By Vicki Garlock

LEARNING TO BE STILL

“It’s important for all of us to learn to be still… Really, it’s better to learn as a child.”

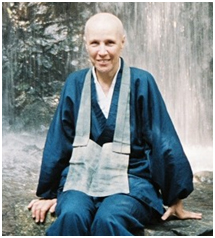

– Rev. Teijo Munnich, Great Tree Zen Temple

Rev. Teijo Munnich – Photo: Great Tree Temple

The oldest child in the room happened to be my son. He was seven years old at the time. The youngest child was only 4 years old. All the kids, along with a few teachers, were sitting on green meditation cushions arranged in a circle with their eyes closed. Actually, eyes were closed intermittently since there was a fair bit of peeking. “Place a hand on your belly,” she said, “and see if you can feel your breath. When you take a breath in, your belly should move out. When you let your breath go, your belly should move in.”

In and out, in and out, in and out. Slowly. Deliberately. Quietly. The energy in the room became calmer and more serene. The sounds of the babies babbling in the nursery next door seemed louder. The furtive glances stopped as the kids’ eyes fluttered closed and stayed that way. It was obvious that the Reverend Teijo Munnich, ordained Zen priest and founder of Great Tree Zen Temple, had led children in sitting meditations many times before.

As Teijo explained, “The general philosophy people have about children is that they need to move around a lot, but they can learn to be quiet. I went to Catholic schools growing up, and we had to be quiet a lot …We all have quiet inside of us. All this noise and busy-ness is really a cultural overlay. At first, when things get quiet around them, kids don’t know what to do, so they start making noise! But once they get used to the idea, they can definitely quiet down.”

Of course, she was right. In just a few minutes, she had demonstrated exactly that. Teijo usually starts kids off with a 5-minute sitting meditation, which is what she did with our group, since they are not regular meditators. At the Temple, however, she has tweeners who have already been meditating for years. At the annual youth retreat, they sit for 20 minutes at a time. For some of them, the goal is simply to remain on the cushion, but the more experienced kids could sit longer.

Photo: Meditation Initiative

Teijo believes that any number of activities can be meditative. The key is to be quiet and mindful. The kids might fold origami, play a quiet version of Pick-up Sticks, help clean the temple, or engage in deep relaxation exercises. They especially love the bell-ringing practice used routinely in Thich Nhat Hanh’s communities like Plum Village. At Great Tree, a bell is set to ring every 15 minutes. When the bell sounds, everyone stops whatever they are doing and focuses on breathing until the ringing stops. The kids always request the bell.

All this kid meditation, however, is a relatively new thing. Some would argue that it’s also a “Western thing.” Dorje Lopön Dr. Hun Lye, founder of Urban Dharma in Asheville, NC, grew up in a Buddhist family in Malaysia. “As a kid, I didn’t do meditation. The thinking was that … only people with firm spiritual foundations should engage in meditation.” He believes the mindfulness movement – or what some have called the mass marketing of Buddhism in America – underlies these attitudinal differences. “Meditation is viewed not as a means to contact the supernatural or the divine, but as an effective tool for navigating a stressful life. Parents are all for it. They see it as a way for their kids to manage their emotions, to focus better, and to be more effective students.”

A Transforming Practice

Such “mindfulness” programs are everywhere these days. Mindful Schools, for example, teaches adults the fundamentals of mindfulness and also trains teachers to share mindfulness practices with kids and adolescents. They claim to have reached over 300,000 kids. Peace in Schools focuses on teens. In the fall of 2014, they announced the establishment of the first for-credit mindfulness class in an American public high school. The Mindfulness in Schools Project, based in the UK, offers separate training sessions for those who work with 7-11-year-olds or 11-18-year-olds. The Vancouver School Board in Canada has adopted the Mind UP program, and the Meditation Initiative offers free meditation for people of all ages and walks of life. Regardless of market niche or carefully chosen terminology, these programs are nearly identical in scope and mission.

