By Yona Zeldis McDonough

SOMETHING LOST, SOMETHING GAINED

My latest novel, Two of a Kind, is about a Christian interior decorator and Jewish obstetrician who meet at a posh wedding. They seem to have nothing in common except that they are both widowed and each has a teenaged child. She takes an instant, bristling dislike to him but agrees to take on the assignment of redecorating his apartment because she needs the money. Yet to their surprise, these two seemingly mismatched souls discover they are deeply attracted to one another. But while falling in love is easy, staying in love is not.

They must reconcile their pasts, their cultural differences and blend their lives into a new family – challenges that at times feel impossible. The novel deals with whether they can overcome these obstacles. Fortunately, I can say that this couple comes up with a solution that works for them.

My two main characters are part of a rapidly growing trend: A recent article in the New York Times, using new Pew Research statistics, reports that the intermarriage rate “has reached a high of 58 percent for all Jews, and 71 percent for non-Orthodox Jews – a huge change from before 1970 when only 17 percent of Jews married outside the faith.” It goes on to say that two-thirds of Jews do not belong to a synagogue, one-fourth do not believe in God, and one-third had a Christmas tree in their homes last year. Jack Wertheimer, a professor of American Jewish history at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, was quoted as saying, “It’s a very grim portrait of the health of the American Jewish population in terms of their Jewish identification.”

Now I’m no sociologist, but these are very telling figures, and as a Jew, I understand Wertheimer’s alarm. Jews are in the minority and always have been; if we intermarry, the religious beliefs, traditions, and culture that have come to define us will erode and eventually disappear. But I am someone who has happily been part of an interfaith marriage (we tied the knot in 1985 and are still going strong), so I am going to argue the opposite point of view and say that maybe this dark cloud will turn out to have the proverbial silver lining.

When my husband Paul and I met in 1981, it was not a struggle to determine whether we belonged together. Rather than battling over our differences, we romanticized them. He thought my Brooklyn-Jewish girl background was exotic; I imagined that his Portsmouth, New Hampshire upbringing had been plucked from a series of Norman Rockwell illustrations. Still, our being together was a leap that even ten years earlier we might not have made.

Growing up in the 1960s, I knew of almost no one whose parents were intermarried. In my neighborhood, there were Jewish kids with Jewish parents, and Catholic kids with Catholic parents. A good portion of the latter went to the nearby parochial school, while the Jewish kids went to the local public school. There was no animosity between us, but there was a clear sense of distinction: we knew who we were and where we belonged.

The only exception was the one girl whose parents were divorced (another anomaly in that decade) and whose Jewish mother had remarried an Italian Catholic. This union carried with it a faint whiff of something exciting and even dangerous; he was rumored to own a handgun, though I never actually saw the thing, and an impressive collection of Playboy magazines, which were passed around when her parents were out.

Mine was an essentially progressive and politically liberal family. I was born in Israel, to American parents who had gone to Israel together in the late 1940s. Zionism, not traditional observance, was my father’s attachment to his culture, and he sought to instill it in us as well; we also celebrated some holidays like Hanukkah and Pesach. Yet despite this climate of tolerance, I would occasionally hear such phrases as goy, or goyish kopf as well as the well-known shiksa, and its adjectival form: shiksavatich. It was years before I understood that those terms were slurs; my insulated experience prevented me from comprehending the put down.

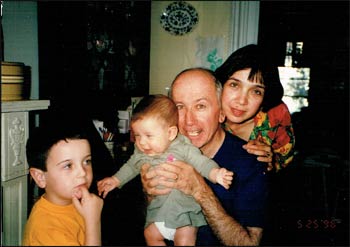

Yona, her husband Paul, and Katherine and James, their children.

Paul grew up going to church regularly, and one of his sisters became a nun. He did not know many Jews because in Portsmouth, there simply weren’t very many to know. His mother had died before we met, but I became close to his step-mother, who threw me a baby shower and once spent an afternoon in the kitchen of our rental cottage in New Hampshire making me twelve fruit pies to “freeze for the winter.”

Yet this same woman, in casual conversation, described how someone attempting to get a lower price on something she was selling had tried to “Jew her down.” I was so upset I could not even speak; it was only later that I was able to tell her how I felt and ask her never to say that in front of me again. Her response? “Honey, I’ve been saying it all my life and I’m not about to stop now. You’re just too sensitive.”

But for my own children James and Katherine, born, respectively, in 1991 and 1995, the whole issue is, well, a non-issue. They understand they have roots in two faiths, neither of which has dominance in their lives. My son had a bris but not a bar mitzvah; my daughter speaks of her desire to go to Israel as part of birthright trip. Many, if not most, of their friends are products of interfaith marriages too, and they don’t see it as anything unusual or even worth remarking on. They will never view either of our religions as strange; they will swim freely in a wider sea.

They will also never hear us utter those seemingly innocuous words and phrases that my husband and I both heard growing up: words denoting both otherness and inferiority, words that are laced with fear, mistrust, and derision. I can’t help thinking that this will be a good thing. It seems to me that historically, there has almost never been a widespread I’m-okay-you’re okay policy when it comes to religion. No, it’s been more like “I’m ok and you stink,” which in turn gives me the right – the mandate even – to discriminate against, convert, expel, persecute, torture and kill you – all in God’s name. Maybe these fierce alliances to religion promote and encourage these feelings and this behavior; it sure looks that way from where I sit. Instead, what if more of us begin to experience the “other” differently, in an up-close and personal kind of way? The children of such unions will no longer feel such a keen sense of “us” and “them” but a more powerful sense of “we.”

The path to this possibly greater good is not necessarily an easy one. In her 2013 book, ’Til Faith Do Us Part: How Interfaith Marriage is Transforming America, Naomi Schaefer Riley points out that what may be good for the group may be more complicated for the individual. She maintains that in the United States, interfaith couples are less happy and are more likely to divorce. Using interviews with married and once-married couples, clergy, counselors, and sociologists, Riley shows that many people enter into interfaith marriages without serious consideration of the issues that divide them and that a cloudy romantic haze obscures potential future problems. Even when such couples do acknowledge deeply held differences, they still believe that love conquers all. If Riley is correct, interfaith couples need to look ahead to the future even more than most, especially if that future includes a desire for children.

Of course there are those, Jews and Christians alike, who are deeply attached to their faith and who would experience a profound loss were they to marry outside it. For such people, an interfaith marriage would be a mistake. But for those whom religious identity is not central (like Paul and me), the melding of the two adds more than it takes away. We celebrate Pesach and Hanukkah with my mother, who wants to provide her grandchildren with the experience of a seder, and a secular but very merry Christmas at our house, complete with bedecked tree, scads of presents and a buffet meal for an-ever growing cohort of friends. An interfaith union provides an extraordinary opportunity to make the political personal, to challenge the status quo, and to embrace the kind of tolerance that will benefit us all. Yes, some things – though not all – will be lost to the Jewish community, faith, and culture. Something precious, however, will also be gained.

This article was originally published November 29, 2013 in Huffington Post.