By Paul Chaffee

WHEN WHO WE ARE BECOMES MORE IMPORTANT THAN WHAT WE BELIEVE

A week after 9/11, on a Monday afternoon, 400 clergy in vestments assembled in Civic Center, San Francisco, a rainbow of color representing an unprecedented diversity. They processed into Bill Graham Civic Auditorium where 5,000 had gathered to mourn the terrible tragedy the nation had suffered. After a long, thoroughly interspiritual service, people streamed out. In a far corner of the green a group of people stood alone, protestors, waving posters.

On the way to her car, Rita Semel, a founder of the San Francisco Interfaith Council who helped organize the memorial, was approached by one of the protesters, clearly distraught. “Why didn’t you invite us!?”

Rita asked, “Who are you?” He replied, “We’re the atheists! We’re the humanists. No one invited us.” “We didn’t know how to find you,” she answered.

The Greek word ‘αθεοι’ (atheoi), as it appears on this ancient papyrus in the New Testament’s “Epistle to the Ephesians” (2:12). It is usually translated into English as "[those who are] without God.” Photo: Wikimedia

Twelve years later, atheists have had their own ‘coming out’ celebrations. Today engaging atheists, agnostics, and humanists is much easier. You immediately discover that ‘atheism’ is not a monolithic movement but rather a potpourri of communities, often in disagreement (much like the conflict found within religious traditions).

Some factions are angry and categorically anti-religious. But others wish to relate to people of faith, particularly in service and in ‘tikkun olam,’ or healing the world. They wish to mourn when the community mourns, celebrate when the community celebrates, and be included in the interfaith community as it does its work. We agree that ‘interfaith’ is an inadequate descriptor of what we are about, but it is the best we have for now.

Important voices like Alain de Botton, in his recent book Religion for Atheists, Nicholas Kristof in his New York Times essay “Learning to Respect Religion,” and Hemant Mehta, the Friendly Atheist, have been offering wise counsel about building healthy relationships between religionists and non-religionists. The time is overdue for people of faith to reciprocate.

A Matter of Justice and Values

Anyone holding high the need to respect every human being, then demonizing those whose worldview doesn’t include a deity, is disingenuous or not thinking clearly. Globally, among the 1.1 billion unaffiliated with any religious tradition, hundreds of millions fall into a non-theistic, non-religious category. Demonizing this vast group of our kinfolk is antithetical to the inclusivity we profess and badly betrays values such as compassion and love, values which form the spiritual root structure of most religions.

The demonization to date has taken a heavy toll. As Chris Stedman indicates in this issue, U.S. pollsters report that atheists are the most feared people in the land, bringing untold grief to them, prejudice, and, from certain rabid right-wing Christians, blame for every ill on earth. All this for having a different understanding of life and the universe than “religious” people.

The bigger picture is even worse. Last December Robert Evans wrote “Atheists around World Suffer Persecution, Discrimination,” an article beginning with this sobering fact:

Atheists and other religious skeptics suffer persecution or discrimination in many parts of the world and in at least seven nations can be executed if their beliefs become known, according to a report issued on Monday.

Evans’ point comes from a study the International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) released on U.N. Human Rights Day last month, titled Freedom of Thought 2012. It points out that, officially, expressing atheist views is cause for capital punishment in Afghanistan, Iran, Maldives, Mauritania, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan.

IHEU’s logo

Equally disturbing are discriminatory laws in the United States and some European countries. The 70-page report notes “laws that deny atheists’ right to exist, curtail their freedom of belief and expression, revoke their right to citizenship, restrict their right to marry.” Other laws “obstruct their access to public education, prohibit them from holding public office, prevent them from working for the state, criminalize their criticism of religion, and execute them forleaving the religion of their parents.”

Clearly, atheists are being discriminated against unjustly and deserve not only a welcome, when they want to join interfaith communities, but an apology and a buttressed defense against continued bigotry.

The good news is that all sorts of religious/non-religious interaction have been bubbling up since the turn of the century. Atheists-at-the-interfaith-table is still a tart new idea to many, but the relationship building is well on its way.

The Benefits of Inclusiveness

Nearly half a century ago, in Rossmoor, California, a senior community of about 10,000 residents created an interfaith council, one of the earliest in the country. A favorite program has been a series of Atheists & Believers conversations; people simply getting together each month to talk about what they believe, or don’t. “What we discovered” through years of meetings, reports one still-amazed leader, “is how very alike we all turn out to be!”

Similar results were reported after including non-theists at the large Interfaith Youth Core’s Leadership Institutes held across the country each year. That success led IFYC to sponsor an Atheists and Evangelicals: Common Ground blog. Finding young people using high technology to build new bridges is inspiring. More startling still, last month 300 clergy and lay leaders attended the 13th annual interfaith Russia’s National Prayer Breakfast in Moscow, an event focused on shared concern for “the common good,” reports William Yoder. This year they heard, among others, “the non-believer Andrey Tumanov. This assumes that atheists too can play a role in Russia’s moral revival.”

Campus chaplaincies have been ahead of the curve regarding interfaith engagement and welcoming the non-religious. Humanist-atheist ministries have been established at American University, Columbia, Harvard, Rutgers, and Stanford. At the University of Toronto, two of the 32 chaplains introduced on their website are listed “Humanist,” on a team including Evangelical Christians and Pagans, one might add.

Equally fascinating are the occasional atheist churches beginning to emerge. Esther Addley in the Guardian reports that Sunday Assembly in London is “a godless congregation that meets … to hear great talks, sing songs and generally celebrate life.” Says one congregant, “I came last time and really enjoyed it. It’s got all the good things about church without the terrible dogma. I like the sense of community – and who doesn’t enjoy a singsong?”

Pastor Klaas Hendrikse, affiliated with the mainstream Protestant Church in the Netherlands (PKN), does not believe in a supernatural God or an afterlife, Robert Pigott reports. “No, for me our life, our task, is before death,” says Hendrikse. Conservatives tried to defrock him when he published Believing in a Non-Existent God, but too many in his parish agreed with him, as does one in six PKN clergy. In this issue of TIO, Gretta Vosper tells of her own journey as the atheist pastor of a thriving, evolving Toronto congregation.

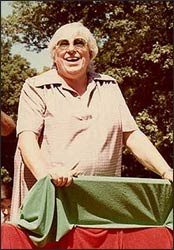

Madalyn Murray O’Hair in 1983 Photo: Wikimedia

Last month the American Atheists held a convention celebrating 50 years since their 1963 founding, under the leadership of Madalyn Murray O’Hair. Her cause, so startling at the time, and held so passionately, led Time to call O’Hair “the most hated woman in the country.” That pioneering courage, her willingness to stand up for what she believed in the face of almost universal condemnation, provided the first steps in setting up the possibility for a conversation and healthy relationship between American theists and atheists.

The time has come now to put out the welcome mat, open the door, and make new friends, including those in our midst already who were fearful for sharing who they really are till now. The welcoming is not just for their sake, or ours, but for the sake of whole human family.

![The Greek word ‘αθεοι’ (atheoi), as it appears on this ancient papyrus in the New Testament’s “Epistle to the Ephesians” (2:12). It is usually translated into English as "[those who are] without God.” Photo: Wikimedia](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/577bc3e5cd0f68c0f253247c/1485985330049-B7A74QUQ4TZ2VH9140F4/image-asset.jpeg)