Women Anticipating the Interfaith Movement

By Allison Stokes

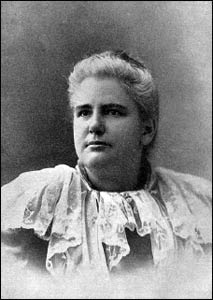

Rev. Anna Howard Shaw – Photo: Wikipedia

When the Rev. Anna Howard Shaw, M.D., preached in May 1893 at an event held during the Chicago World’s Fair, she broke new ground. She did not participate in the first World’s Parliament of Religions held four months later, but her powerful sermon anticipated the Parliament’s inclusive, multi-faith outreach. In retrospect, it might be said that Shaw set the stage for the Parliament. At a time when it was considered improper if not scandalous for women to speak in public, she and the many women who addressed overflow audiences in May at the World’s Congress of Representative Women courageously challenged cultural norms. It is a story that’s been forgotten or ignored, and suggests that Shaw be celebrated as a feminist pioneer in the interfaith movement.

About the Preacher

Anna Howard Shaw was an impressive woman – the first ordained female in the Methodist Church in the United States. Born in 1847, she graduated in 1873 from Albion College, then attended the Boston University School of Theology, where she was graduated in 1876, the only woman in her class. To pay her expenses through college and university, she preached and lecturedin the cause of women’s suffrage. After serving two Methodist churches in Massachusetts, Shaw made history in 1880 when she was ordained by the Methodist Protestant Church. She earned an M.D. in 1886 from Boston University. Shaw met Susan B. Anthony in 1888 and, from that year until Anthony’s death in 1906, the two were rarely separated. At the request of “Aunt Susan,” Shaw delivered the closing address at her funeral and pronounced the final words at her Rochester grave. Rev. Shaw died at age 72 in July 1919, not living to see women win the right to vote the following summer.

The Context

More than 100 congresses were held during the Chicago World’s Fair, or more properly, the World’s Columbian Exposition, which ran for six months from May 1st until October 31st, 1893. The best attended was the World’s Congress of Representative Women, in May; the second best was the World’s Parliament of Religions, in September. Both gatherings convened at the building that is now the Art Institute of Chicago.

In 1894, May Wright Sewall published a two-volume set of the papers presented at the women’s congress. Thanks to her we have the text of Shaw’s sermon, and also an account of the morning worship service, planned and led by clergywomen. Mrs. Sewall herself introduced the event, noting that seated upon the platform were 18 ordained clergywomen, representing 13 different denominations of the Christian church.

Although Shaw had been ordained some 13 years earlier, and had been serving churches before that, for this occasion she wore a ministerial robe for the first time. Along with her robed sisters, they made an impressive group.

Rev. Shaw was not in the practice of writing her Sunday sermons, but for this important occasion she had put words to paper, then memorized them. When Susan B. Anthony asked about the sermon the night before, Shaw decided to deliver it to her as a rehearsal. The preacher was well aware that “Aunt Susan” was extremely anxious that she should do her best, and because it was quite late, she was confident that they would not be interrupted.

The Women’s Building at the World’s Columbian Exposition was the site of the World’s Congress of Representative Women, held in May, 1893. Four months later the World's Parliament of Religions used the building. Today it is the home of the Chicago Art Institute. – Photo: Wikipedia

More than twenty years later, in her autobiography, The Story of a Pioneer, Shaw vividly remembered her friend’s distressing response to this night-time rehearsal. Anthony was disappointed. The sermon was dead. It had no life in it. She blithely called for a new sermon on a different text, then went to her room “to sleep the sleep of the just and the untroubled,” leaving Shaw to toss in her bed “the rest of the night, planning the points of the new sermon.”

Anna Howard Shaw came through. Her eloquent words have enduring power and relevance, speaking not only to the experience of late 19th century women but resonating with 21st century women as well.

