"We are All God's Children"

The Interfaith Legacy of Guru Nanak

by Marcus Braybrooke

An overwhelming sense of the Glory and Oneness of God made Guru Nanak (1469-1539), the founder of Sikhism, impatient with religious divisions, doctrines, and rituals. This sense of the Oneness of God is for me at the very heart of the interfaith journey. There are many practical reasons why interfaith cooperation is vital and as many attempts to find a theological or philosophical justification for it. But to have experienced even a hint of Divine Love is sufficient warrant for Nanak’s claim that

The One God is Parent to all,

We are all God’s children.

In 1969, to mark the 500th centenary of Guru Nanak’s birth, a conference was held at the Punjabi University in Patiala at the dedication of the Guru Gobind Singh Bahavan, a magnificent meeting building designed to symbolize spiritual unity. It was the first international conference that I attended. In the heat, we listened to scholarly papers arguing whether Guru Nanak had borrowed more from the Hindu bhakti or devotional tradition or from Islam, especially Sufism. It was similar to the way some scholars try to dissect the sources that the Prophet Muhammad used to create the Qur’an.

The Guru Gobind Bhagwan Bahavan at Punjabi University – Photo: Rohit Markande, Cc.3.0

I felt the academic discussion missed the point that Guru Nanak’s witness flowed from a personal experience of Divine Grace – and in my paper I compared his experience to that of Sir Francis Younghusband, the founder of the World Congress of Faiths.

That conference devoted to Guru Nanak explains, perhaps, his lasting influence on me. Though born to Hindu parents, he rejected the polarization of Hindus and Muslims. As he emerged from his first deep communion with the Divine, he said,

There is no Hindu:

There is no Muslim.

Nanak also regarded ritual as meaningless unless it led to inner purification. When, aged 11, it was time for him to wear the Hindu sacred thread, he asked the Brahmin priest what difference it would make. Was it not righteous deeds, Nanak asked, that distinguished one person from another? Not getting a satisfactory answer, Nanak refused to wear the thread and recited a verse he had composed:

A fresco portraying Guru Nanak – Wikimedia, public domain

Out of the cotton of compassion

Spin the thread of contentment,

Tie the knot of continence,

And the twist of virtue;

Make such a sacred thread;

O Pundit, for your inner self.

Later he was to say:

Pollution of the mind is greed,

The pollution of the tongue lying,

The pollution of the eyes is to look with covetousness

Upon another’s wealth, upon another’s wife…,

The pollution of the ears is to listen to slander.

Visiting Mecca, Nanak slept with his feet towards the holy Ka’aba. A Muslim woke him and angrily reproved him for this profanity. Nanak replied, “Turn my feet to any direction where God is not present.” He stressed inner holiness. To Muslims he said,

Make mercy your mosque and faith your prayer mat,

Righteousness your Qur’an;

Modesty your circumcising, goodness your fasting,

For thus the true Muslim expresses his faith.

Although Guru Nanak spent many years travelling, he rejected the asceticism of the wandering Sadhu. Instead, he advocated a willing and joyous acceptance of life. “The body is the palace, the temple, the house of God: into it He has put His eternal light.” Liberation was to be won in the world, “amid its laughter and sport, fineries and food.” He saw a divine purpose in family life: Living in “in the midst of wife and children one would gain liberation.”

He stressed the importance of service of others. “By a life of service in this world alone will one become entitled to a seat in the next.” “There can be no love of God without service.” In the community that he established in Kartarpur, he settled in about 1521, after his travels, and stayed for the rest of his life. Everyone was expected to work as well as join in the daily regimen of bathing, eating together, and singing hymns (bhajans). He said, “They alone who live by their own labour and share its fruit with others have found the right path.”

Because the world was God’s creation, Nanak was deeply concerned about social and economic problems of the time. He attacked the rampant corruption and abuse of power. “The times are like a drawn knife… And righteousness hath fled on wings.” He criticized rulers and complained that religion was mostly formal and often hypocritical. “Those who wear the sacred thread use knives to cut men’s throats.” Indeed, although Nanak repeatedly spoke of God’s power and justice, he did once ask, “When there was such suffering, did you not feel pity, O God? Creator, you are the same for all.”

Nanak was disgusted by the treatment of women as inferior. He rejected the view, common at the time, that menstruation and childbirth were defiling. Among Guru Nanak’s followers, women were treated equally.

