By Ilona Gerbakher

THE INTERFAITH CONSEQUENCES OF REDISCOVERING YOUR FAITH

The Torah in the Glockengasse Synagogue in Cologne, Germany – Photo: Wikipedia

My friend Jeremy Sher is a brilliant up-and-coming leader of the Reform rabbinical movement. He is working to create a vision of Judaism that is both inclusive and yet deeply spiritually fulfilling, a Judaism which rejects gender discrimination and insularity while embracing and upholding the primacy of the holy texts in Jewish life.

Jeremy lives in Jaffa, the mostly Arab city that abuts Tel Aviv, genially going about the daily business of preparing for ordination, learning Hebrew, and completing a research fellowship while saying “shukran” (“thank you”) to his Arab neighbors and “toda” (“thank you”) to his Jewish neighbors. Jeremy is what it looks like when you have a smart, compassionate, religiously Jewish man who rejects parochial attitudes in favor of an open-minded and open-hearted commitment to tikkun olam, healing the world. You could probably say he’s my religious role model.

Saying that a Jewish rabbinical student is my role model in Israel is bizarre, given my lifelong ambivalence – if not to say outright dislike – of religious Judaism. I left Judaism at the tender, well-considered age of eight, when my rabbi told me that women could marry rabbis, but could not become them. I was sick of the rules and the restrictions, tired of halakha(the intricate Jewish legal code) and tsnius(the modest dress required of religious Jewish women – covered hair upon marriage, skin covered from the knees to the elbows to the collarbones, no tight clothing). I wanted to eat pepperoni pizza and watch Saturday-morning cartoons like all the other American kids: strictly speaking, Jews are not allowed to eat pork, to eat meat and cheese at the same time, or use electricity on the Sabbath. I left God, the synagogue, and the Torah, and I never looked back. I remained ‘culturally’ Jewish (whatever on earth that means) and would call myself Jewish when asked my religion. But for all intents and purposes I was an atheist and a self-hating Jew.

But after 20 years of apostasy, this prodigal child has returned to the faith of her forefathers, fascinated by a complex textual tradition which has united a people from time immemorial. Why did I come back, after so many years astray? A big part of it was the time I spent in Morocco, worshipping in the Sephardic synagogue of Fez, feeling for once at home in my skin and in my ritual. (Sephardic Jews usually come from France, Spain, and North Africa, Ashkanzi Jews from Eastern Europe and North America.) Even more important was a conversation I had at the beginning of my studies in Jerusalem with a new friend, an Orthodox Jewish woman who lives just across the hall from my dorm room.

Janet Safford is an unusual woman, a great scholar of the ancient world, fluent in all of the languages and mythologies of the Near East, and an ardent feminist. Over endless cups of coffee, I poured out my hatred of Judaism’s misogyny, my rejection of its hidebound rules, and my frustration with what I saw as the moral failure of the Jewish community to reckon with Palestine, once and for all. She listened with her usual contemplative half-frown, and asked me a simple question: “So what do you plan to do with Judaism? Throw it all out, start something new? Isn’t it more powerful to learn the texts, and change it from within? That’s what I plan to do.”

I was staggered and ashamed of myself. Janet has spent the last five years dedicated to the study of Jewish texts and to the texts that inspired them – in Hebrew, Aramaic, Ugaritic, Hieroglyphic – you name it, this girl knows it, and can quote it to you in the original language. Meanwhile, the last time I had opened a religious Jewish text was when I read a Torah portion at my Bat Mitzvah in 1999. What did I know of the texts and the tradition that I was critiquing? Absolutely nothing.

Finding Renewal

So I rededicated myself to the study of my own tradition, in the original languages of Hebrew and Aramaic. I read the Tanakh, Talmud, and the Zohar, intrigued by the great exegetical flexibility of the Jewish tradition, swimming a sea of text and finding myself buoyed by the joy and relief of a kind of soul-recognition. It is said in the Talmud that an angel whispers the whole of the oral and written Torah into the ear of every Jew at birth, and then kisses them on the lips and they forget. I have spent the last three months remembering these inborn texts, and they fill me with joy. One of my classmates, after a particularly stirring discussion about Midrash, pulled me aside after class and said that my face was glowing, as though I was lit from within.

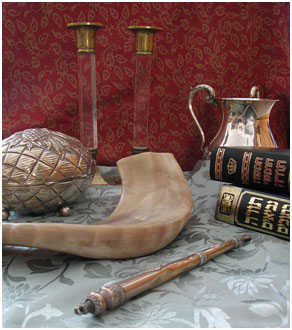

“Judaica” - Shabbat candlesticks, handwashing cup, Chumash and Tanakh, Torah pointer, shofar and etrog box – Photo: Gilabrand, en.wikipedia

These chance encounters, with Jeremy and Janet, have overturned my relationship to my faith, and have filled me with energy and hope. It has been so easy for me to study Islam over the last decade, because I am so removed from it. I find it to be a fascinating tradition, I am in love with the Arabic language, and my time living in Qatar and Morocco were undoubtedly the most formative experiences of my life. But nothing has challenged me intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually as much as the return to the holy books of my forefathers, with their playful poetries and their divisive dialectics.

Becoming re-grounded in Jewish texts and learning Hebrew has also lent an added strength to my interfaith advocacy. As any Jewish advocate will tell you, the number one attack on heterodox Jewish speech is being called a “self-hating Jew.” You support the Palestinian right to a state? You’re a self- hating Jew! You don’t think all Arabs are terrorists? You’re a self-hating Jew! You study Arabic? You’re a self-hating Jew! It’s the Jewish equivalent of calling a girl a slut, and it is very effective in quieting oppositional discourse – especially because so many Jews who do have heterodox opinions know little to nothing about Jewish texts.

Nothing quiets the slur-hurlers more quickly than the ability to quote Tanakh in Hebrew, or a detailed fifteen-minute discussion of an obscure Mishnaic passage about what to do when you find a lost cow on your porch. Knowing the texts, the traditions, and the language just a little bit, makes it that much harder for religious Jews to dismiss me and my opinions about Islam, Muslims, and the need for an extensive Jewish commitment to the interfaith movement.

I recently spent a weekend with an Israeli family with very hardened, negative attitudes about Arabs – at least on the surface of things. My first meeting with them, at a wedding in California, nearly ended in tears when I was told that all Arabs are terrorists and that I was a fool for thinking otherwise. This was before moving to Israel, learning Hebrew, or studying Jewish texts. But being able to discuss the weekly Torah reading in my rudimentary Hebrew disarmed these prickly Sabras, and we ended the weekend with me teaching them Arabic pronunciation and with them promising to visit me in Morocco!

Chance encounters, answered questions, exegetical debates in foreign tongues – these are the drops of hope and connection that fill my cup of hope. Little by little, by learning languages, studying texts, and traveling the length and breadth of my two religious worlds, I’m having the conversations that change attitudes and soften prejudices. But this is only the beginning. As I learn more about Judaism, as I work more with religious Jews, and as my time in Jerusalem continues, I am optimistic that I will build more bridges, share more stories, and change more minds. I close with my favorite words in both traditions: Shalom Aleichem. Salaam Aleykum. May peace be with you all.