By Paul Chaffee

DISCERNING THE INSTITUTIONAL SHADOW

Carl Gustaf Jung

Carl Jung’s metaphor of the ‘shadow’ points to the parts of ourselves we don’t like, the feelings and behavior that we repress and hide from, projecting just such behavior on others. If we apply the metaphor to religion, perhaps the best measure and summary of its corporate shadow concerns its relationship to violence and nonviolence. Good and evil are the traditional terms, but they are comparatively abstract and come with all sorts of definitions. The relationship of nonviolence to violence is clearer, though still opaque when we miss the violent implications in otherwise good intentions, a sign of the shadow.

Sadly enough, over the centuries most faith traditions (as well as secular meaning-making traditions such as communism and fascism) have been intimately involved with violence in its various guises. This happens in religious communities regardless of their root values, such as peace, love, and the image of God in all human beings – a lack of discernment that exemplifies religion’s shadow-side.

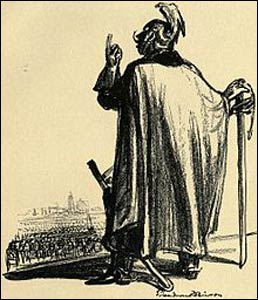

"I Believe in the Sword and Almighty God" (1914) by Boardman Robinson – Photo: WikipediaThis

frightening frailty can come mixed with all sorts of goodness, with communities being nurtured, sacred space and ceremony offered, and comfort and wisdom often provided. Just to say, though: violence seems to pop up periodically, within us and among us, within communities and between communities. One of the great assignments of the spiritual journey is becoming conscious of the unconscious violence that can lurk within and finding the means to turn that energy from the dark to the light, from violence to nonviolence. Both personally and corporately.

The casual conversation about whether “religion is the cause of violence or a victim of those who misuse and abuse it, or, alternatively, a resource for the good,” is usually fraught with misinformation and oversimplification, belying any easy consensus on the matter. In fact, though, over the past 30 years the study of religion and violence has become a burgeoning academic arena, and the religious community-at-large needs to know more about what has been learned.

Studying Religion and Violence

Surveying the study of religion and violence, you find a wide variety of issues and opinions, different definitions and assumptions and judgments. Part of the confusion derives from the impossibility, finally, to divide religious thought and behavior from all the other arenas where we live, a difficulty which opens the door to radically different perspectives on the nature of religion. A minority of scholars think religion is largely the wrapping paper for political, economic institutions with an aggressive agenda. They assume that the power brokers, the politicians and bankers, co-op religion to justify their agenda. Many others, though, see religious institutions and leaders as the source of religiously motivated violence, though most conspicuously in the ‘fundamentalist’ or rigidly exclusivistic expressions of any given tradition or community. A subset of the discipline brings psychoanalysis to bear on the subject, particularly to seriously insane religious leaders like the mass-suicide pastor, Jim Jones.

The complexities of all this analysis is summarized well by R. Scott Appleby in “Religious Violence: The Strong, the Weak, and the Pathological,” a 25-page overview you can download. Appleby suggests “that there is such a thing as religion and that under certain circumstances religions incite or legitimate deadly violence. Yet the relationship between religions, religious actors, and violence is much more complex than that.”

Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence (3rd Ed., 2003) by Mark Juergensmeyer, a sociologist of religion at University of California (Santa Cruz), caught the public’s attention with its detailed narrative and analysis of religious violence, starting with stories of the religious madness instigated by contemporary figures cloaked in religion, including the founder of Aum Shinrikyo (a ‘Buddhist’ sect which carried out a Sarin gas attack in Tokyo subways), the assassin of Yitzsath Rabin, and Timothy McVeigh.

In a 10-page essay in Hedgehog Review (2004) titled “Is Religion the Problem?” Juergensmeyer summarizes his position. His answer, given all the complexities of the subject: “I do not think that religion is the problem. But I do think that the involvement of religion in public life is often problematic.” Almost always, the problematic concerns some sort of ‘justified’ violence, often couched in terms of “cosmic war.”

Juergensmeyer notes, “What makes religious violence particularly savage and relentless is that its perpetrators have placed such religious images of divine struggle – cosmic war – in the service of worldly political battles … The notion of cosmic war gives an all-encompassing world view to those who embrace it.” It absolutizes the conflict, demonizes opponents, holds out for total victory, and embraces vast timelines. The latest example of this thirst for an ultimate battle came in a Reuters headline this month reading “Apocalyptic prophecies drive both sides to Syrian battle for end of time.”

The hard truth is that religions grounded in peace, love, and compassion get appropriated every day to justify the monstrously violent. The shadow reigns wherever that happens, and the complicated task of religious peacemaking is left to somehow shine the light and transform the violence with nonviolence.

We’re not doing well at that. Religious violence is increasing. In January, Pew Research published a report titled “Religious Hostilities Reach Six-Year High,” which begins this way:

The share of countries with a high or very high level of social hostilities involving religion reached a six-year peak in 2012, according to a new study by the Pew Research Center. A third (33%) of the 198 countries and territories included in the study had high religious hostilities in 2012, up from 29% in 2011 and 20% as of mid-2007. Religious hostilities increased in every major region of the world except the Americas. The sharpest increase was in the Middle East and North Africa, which still is feeling the effects of the 2010-11 political uprisings known as the Arab Spring. There also was a significant increase in religious hostilities in the Asia-Pacific region, where China edged into the “high” category for the first time.

Seeking the Light

Less this all seem too dark, Juergensmeyer, like many of his colleagues, holds out hope for humankind and religious peacemaking. His Hedgehog Review essay ends with these words: “Though religion can be a problematic partner in confrontation it also holds the potential of providing a higher vision of human interaction than is portrayed in the bloody encounters of the present.” Earlier in the essay he notes that “religion can also bring more positive elements to a situation of conflict…

It can offer images of a peaceful resolution, justifications for tolerating differences, and a respect for the dignity of all life. It was these images and arguments that brought Hindu values into the notion of satyagraha, or “truth force,” the idea of conflict resolution advocated by Mohandas Gandhi. Similar concepts from Christianity informed the insights of the American theologian, Reinhold Niebuhr, who advocated countervailing power and the institutions of justice as peaceful ways of countering social evil. Niebuhr and Gandhi both influenced the thinking behind the nonviolent struggle of the American civil rights leader, Martin Luther King, Jr.

Last month saw the release of the film Noah, discussed as “the first apocalypse story.” (In fact, Ingrid Lilly points out that the biblical version of the flood was hardly the first.) For Abrahamic traditions, though, the story of the flood is the first foray into the notion of a cosmic struggle where God’s forces win, but most creatures, human and otherwise, perish.

What I found most moving in the film was the enormous grief Noah suffers for his role in the mass genocide, a grief that nearly leads him to compound the tragedy. The Sunday school version (for me) was about the miracle of the ark’s inhabitants surviving; the death of all else that lived was not considered – again, a good example of the shadow in our midst.