In Memoriam

by Ruth Broyde Sharone

. . . As we explore the deep structure of our own traditions, revealing the basic functionality beneath the specific wrappings, we cannot ignore their similarity to those of every other religious and spiritual tradition on the planet. Providence, as well as our own evolutionary perspective, demands that we acknowledge a similar sacred purpose at work in these deep structures, that we learn how others use them for the fulfillment of the Greater Purpose, and how others can aid us in understanding our own use of them.

- From Foundations of the Fourth Turning of Hasidism: A Manifesto, Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi’s final book, coauthored by Netanel Miles-Yépez.

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, 89, died this past July 3. Ordained as an Orthodox rabbi in 1947, he went on to become the founder of Jewish Renewal and a champion of interfaith relations and collaboration. He was well known for his mystical perspective, liturgical innovations, explorations of Hasidism, and interfaith engagement. In over a dozen books he championed the practice of spiritual direction and supported the Gaia hypothesis, ecology, feminism, and the LGBTQ community. Greatly loved as a teacher, he held emeriti professorships at Naropa University and Temple University. His close friendships included the Dalai Lama, Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, Matthew Fox, Thomas Merton, Bernie Glassman, Swami Satchidananda, and Ram Dass.

Reb Zalman was TIO Correspondent Ruth Broyde Sharone’s “rebbe” and mentor.

* * *

Reb Zalman was full of surprises. He kept everyone on their toes, within his own Jewish community and in the interfaith community as well. In the mid-70s Reb Zalman was initiated into Sufism by Pir Vilayat Inayat Khan, leader of the Sufi Order International. In 1989 he was invited to Dharamsala with a group of rabbis to advise H.H. the Dalai Lama – the leader of the exiled Tibetans from China — about how a community in exile can remain strong and vibrant.

In 1995 Reb Zalman accepted the World Wisdom Chair at Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado, the only accredited, Buddhist-inspired university in the Western hemisphere.

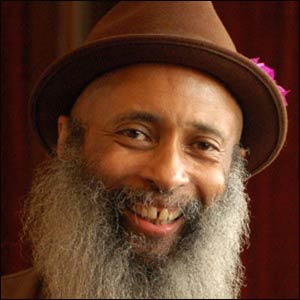

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi in 2005 – Photo: Wikipedia

In 2004 he helped create the first Sufi-Hasidic hybrid order of its kind. His co-writer and collaborator, Natanel Miles-Yépez, notes, “he co-founded the Inayati-Maimuni lineage of Sufism, reviving the medieval tradition of Rabbi Avraham Maimuni and allowing the Hasidic lineage of the Ba’al Shem Tov to integrate with the Sufi lineage of Hazrat Inayat Khan.”

Reb Zalman was an interfaith champion to his bone marrow and sought out interfaith dialogue because of his openness as well as his strong Jewish identity, which always served as an advantage rather than a hindrance. He knew who he was. Judaism was the locus and core of his existence, but it never limited his ability to empathize with others or interface with those who held strong religious beliefs unlike his own – even within his own tradition. It came naturally to him because he was a universalist as well as a Jew. For him there was no conflict.

Once in Calgary, Canada, Reb Zalman participated in a symposium on mysticism with leaders from other traditions. One morning, he writes in First Steps to a New Jewish Spirit, he was praying on the roof of his hotel. Brother Rufus Goodstriker, a medicine man from the Blood Reservation, appeared to conduct his own prayer ritual. Brother Rufus carried his prayer paraphernalia in a colorful striped serape – not too different from the striped prayer shawl the rabbi was wearing. The two nodded in recognition. When both had completed their prayers, Brother Rufus asked Reb Zalman if he could inspect his “prayer instruments.”

Brother Rufus examined them with great respect, asking Reb Zalman to explain the significance of the shofar and the phylacteries he was wearing on his left arm and forehead. Examining the black straps of the phylacteries, he said “Rawhide.” The two regarded each other and nodded in silent recognition.

In the fall of 1992 I had a chance to speak with Reb Zalman about my passion for interfaith. A black woman minister and I had impulsively decided to organize an interfaith pilgrimage to the Middle East, with Jewish, Christian, and Muslim participants, including members of the African-American Strait-Way Church. We would retrace the steps of the Exodus from Cairo to the Sinai desert, then continue to Jerusalem, sharing our faith stories along the way.

“Our goal is to develop trust and friendship across religious and racial boundaries,” I said. Called “Festival of Freedom,” the journey would culminate in a Universal Freedom Seder in Jerusalem during Passover. People of all faiths from all parts of the world would be invited to the festival meal, including Palestinians and Israelis.

