By Katherine Marshall

“THE CONFERENCE OF THE BIRDS” AND OUR LIVES

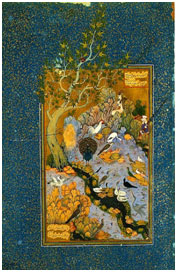

A scene from”The Conference of the Birds”in a Persian miniature. – Photo: Wikipedia

A band of birds of different species sets out on a perilous journey through the unknown, in search of their king. That is the story of The Conference of the Birds, the 12th century masterpiece of Persian poet Farid ud-Din Attar. Like Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, it offers an amalgam of myths and vignettes of daily life, tales of courage and divine inspiration, and silly, telling stories. It is a parable of humankind’s spiritual quest and life’s journey.

The annual FesFestival of World Sacred Music, which celebrated its twentieth birthday in 2014, took the Conference of the Birds as its centerpiece. The idea was to explore religious and cultural diversity through the allegory of the journey of the birds. Each member of the band of birds represented a different human type, saintly and querulous, brave and foolish. They travel through a series of seven valleys (in the poem, searching for love, understanding, independence and detachment, unity, astonishment, and finally poverty and nothingness)

These valleys, in the festival’s opening operatic spectacle this year, each represent one of the world’s great religious and cultural traditions. When the brave survivors reach the Simorgh, the king they have been seeking, they look and see, as in a mirror, themselves. The search for truth, for God, for a king, and for the answer to living together must begin with a searching exploration of the self. Only there can the answers be found.

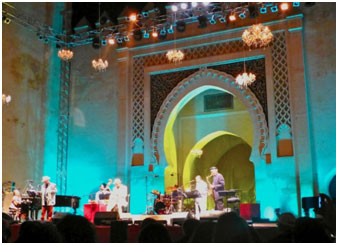

Fes at dusk. – Photo: Omar Chennaf

The Fes Festival was launched in Morocco not long after the 1991 Gulf War, as a deliberate effort to bridge the divides that threatened to polarize “the West” and “Islam.” Drawing on the history of Fes, a city that describes itself as Morocco’s spiritual capital and prides itself on ancient Muslim and Jewish populations living side by side, the festival brings together music and other art forms from all parts of the world. It is an expression of tolerance, but, still more, a celebration of difference.

The Fes Festival has grown into a renowned world music event, drawing exuberant crowds from Europe and beyond. The theme is sacred music, and classic Christian, Jewish, and Sufi music is part of the program. But so are performances, like that of South African Johnny Clegg and Senegalese Youssou N’dour and a delightful Irish group, the Atlan Ensemble, that bring audiences to their feet, clapping, shouting, and dancing. Diversity is of the essence, both in the artistic expression and in the dress and comportment of the audience.

That is the living expression of the festival’s message: a love of difference and a faith that together different melodies and rhythms can bring harmony without compromising the essence of any part. In less poetic language, the hope is that by coming to know and enjoy the musical expressions of different religions and cultures, people will understand and appreciate each other. And stop fighting.

A session of the Fes Forum 2014 – Photo: Omar Chenaffi

Beyond the music, films, art exhibits, and craft workshops, a further part of the festival is a five-day intellectual Forum. The goal is framed as “giving globalization a soul,” one that might be termed bold, visionary, or fanciful. Each morning a group that includes politicians, religious leaders, businessmen, journalists, artists, and so forth, tackles a different topic. This year the menu included Mandela’s legacy, pluralism as a challenge for Morocco and Europe, and the Israel Palestine conflict. The hope is that in the setting of Fes, softened by music, inspired by the tangible beauty of artistic expression, tired ideas and stale debates will fade and new ideas and true dialogue will emerge.

The Forum has yet to achieve its ambitious goal of resetting the tone of global encounters and generating ideas that truly promise to address the world’s problems. The ambition is bold but not unattainable: in a setting outside cold conference halls, alongside artistic genius and beauty, in a country between tradition and modernity, between Africa and Europe, miracles might be achieved, though the inspiration of Sufi mysticism, a spiritual backdrop, and artistic genius could also do with some fairly rigorous planning and adequate resources. As a Forum veteran, I live in hope.

Gospel and blues at Fes 2014 – Photo: Katherine Marshall

The festival, the poem, The Conference of the Birds, and the open discussions at the Fes Forum offer an antidote to poisonous, violent images of conflict in the Middle East and beyond, and of extremist Islam. At one level there was an eerie quality in hearing repeated expressions of Islam as love (then seeing images of Iraq and Syria on a computer screen), and to see the “Valley of Islam” equated with unity, when Sunni-Shia divides seem deeper than ever. Yet the lived experience of Sufi and moderate Islam are a reality for a great majority of Muslims. The messages of diversity, tolerance, and appreciation of difference are both ancient and modern. They are a balm and they are real. The notion of living together is not a danger to be managed nor an unattainable dream. It is within reach.

This article was originally published in the Huffington Post, June 24, 2014.