Editorial

In spite of its highest aspirations, religion, including its manifold institutions and leaders, is as vulnerable to evil and corruption as any other institution or leader. It’s in the news every day, a priest’s abuse, a cardinal’s misuse of power, a pastor’s greed, a rabbi’s bigotry, an imam’s call for violence. Or, if we look globally, we discover Christians and Muslims killing each other in Nigeria. While being oppressed in Tibet, Buddhists are fighting Muslims in Thailand, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar. Catholics versus Protestants in Ireland, Sunni versus Shia throughout Islam, Orthodox versus Reformed in Judaism. The Middle East, the ‘holy land,’ is a mess of conflict, religious and otherwise. One begins to understand why atheists rail against religion.

Yet all this darkness and more comes from traditions which brought us the wisdom of the prophets, the Beatitudes, the Dhamapada and Bhagavad Gita, the poems of Rumi, saints like Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr., and so much more. These religious, spiritual traditions, through their teachers and wisest leaders, have taught us to care for each other, to reach across to ‘the other’ with compassion and a hospitable heart, to treat the Earth as a member of the family deserving our love and care, to heal the sick and protect the weakest, to forgive each other over and over again, and to reach out to promote life and goodness, justice and compassion.

The terrible irony of this mixture of darkness and the light is as personal as it is universal. What some call original sin others might call the complexities of the ego. The ego worshiping itself is an equal opportunity invader. Even saints have their foibles and breakdowns. Regardless of ‘masters’ deemed ‘perfect’ by their followers, it seems that being human entails contending with impulses deep within ourselves which are destructive as well as constructive. Living into that perplexing dichotomy is an agendum in every spiritual journey.

Carl Jung, early last century, provided a powerful metaphor about how this goodness/badness combination works in us. He suggested that what we don’t want to admit about ourselves, we repress and suppress and imagine in someone else. This unknown, subconscious part of us Jung calls the ‘shadow.’ What we hide from, we project onto some ‘other’ person(s), so that our perception of them has less to do with ‘who they are’ than with ‘my lens’ in looking at them. Deepak Chopra, whether you like him or not, has a splendid three-minute sermonette that nails how we project on others what we dislike in ourselves, the problems that creates, and how to “ameliorate” them. He also addresses the terrors of “the collective shadow” and the resources we have to address it.

This month’s TIO explores those resources and how they can be brought to bear in unbearable circumstances. The work is dangerous and particularly difficult because, by definition, we can’t see the shadow – it is the part of me or of us that we don’t discern without meditation, self-examination, letting go of defensiveness, and nurturing the core values that inspire what is best in our traditions. The articles we’ve collected explore these tools and how people have used them to subdue violence with nonviolence. They are about leaders and institutions, but they also reach into every one of our lives and local communities.

This month’s TIO explores those resources and how they can be brought to bear in unbearable circumstances. The work is dangerous and particularly difficult because, by definition, we can’t see the shadow – it is the part of me or of us that we don’t discern without meditation, self-examination, letting go of defensiveness, and nurturing the core values that inspire what is best in our traditions. The articles we’ve collected explore these tools and how people have used them to subdue violence with nonviolence. They are about leaders and institutions, but they also reach into every one of our lives and local communities.

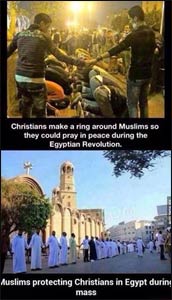

Tehreek Taraque E Insaniat (“Development Action for Mobilization and Emancipation”) is a small United Religions Initiative affiliated interfaith group in Lahore, Pakistan. Their young people have given themselves a special assignment – collecting and circulating pictures of peacemaking, like the Egyptian Christians, on the left, protecting Muslims gathered for peace prayers, as well as Muslims protecting worshiping Christians in Egypt. Promoting peace this graphically in the midst of Pakistan’s current sectarian violence requires a personal grit that might challenge most of us. But the work in Lahore and in our own communities is the same.

Whether you read through this issue now or later, prepare yourself for the exploration by listening to BK Sister Elizabeth’s remarkable musical gift, which introduces TIO’s collection of stories.