By Christopher Key Chapple

HOW RELIGIOUS DIVERSITY BECAME A REALITY IN AMERICA

The religious landscape of the United States permanently changed with the advent of new immigration legislation inspired by the Civil Rights movement in 1965. Before this time, it was extremely difficult if not impossible for individuals from non-Christian nations to reside in the United States permanently or to become citizens. Over the course of nearly 50 years, millions of new immigrants have brought faiths from all corners of the world to the United States, prompting a time of encounter, dialogue, and in some cases, misunderstanding.

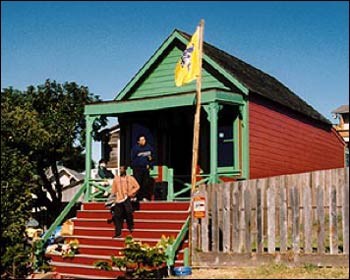

In the 19th century, although Chinese men were recruited to work on the railways, Chinese women with rare exceptions were not allowed into the United States. Because of anti-miscegenation laws, Chinese men were not allowed to marry. Many of the Chinese laborers returned to Asia or died childless. Their temples, known as “Joss Houses” designed for the veneration of Confucius, Lao Tzu, and Buddha, fell into disuse. One such example can be seen in Mendocino, California, though many have been demolished. At one time a sizable percentage of the population of Montana was Chinese, as well as of California and Washington.

Mendocino Joss House – Photo: David Look, NPS

However, due to fear of the “Asian Threat” and the “Yellow Peril,” stringent laws were passed known as the Asian Exclusion Act in 1880. Only the Japanese were protected, due to their relative political and economic strength during the time of Meiji rule (1868-1912). Families of Japanese workers were allowed to migrate to Hawaii and California.

In 1920, a number of men from the Punjab, in India, entered the United States as farmworkers. The Punjabis, largely Sikhs, skirted the anti-miscegenation laws by marrying Mexican women of identical skin tone. In 1920 new anti-Asian legislation was passed that banned Punjabi farm workers. This legislation effectively prevented all non-Europeans from settling in the United States.

Because the United States had annexed the Philippines after the Spanish American War of 1898, some Filipino men were admitted on work visas until independence was granted in 1946. Workers who had been allowed into the country were given one-way passage back to the Philippines.

Anti-Asian sentiment reached fever pitch in December, 1941 when the Japanese government bombed Pearl Harbor. The good times for the Japanese community in America came to an abrupt halt when more than 110,000 Japanese and Americans of Japanese descent were placed in concentration camps from 1942 to 1945. Because they could not pay their taxes, they lost their land and businesses and, whether Buddhist or Christian, their temples and churches closed until after the war ended.

San Francisco public school students pledge allegiance to the American flag just prior to the internment of Japanese Americans in April 1942 – Photo: Wikipedia

Buddhist Missions of North America, established in the 1880s, changed its name to Buddhist Churches of America (BCA) in 1944 in the concentration camps. The following year, as the returning Japanese began to rebuild their lives, BCA adopted the architectural design of Protestant Churches and replaced Christian symbols with Buddha images. They also modeled their worship services after Protestant liturgies. Sikh sanctuaries called gurdwaras, from earlier in the century similarly made concessions to American style, using chairs instead of sitting on the floor and using the facilities as community centers and as worship space.

The entry of Hinduism into the United States followed a different course. The first swami who gained acclaim in the United States, Swami Vivekananda, spoke at the World’s Parliament of Religions in 1893. During subsequent lecture tours he gathered many American followers, establishing Vedanta Societies in major American cities.

Paramahamsa Yogananda, who arrived before the restrictive legislation of 1920, established a number of meditation centers, primarily in Southern California, that attracted former Christians and Jews. The meeting places for these Hindu movements in America included pews and pulpits, Sunday services with sermons, and other aspects that were more American than Asian. Unlike the Buddhist churches and the gurdwaras, whose members were nearly exclusively Asian, the Hindu groups, with their connections to the Transcendentalists and their successors, such as William James, attracted a largely white following.

When Rev. James Lawson (recently featured in the film “The Butler”) lived as a Methodist missionary in India from 1952 to 1955, where he studied Gandhian techniques of nonviolent resistance. Little did he imagine the profound social change that would occur through his training there in nonviolent civil disobedience.

Not only did integration become the law of the land in the 1950sand 1960s, anti-miscegenation laws were struck down and immigration to the United States, once limited exclusively to Europeans, became available to citizens of all nations in 1965. Each nation was given a starter quota, and each newly admitted resident was then able to sponsor family members. The population of the Indian community now numbers in the millions. With this surge of immigration, American religious identity has shifted from Protestant, Catholic, and Evangelical Christian (with a few million Jews) to include ethnic Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus, among others, as well as many blends of interfaith families and white converts, due to choice and intermarriage.

Shifts in World Religion

To be religiously literate now requires an understanding of the depth and breadth of world civilizations. The prophetic monotheisms arose from the Middle East and spread from Jerusalem and Mecca to the western and northern reaches of Europe, to America, and across Asia to Indonesia. The Buddhist tradition arose in India and spread to the Middle East, Central, Southeast, and East Asia, and with Japanese migration, became the predominant faith of Hawaii. The Hindu faith became prominent for a time in Southeast Asia and remains vibrant on the islands of Bali and Fiji as well as in Trinidad and Tobago, South Africa, and the nations of eastern Africa. Immigrants from all reaches of the globe have brought their faiths to the United States. For instance, in 1980, there were no dedicated centers for Jainism, a faith from India that emphasizes nonviolence. Today, there are 62 vibrant Jain temples and community centers in the United States.

A good clearinghouse for information on American religious diversity is the Pluralism Project at Harvard University, which maintains databases on various faiths, including the Baha’i, Buddhism, Confucianism, Daoism, Hinduism, Islam, Jainism, Judaism, Native American religions, Paganism, Shinto, and Sikhism. Every American city now includes houses of worship for most of the above faiths and interfaith activities are now common among clergy and lay people. Many Americans have developed an eclectic approach to religion and spirituality. It is now not uncommon for Jews to practice Buddhist meditation, for Methodists to practice Yoga, for Catholics and others to become vegetarian, and so forth.

Greater understanding is needed of the entry of new religions into America. Sikhs, for instance, have been mistaken for Muslims with tragic results. In 2012, six Sikhs were shot dead at a Wisconsin gurdwara. On September 15, 2012, a Sikh gentleman in a turban was gunned down and killed a gas station in Arizona, mistakenly assumed to be a Muslim. Although such instances are rare, the tides of prejudice can run deep and more knowledge about religious traditions is essential in order to maintain the important American commitment to religious freedom.

The Shri Swaminarayan Mandir Hindu Temple in Atlanta – Photo: Wikimedia

A truly civil society supports a diversity of races and creeds, allowing for minority faiths to thrive in the midst of majority communities. Great advances have been made to allow for Muslim, Hindu, Jain, Buddhist, Sikh and other religious communities to design and construct buildings in their respective traditional styles, including minarets, elaborately carved sandstone or marble facades, and other hallmarks important to non-Western faiths. With the rise of interfaith marriages and the need for communities to work with one another on topics of joint civic concern, religion will play an enduring role in guaranteeing a just and open society in 21st century America.