The Sermon

As Rev. Shaw spoke to the assembled congregation of some 3,000, her amazing rhetorical skill offered her listeners inspiration, encouragement, support, comfort, and challenge. The opening of the sermon, which was about 30 minutes long, is unremarkable in that it reflects standard practice. Shaw quotes from the Gospel of Matthew, using a passage from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount, “You are the light of the world…”

The direction she takes next, however, is remarkable. Shaw demonstrates a pioneering, multi-faith consciousness by quoting from “the religion of the far east, from Zoroaster,” from “Buddhist scripture,” from “the Mohammedan scriptures,” and from “the Chinese, from Confucius.” She is sensitive to the diversity represented in the Congress. People were there from India, China, Japan, Turkey, Syria, Africa, Iceland, Australia, Mexico, Canada, Central and South America, and most European countries. Affirming of religious difference, Shaw aims to be inclusive, and in so doing in this extraordinary venue, she breaks new ground.

She goes on to recount the liberating experience shared during the week preceding the congress – the papers, the subjects, the discussions. Throughout, there has been “but one cry, the cry to be free; free to be; free to do; free to become that which is best and truest for God’s people everywhere.”

Shaw makes a clear, if oblique, statement that what they have shared together can never be taken away from them. Each one who has endeavored “to lift herself or her sisters on a higher plane of life” has voiced heartache and sadness. Each has felt “the cramping, crippling, and dwarfing power of prejudice and custom.”

Referring to the gathering of women as “our love-feast,” she says that it has taught the world that women are learning the lesson of toleration – “the one lesson which is the hardest for the human race to know.” The “blessed experience” has been one of empowering solidarity with “such oneness of sympathy and oneness of hope, that no woman can ever say truthfully again, ‘I am all alone of all the women in the world.’”

In closing her sermon Shaw quotes a Brahman who said of differences in religious views: “I scan them all, and in and through them all, I gather one truth — divine love.” Shaw then concludes by paraphrasing Jesus, “One is your father, even God; and all ye are brethren.’”

Anna Howard Shaw’s 1893 message touched on many topics, including the subservience of women, the struggle for freedom, the superiority of personal experience over creeds and tradition, the nature of God and revelation, the divine feminine, the character requirements of women in leadership, the nature of Truth, the oneness of humanity, and more. A casual reader of the sermon might suspect that Shaw fell into the trap of the eager, novice preacher: overloading the message. What kept her from this pitfall and made her sermon so powerful was her skill in weaving a clear theme throughout. Her focus was truth, and more specifically, “the truth that shall make us all free.”

Finding Freedom

She asks where freedom may be found. Not through the scholar who answers that knowledge is the highway to freedom. Not through the statesman who answers that constitutions and laws are the highway to freedom. Not through churchmen who answer that creeds are the path to freedom (“Believe and you shall be free.”). No, truth alone can make men and women free. Shaw quotes, but does not name, the late Quaker Lucretia Mott: “Truth for authority, and not authority for truth.”

Shaw boldly puts forth her inclusive, pluralistic understanding of truth. “We have had enough of the creeds. What matters our label so truth be our aim?” Shaw is critical of people who are bound by their own limited vision of truth, people who cry, “My creed, my philosophy, my work is true, therefore all else is false.” Noticeably missing in her sermon are references to Christ. In fact, she hardly quotes Christian scripture at all, even though her Biblical allusions make it plain that she is well grounded in scripture.

Also noticeably missing are personal references or stories. The fact is, the preacher embodied and modeled the strong character that she said enables women leaders to “stand by the truth through moral power” and thus “face social ostracism, prejudice, and denunciation.” In her many references to “obstacles and difficulties,” her listeners could be sure she had endured such herself, but she never explicitly said so. She concludes with a timeless exhortation:

“... And so, my sisters, do not falter; and when they cry, the world is not ready, the world has not been educated up to your truth, call back to the world, “We can not lower our standard to the level of the world. Bring your old world up to the level of our standard.”

In many notable ways Shaw’s message anticipated the work of feminists of the 1960s and 70s. She spoke of the “mother-heart of God,” and declared, “What God needs in humanity today is recognition of the fact that one-half of the divine nature in the world is clothed in womanhood, and unless womanhood is developed, one-half of divinity itself is kept from the knowledge of the peoples of the world.”

Shaw’s sermon of 121 years ago might well provoke an “Amen” from many today.

For the text of Shaw’s sermon and a fuller description of it, see Allison Stokes, “Global Feminism and Inclusion in Anna Howard Shaw’s 1893 Sermon” in Postscripts, The Journal of Sacred Texts and Contemporary Worlds, 5.2 (2009) 233-249.