The Oldest Inhabited City on Earth

by Ruth Broyde Sharone

“There is hardly any city in the world that can claim greater antiquity, greater continuity, and greater popularity than Banaras (the British name for Varanasi). Banaras has been a holy city for at least 30 centuries. No city in India arouses the emotions of Hindus as much as Kasi does.” (Varanasi’s name in Hindu religious literature)

– Pandurang Vaman Kane, noted Indologist and Sanskrit scholar

If you are a Westerner, the clock stops here in Varanasi, India, the oldest inhabited city on Earth.

Everyday traffic in Varanasi can be intimidating. – Photo: Tristan Savatier

“We’ll reach our hotel in five minutes,” the tour guide reassures our group for the fourth time in an hour, while we look out the windows and contemplate the dizzying traffic jam on all sides. The bulging streets of Varanasi are a maze of cars, vendors, bicycle rickshaws, motor-scooters transporting mothers and fathers and often three children sandwiched in between, fearless pedestrians, ambling cows and barking dogs. And moving timelessly through it all – no matter their status or caste – are the women and young girls who appear on the horizon like exotic princesses in their bright-colored, mirror-embellished saris of vermillion, fuchsia, aquamarine, marigold, emerald, and turquoise.

“Five more minutes,” the tour guide promises again. Some passengers on the bus fret and fidget while others smile and assume their oh-yeah-I’ve-heard-that-before facial expression. Meanwhile the bus driver good-naturedly pumps his horn in sharp, melodious blasts, adding his own contribution to the cacophony of horns, bells, and beeps of the allegro con gusto Varanasi street concert.

An English friend of mine who visited Africa for the first time more than 30 years ago shared one particular experience he found unforgettable. He said it was the “sound” of the profound silence rising at night from the vast tundra of Zimbabwe, expanding as if to encompass the entire world – with only an occasional sigh of wind that rustled the golden carpet of wheat. “I could stand for hours listening to that silence, he said, his voice filled with awe. “It was palpable because until then I never knew what silence sounded like.” By contrast, in India one is assaulted daily by the ear-splitting noises of chaotic, multi-layered, over-populated centers of humanity and cities that never seem to sleep.

Ganga Arthi, a daily ritual, being celebrated at one of Varanasi’s Ghats. – Photo: smtt.com

Any silence you might experience here must come from within.

You can choose to be irritated by the constant noise or can choose to abandon yourself to a time-free state of mind. Try watching the ubiquitous cows as they meander gracefully through the tumultuous thoroughfares of old Varanasi and then – as the spirit moves them – casually enter the narrow, crooked streets that have been here for millennia, to forage through the food that has been generously provided for them in a thousand doorways. Or observe them as they sit tranquilly on their sacred haunches, oblivious to the ruckus of the traffic and the hawkers. They have what new age gurus might refer to as “an inner calm.”

Perhaps they are simply content to be what they are...sacred cows.

In Varanasi, the land of Lord Shiva, home to thousands of Hindu shrines, music and color seem inseparable from religious devotion. Orange-red flames from the crematoria on the banks of the Ganges lick the sky, day and night, while men dressed in white loincloths, with shaven heads, mourn the dead with their ardent chants, to ease the soul’s passage into the next world. Every morning you are awakened and every night you are lulled to sleep by the sound of drumming and chanting. The beating drums are a constant undertone to life in Varanasi, like liquid music running through your veins. At dawn and at dusk, 365 days a year, in the central Ghats (stairways) along the Ganges, monks in persimmon robes and their white-clad novitiates ring bells, chant Vedas, and swing pyramid lanterns.

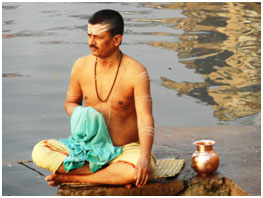

A Hindu devotee bathes in the Ganges. – Photo: RBS

Some nights, during the religious ceremonies, fireworks will pepper the sky with sparking gold, red and green patterns that then explode into millions of tiny lights, fireflies cascading down from the heavens, only to be swallowed up by the waiting Mother. Or you can track the orange moon waxing or waning and gaze at the shimmering orange, gold, and green reflections on the water made by the hotels, guesthouses, and shrines along the shoreline. The persistent boat vendors selling religious relics and trinkets will invariably bump up against your rowboat and thrust their wares under your nose. And prepare to be pursued in your rowboat by black sinewy columns of mosquitoes, swarming, circling, and then descending for the feed in syncopation with the drums. There is no escape. The bothersome mosquitoes must be accepted as an intimate part of the night’s rituals.