Students meditate during Suicide Prevention Week at Torrey Pines High School in San Diego, CA. – Photo: Meditation Initiative

Whatever you call it, kids can clearly do it. Moreover, recent research findings suggest that these practices may, in fact, produce the effects desired by parents, teachers, and the students themselves. In one study, low-income, ethnic-minority elementary students in California showed increases in self-control, classroom participation, respecting others, and paying attention following a five-week, 3x-per-week mindfulness program.

In another study, 35 students attending an alternative high school engaged in mindfulness meditation over an 8-week period. Perceived benefits included improved self-awareness, emotional coping, and ability to pay attention. Stress relief and improved school climate were rated as particularly important outcomes. Similar results were reported in the UK where more than 250 students in six schools participated in a mindfulness program during the first term of the calendar year. Those students reported fewer depressive symptoms, lower stress, and greater well-being when compared to a similar number of students in matched schools without the program.

But is it Buddhist?

A major issue nowadays centers on the extent to which the widespread mindfulness/meditation seen in places like the U.S. and the UK is associated with the tenets of Buddhism. In some cases it is. In other cases, clearly it is not. In some instances, the language has almost certainly been changed to make meditation more secular, less religious, and therefore more palatable to public schools. In other instances, meditation serves as the gateway to more traditional Buddhist teachings. Buddhist scholars decry the rise of “nightstand Buddhists” and mourn the co-opting of meditation by capitalism, but the vast majority of self-identifying Buddhists in the world don’t really seem to care. Wary Christians wonder why the U.S. Supreme Court refuses to treat these programs as another version of “prayer in schools,” but classroom instructors find little to complain about when it comes to results.

In some ways, meditation/mindfulness is a victim of its own beauty and simplicity. It requires no equipment, no money, and for many practitioners, only a small amount of time. It can be done at any age, at a moment’s notice, and with any number of different techniques. And therein lies the problem. If everyone everywhere is doing it, that raises concerns about the lack of standardization, the loss of historical roots, and the “watering down” of the practice. But if the practice is reserved for only a special few, then the world risks being deprived of its potential benefits.

After our brief sitting meditation with Teijo, all the kids made Mindfulness Globes. We filled empty baby-food jars with a carefully-developed recipe of water, oil, and glitter. We shook them and watched the glitter spin around in the jar, a visual representation of our busy minds. Then, we watched as the glitter slowly floated downward. All eyes were on the jars. No one was talking. Everyone’s breathing became slower and deeper. You could hear a pin drop. And we realized that, unbeknownst to us, Teijo has just gotten all of us to meditate again. At least according to some definitions.

Getting Started with Your Kids

Regardless of your take on the issue, you probably don’t need a course to get started. There are plenty of books, web sites, and on-line videos to assist you.

Books

Worry-Free Tree: Bedtime Meditations for Children Aged 4-8 Years by Suzie St. George and Fiona McDougall (Tablo Publishing, 2015)

Moonbeam: A Book of Meditations for Children by Maureen Garth (Harper Collins, 2011)

Relax Kids: Pants of Peace: 52 Meditation Tools for Children by Marneta Viegas (Our Street Books, 2015)

Meditation Is an Open Sky: Mindfulness for Kids by Whitney Stewart and Sally Rippin (Albert Whitman & Co., 2015)

Meditation, My Friend: Meditation for Kids and Beginners of all Ages by Betsy Thomson (Author) and Mitchell Hoffsteader (Contributor) (Betsy Thomson, 2013)

Audio Recordings

Bedtime Meditations for Kids by Christiane Kerr (Diviniti Publishing, 2006)

Enchanted Meditations for Kids by Christiane Kerr (Diviniti Publishing, 2006)

Bedtime: Guided Meditations for Children by Michelle Roberton-Jones (Paradise Music, 2013)

How-To Web Sites

Four Ways to Start Kids Meditating

Five Tips to Teach Children Mindfulness and Meditation

Belly Breathing with Your Kids

You Tube Videos

There are many how-to-meditate videos on line. These links are for guided meditations appropriate for children. The last one is probably better for slightly older children.

Kathy Kruger’s Clouds and Rain Children’s Meditation