“We’d like you to lead the first trip,” I ventured in a hopeful voice.

“You’re meshugah (crazy)!” he declared with a broad grin. Somehow it seemed more like a compliment than an insult, and I nodded my head in assent and smiled.

Then he leaned forward and added, “Don’t worry, because I’m crazy too. And when enough crazy people (meshegoyim) like us get together, we’ll all start to feel sane.” We laughed in unison. Then, to my amazement, he began to draw on the tablecloth the configuration of tables he envisioned for the culminating event. He was hooked!

Rabbi Zalman and the Dalai Lama greet each other in 1997. – Photo: Foto de Vita

So in 1994 he and his partner, Eve Ilsen, came to Jerusalem to offer a Passover workshop for the Festival of Freedom participants as well as local Israelis and Palestinians. I persuaded the Palestinian mayor of Jericho, Rajai Abdo, and his wife to attend the workshop and be guests-of-honor at the culminating event, our Universal Freedom Seder. More than 100 participants filled the room that evening.

No one was prepared for what happened next.

Israeli TV had showed up to document the event for CNN. Just before the Seder officially began, a reporter began doggedly grilling the Muslim mayor, asking provocative political questions. The mayor, distraught, found himself on the hot seat. Suddenly, Reb Zalman rose up from his chair with an aggrieved look on his face. In a tone of righteous indignation, looking like a Biblical prophet in his flowing white robe and long white beard, he chastised the TV journalist.

“The Mayor and his wife are our guests of honor, in our home for dinner, and I take great issue with your line of questioning!” he exclaimed. “This is not the time or the place to debate local politics. We are celebrating a Festival of Freedom.”

Silence reigned. Everyone was shocked. Slowly, the sting of his comment dissipated in the air. The journalist apologized to the mayor and to Reb Zalman. Calm was restored, the mayor and his wife looked reassured, and our Seder activities continued.

Two great teaching moments occurred that evening. First was the importance of creating sacred space to protect your guests and make sure they feel welcome.

The second lesson came later. I saw Reb Zalman make his way over to the cheeky journalist and apologize for his outburst. He was sorry, he said, to embarrass the journalist publicly but felt compelled to protect the guests. Reb Zalman’s sensitivity to his guests reached further to include the outspoken journalist, who accepted the apology. Highlights of the interfaith Seder were later broadcast around the world in a CNN Global News report.

Reb Zalman’s forays into the interfaith arena, internationally and locally, were legion. In recent years, for example, he formed a close partnership with Sheikh Ibrahim Farajaje, provost at the Unitarian Starr King School for the Ministry in Berkeley. They frequently taught together. The Sufi leader knew the Hebrew prayers by heart and would sing them at Jewish Renewal congregations during Sabbath services. The Sheikh’s son would also provide music to accompany those prayers, which he also knew by heart. Reb Zalman would include the azan, the Muslim call to prayer, in a seamless liturgy of melodies that merged, converged, and diverged, paying honor to two great traditions without resorting to syncretism.

Sheikh Ibrahim Farajaje – Photo: Starr King School for the Ministry

I interviewed Reb Zalman and Sheikh Ibrahim in 2012, after they led an experiential workshop. Reb Zalman looked particularly sad, acknowledging that “ecumenism” could be, in his words, “decidedly lonely,” unless you had a strong partnership with a person from another tradition. “Even if you are doing work you believe is absolutely vital to the future of our planet, you need to be cognizant that you are also opening yourself up to criticism from within your own community because of those who fear interfaith engagement will cause their tradition to become diluted and distorted, rather than enhanced by the interchange.”

Sheikh Ibrahim nodded in assent, acknowledging how he also felt the sting of criticism from members of his Muslim community objecting to his partnering with a rabbi.

“That’s why it is so crucial that we do this work together as colleagues and friends,” Reb Zalman underscored. The two men hugged with open affection.

Of the many Reb Zalman interfaith stories, my favorite perfectly demonstrates his uncanny ability to navigate potential minefields.

He was visiting at a conference with a Zen roshi. The roshi asked him, “I need your advice. I have ten students and seven of them are Jewish. What should I say to them?”

Reb Zalman remained quiet, contemplating the monk’s question. Then a twinkle came into his eye as he answered, “Tell them to do what a Jew must do, but to do it with Zen mind.”

Pure Reb Zalman. Zichrono l’vracha – May his memory be blessed.