Not to worry. The Mother Ganges is always comfortingly nearby...along with the rituals and chants, the colorful shrines and temples, the burning corpses and stacks of wood piled to the sky, the wandering sadhus and turbaned seers willing to give you a face-reading for 500 rupees ($7.50 USD). Also ubiquitous are hundreds of flyers and posters for concerts; tabla, sitar and flute lessons; yoga and art classes; and even impromptu watercolor exhibits set up by young, hungry student artists on the steps of the Ghats. Education in the arts and religion are equally valued here – that is undoubtedly how Varanasi earned its moniker “the city of burning and learning.”

Japanese and Indian Musicians play at the Assi Ghat in Varanasi, known for its musical performances. – Photo: RBS

Take, for example, the Bhadri Kali guesthouse near the Dashaswamed Ghat, a lodging I chose on-line with my daughter, Leora, because we were attracted to the colorful flower mural in their entryway and the view of the Ganges from their rooftop. Music, we discovered, like the exuberant colors of the guesthouse walls in all of the rooms and in the corridors, is central to the lives of the two brothers, the Tripathis, both drummers, who run the guesthouse.

Vikas Tripathi lives most of the year in Spain with his wife and two children, where he manages six bands. But he comes back to Varanasi faithfully for several months each year to help his family manage the guesthouse.

His younger brother, Raavi, a virtuoso drummer frequently invited to perform with musical groups in Israel, is an expert on four kinds of percussion instruments. He likes to sit on the cajon, a wooden drum from Spain that looks like a crate, and play with both his hands and feet, alternating with the dunbeck (a drum which comes from Turkey and is popular in Israel), the tabla, (the drum native to India), and the djembe, an African drum.

Raavi is also the founder of a modest art school for poor children in Varanasi named Vagdevi. He launched the school eight years ago and now teaches some 40 students. He says he feels privileged to watch them grow in their musical and artistic abilities. At the same time, he still struggles financially to keep it alive. He counts on the money he earns from his paying gigs and through sporadic contributions by generous foreigners and locals. Sometimes a donation will appear in the form of a 25-pound bag of rice to feed the children lunch.

Flirting with the idea of becoming a non-profit or seeking the help of an established NGO to keep the school running, Raavi explains the complicated red tape inherent in the process. He smiles and nods his head conspiratorially, rubbing his thumb and fingers together in the international gesture for money. A daunting situation, he admits, but he is hopeful he’ll find a solution. Dreams are not easily abandoned in Varanasi. Just imagine how patient the Hindus of Varanasi have had to be for six centuries as they watched their temples destroyed by multiple invaders who hoped to convert them to Islam or Christianity. But the intruders never succeeded. The Hindus have rebuilt their temples and Varanasi continues to be the most dynamic center for Hindu worship in the world today.

Sacred cows enjoy their leisure in the narrow streets of Varanasi, where for thousands of years people have provided them food in a thousand doorways. – Photo: RBS

Vikas and Raavi and their sister, a talented henna artist, have tried many times in vain to convince their mother and father to sell another larger guest house they own near the Ganges and move instead to a more modern and spacious house in the newer part of the city, about an hour’s drive away. Their mother won’t budge. She can’t bear to part from the Ganges and what the Mother represents to Hindus.

The cows also seem to prefer old Varanasi. And who can blame them. They have an adoring cadre of local residents who will always make sure they have enough food and space to rest. In fact, one of the merchant shops in old Varanasi is famous for allowing a black bull to come daily and rest in the middle of the store during the hottest hours of the day.

Leora Sharone, Vikas Trapathi, and Ruth Sharone in front of the mural Leora painted for the Bhadri Kali Guest House.

Vikas is delighted when my daughter volunteers to paint a mural at their guesthouse to capture the relationship between Varanasi’s fiery sun, the funeral pyres, and the cool blue of the Ganges. Leora spends the entire last night of our stay on the landing leading up to the second floor with paintbrush in hand, the nearby sound of the Varanasi drums in her ears, beginning at dusk and when finishing at dawn.

Centuries pass. The cycle of souls continues as the crematoria send up their orange-red flames. Artists and religious pilgrims of all backgrounds – Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, Sikh, Christian, Jewish, and more – come from far and wide and return again and again to drink from the music, art, and spiritual wells that never run dry. Here in Varanasi, the oldest city on earth, time stands still while Mother Ganga sees all, embraces all, and forgives all.