Of woman we are born, of woman conceived,

To woman engaged, to woman married

… By woman is the civilization continued…

Then why call her evil from whom are great men born?...

And without woman none should exist.

The Founding of Sikhism

It is perhaps paradoxical that someone who objected to religious labels should form his own community, the Sikhs. Yet however universalist we may be, we cannot escape our particularity. I wonder whether ‘not religious but spiritual’ will become a distinct tradition. In Britain there is already a One Spirit Alliance working “to promote and provide a forum for spiritually-minded people, organisations, and networks to foster connection and collaboration between them.”

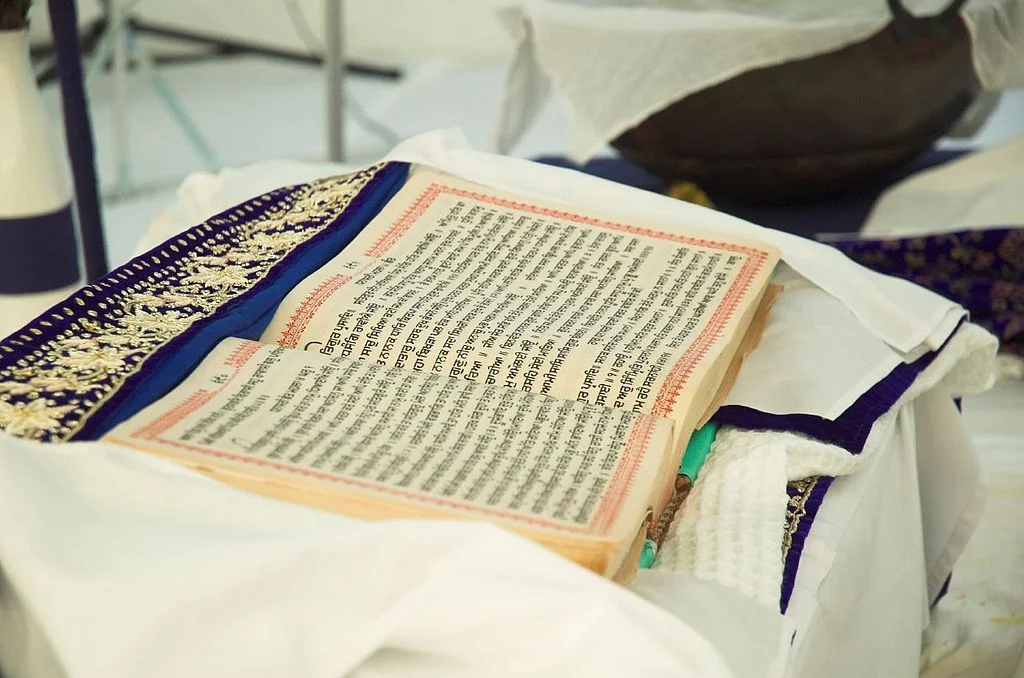

To ensure that his followers preserved his teachings, Nanak appointed a successor, although by not choosing a son, he avoided creating a dynasty. Angad Dev (1504-1552) became the Second Guru. There were eight further Sikh Gurus. The tenth Guru, Gobind Singh (1666-1708), transferred the Guru’s authority to the community and to their scripture, a collection of devotional hymns called the Guru Granth Sahib and known as the ‘living’ Guru. Gobind Singh also initiated the ‘The Five Beloved Ones’ with sweetened water (amrit), the nectar of immortality. The five were called Singh, and they and others who were initiated, were required to wear five symbols of the Khalsa, all of which began with the letter ‘k’: kes, long hair and a beard; kangha, a comb to keep it tidy; kara, a steel bracelet; kaccha, short breeches; and kirpan, a sword. Their appearance distinguished them from both Muslims and Hindus and gave the Sikhs a visible and separate identity, which strengthened their resistance to persecution and aggression.

Langar was served daily to thousands attending the Barcelona Parliament of the World’s Religions in 2004, a tradition which has continued at Parliament gatherings, most recently in Salt Lake City in 2015. – Photo: SikhiWiki

The langar, the common kitchen at a gurdwara (or place of worship), was introduced by Guru Nanak. Sikhs still witness to the Oneness of God and the unity of the human family by freely feeding whoever comes for worship or simply out of hunger. It is fitting that langar has become the lasting memory and symbol of the Barcelona Parliament of World Religions. Repeated every day around the world, it is a reminder of the loving care and interfaith-friendly attitude Guru Nanak asked from his followers.