By Vicki Garlock

INTERFAITH'S MOST POWERFUL TOOL

Even the silliest folk tale taps into what we are as spiritual beings. We step into a magical space, share our hearts … and connect as beautiful creatures of God’s creation.

– Pam Faro

Everyone loves a story. A child, recently-bathed with teeth brushed and damp hair drying into awkward tufts on a bedtime pillow … a professional, dressed in business casual at a boring conference presentation in a midtown hotel … an aging parent, lying in a nursing home bed no longer able to walk easily or remember the date. Age, disposition, and the surrounding context are irrelevant. Human brains perk up as soon as a narrative begins. Stories fascinate and engage, transcending time and place in way few other mediums can. Maybe this is why myths and legends hold such a special place in all faith traditions and why story-sharing has become an important component of multifaith exploration.

Pam Faro has been sharing tales on the world stage for more than a quarter century. She performs stories, weaves tales, and helps others incorporate story into their lives and professions. Her repertoire ranges from the ancient to the modern, and she performs stories from every continent. She offers school assemblies, in-service trainings, keynote addresses, workshops, and sermons. She has also led storytelling workshops for school teachers, ministers, and kids of all ages. In the storytelling world, Pam does it all. So, no surprise, her work is grounded in an interfaith perspective.

She began her studies at Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado on September 10, 2001 – the day before the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Her entire seminary experience immediately became steeped in the aftermath of the attacks themselves. The motivations for the attacks became fulcrum points for discussion, exploration, inquiry, and discernment.

Inspired by Ramon Llull

Ramon Llull (1232-1316) was a Franciscan writer, poet, theologian, mystic, mathematician, cosmologist, and logician. Once considered a heretic, he was beatified in 1857 by Pope Pius IX. – Photo: Wikipedia

In her final quarter of coursework, Pam Faro enrolled in a class called Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Medieval Spain. In that era, particularly in the south, people from all three faith traditions lived in close proximity, and interactions were generally amicable. Pam was especially intrigued by The Book of the Gentileand theThree Wise Men written in the 13th century by Ramon Llull (English translations of his work usually spell his name Raymond Lully.) A member of the Franciscan order and a philosopher, Llull authored over 260 works and was committed to converting both Jews and Muslims to the Christian faith. However, The Book of the Gentile and the Three Wise Men is known for its deep reverence of all three Abrahamic religions and its open-minded conclusion, rarities in the corpus of polemical works of the time.

In the story, a Gentile (read: Pagan), is wandering in a forest in deep despair. He meets three “wise men” – a Jew, a Christian, and a Muslim. The Pagan asks each of them to explain the tenets of their respective faiths. They do this with the utmost respect for one another. In the end, the Pagan expresses his gratitude and displays a clear understanding of what each man offered. But the wise men never ask the Pagan which approach he has chosen as the best. Instead, they agree that each man should be free to choose his own religion and that future debate and dialogue require ignorance on the Pagan’s final selection. The story clearly reflects Llull’s knowledge of the three monotheistic religions, and centuries later, it continues to offer a model for interfaith dialogue.

The ancient story serves as the foundation for Pam’s Andalusian Trilogy program in which she shares stories, poetry, and songs from the three faith traditions. She has performed the trilogy in both Christian and interfaith settings where it always fosters an appreciation for hearing and telling narratives that lie outside of our traditional comfort zones.

Branching Out

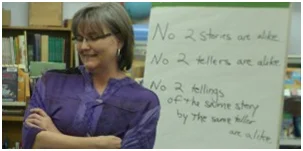

Pam Faro as a story-teller

Since developing the Andalusian Trilogy, Pam has enhanced her interfaith repertoire with stories from the Hindu, Baha’i, and Buddhist traditions. These tales complement her already extensive, and still growing, collection of stories from indigenous communities. Even within the Christian tradition, Pam encourages a bit of boundary-pushing. In her program, “Women on the Way,” created by New Testament scholar Joanna Dewey, she tells stories from the Gospel of Mark from the perspective and experience of a first century woman who followed Jesus. As Pam puts it, “We’re having interfaith challenges planet-wide and certainly in the U.S. I love to find ways to bridge divides – whether those divides arise from ignorance, incorrect assumptions, or real differences – through story. Stories are where we meet.”

Scholars and scientists who research storytelling seem to agree. According to Brian Boyd, author of On the Origins of Stories (2009), storytelling and the creation of narrative are integral aspects of being human. Stories can focus attention, highlight our commonalities, and promote social cohesion – all of which are evolutionarily advantageous. Neuroscientists are also catching the storytelling spirit. Studies using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) techniques look at brain areas activated when people listen to a story.

The data show that different brain regions are activated by different aspects of a narrative. For example, when a character’s goals change, the prefrontal cortex – an area known to be involved in real-life goal-directed behavior – shows increased activation. Similarly, when a fictional character interacts with a new object in a story, brain regions associated with hand representation and real-life grasping show increased activation.

When Kids Become Story-tellers

Although most research is still being done in adults, everyone knows that kids love stories. Educators, librarians, publishers, and authors regularly tout the benefits of reading to children from an early age, but a few people have also recognized the importance of kids, themselves, being storytellers.

Over the years, Pam has developed engaging methods to help kids tell their own stories. She always begins by modeling storytelling, and she often ends with some sort of presentation for the adults, but what happens in between is the most important. She asks kids to choose either a favorite place or a familiar story. Through exercises and games, she then invites them, not just to envision the story, but to smell the story, to feel the story, and to hear the story. That inner imagining is then translated into an outward expression of voice and movement.

Pam Faro as a teacher

What would the characters say? How would they act? What would the characters do and why would they do it? Once those questions are answered, the focus moves to the breath. As Pam explains, “It is the breath that powers your voice and your body and your brain. And we all know how important the breath is to spirit.” And there lies the richness of any storytelling experience: it comes from the spirit, it engages the spirit, and then it re-energizes the spirit.

Storytelling is widely regarded as a powerful interfaith tool. In many cases, if not most, this storytelling occurs when grown-ups share stories about their own particular faith journeys – a practice grounded in the assumption that “it’s impossible to hate ‘the other’ once you’ve heard their stories.” This approach is somewhat limiting, however, when it comes to the interfaith education of kids. Faith journeys are somewhat abstract by their very nature, and kids’ journeys are still in the infancy stages.

However, the world’s faith traditions are full of mythical tales and legends that kids love. Those of us interested in interfaith education need to begin sharing stories from the various faith traditions beginning at an early age. Many of these stories share common themes – share, don’t lie, be nice, control your anger – that caregivers the world over want their kids to embody. The stories make kids laugh, cry, gasp, and giggle. They touch the spirit. Just ask Pam Faro.

To find out more about Pam’s repertoire and how she might bring storytelling to you, check out www.storycrossings.com.