and genocide.

Pope Leo XIII – Photo: en.wikipedia

Pope Leo XIII officially censured the Roman Catholic speakers at the Parliament and forbade participation in “future promiscuous conventions.” The openness to other faiths shown by many Christians at the 1910 World Missionary Conference in Edinburgh was soon obscured by Karl Barth and Hendrik Kraemer, who stressed the distinctiveness of the Gospel over against other religions, which, they proposed, were a futile human effort to reach God.

Yet there was a legacy. The Parliament created awareness among some that there are “wells of truth outside Christianity.” Historian Sidney Ahlstrom said it began the slow change by which Protestant America was to become a multi-racial society. Swami Vivekananda and Dharmapala established continuing Vedanta and Buddhist groups in the United States.

The Parliament also stimulated the academic study of religions. The Haskell lectureship endowment at the University of Chicago brought distinguished scholars of “comparative religion” to the school and enabled Henry Barrows, secretary of the Parliament, to lecture in Asia.

In 1901 the first meeting of the International Congress for the History of Religions (IAHR) was held as part of the Paris Universal Exposition, though this was for the scientific study of religions and not for interfaith dialogue. The distinguished scholar Joseph Kitagawa wrote, “it becomes clear that what the Parliament contributed to Eastern religions was not comparative religion as such. Rather Barrows and his colleagues should receive credit for initiating what we call today the ‘dialogue among various religions,’ in which each religious claim for ultimacy is acknowledged.”

Initial Institutional Developments

IARF activities continue today around the world. This recent gathering was in Andhra Pradesh in India. Photo: iarf.net

Plans for another Parliament in 1901, possibly in India, came to nothing – although small scale parliaments were held in Japan and elsewhere. The obvious ‘child’ of the Parliament was the International Association for Religious Freedom (IARF), as it is now known, which held its first meeting in 1900. The prime mover was Charles William Wendte, born in Boston in 1844, who had helped plan the 1893 Parliament. His parents had come to the United States on their honeymoon and stayed on. Wendte’s father becamea Unitarian after being astonished to hear “something sensible from a preacher!” To his delight, his son became a Unitarian minister.

Besides his congregational responsibilities, Charles Wendte built up close relations with the German Free Protestant Union. With the American Unitarians, they were the main supporters of IARF, though among the 2,000 participants at the 1907 Boston Congress were some members of the Brahmo Samaj and a handful of liberal Jews, Muslims, and Catholics. (A longer profile of the IARF will be published here later this year.)

The World Congress of Faith can claim a more distant relationship. Its links with the 1893 Parliament came through the “Second Parliament of Religions,” held in Chicago in 1933, in conscious imitation of the earlier event. The 1933 Parliament, a largely forgotten event, was initiated by Charles Weller and Mr. Das Gupta. Weller, a social worker, started the League of Neighbours in 1918 to help integrate African Americans and foreign-born citizens into American life.

Das Gupta had come in 1908 from India to England. To help remedy British ignorance of India, he organized the Union of East and West. Then in 1920 he accompanied Rabindranath Tagore to the United States. Das Gupta stayed on and restarted his Union of East and West in America. Early in the 1920s he met Weller. Together they merged the League of Neighbours and the Union of East and West to create the Fellowship of Faiths. The Fellowship arranged in several cities meetings at which a member of one faith paid tribute to another faith. It also published a journal called Appreciation.

In May 1929, the World Fellowship of Faiths met in Chicago. This revived memories of the city’s 1893 Parliament and led to a similar event being held to coincide with the Second World Fair in 1933. Twenty-seven gatherings were held in Chicago, with a total attendance of 44,000 people. Preliminary meetings were also held in New York. Bishop McConnell claimed, perhaps unfairly, that the 1933 gathering was an advance on the 1893 event. “The first difference,” he said, “is that instead of a comparative parade of rival religions, all faiths were challenged to apply their religion to help solve the urgent problems which impede man’s progress. The second difference is that the word ‘faiths’ is understood to include not only all religions but all types of spiritual consciousness.”

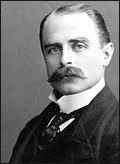

Sir Francis Younghusband – Photo: Wikipedia

One of those who attended the 1933 Parliament was Sir Francis Younghusband, who three years later arranged the first World Congress of Faiths in London. The minutes of the first planning meeting make clear the link with the World Fellowship of Faiths, which had arranged the Second World Parliament of Religions in 1933. Younghusband soon made clear to Das Gupta that, although grateful to him and the World Fellowship of Faiths, that he – Younghusband – was in charge of the Congress.

The World Fellowship of Faiths described itself as “a movement not a machine; a sense of expanding activities, rather than an established institution, an inspiration more than an achievement. It has never sought to develop a new religion or unite divergent faiths on the basis of a least common denominator of their convictions. Instead, it held that the desired and necessary human realization of the all-embracing spiritual Oneness of the Good Life Universal must be accompanied by the appreciation (brotherly love) for all the individualities, all the differentiations of function, by which true unity is enriched.” This is still a fair description of the interfaith movement.