Ancient African Traditions

A Pagan's Adventures in Egypt

by Don Frew

In 2005, I attended the annual meeting of the Global Council of the United Religions Initiative. That year, it was held at a retreat center near Seoul, South Korea. One day, we took a long bus ride to the Buddhist monastery of Haensa, during which I sat with Monica Willard, URI’s representative at the United Nations. A few hours into our journey, Monica mentioned that our next stop was supposed to be at a place called “Geoyang” and wondered if we were close. I said that the sign we just passed said “Geoyang,” so I assumed it was the next stop.

“You read Korean?” she asked, surprised. I said “Not when we arrived. But I learned the script in the last couple of days. Once someone explained that the glyphs were alphabetic characters, it was easy to figure out that the glyphs were mostly triliteral syllables – similar to Mayan script – but with an aesthetic component similar to ancient Egyptian.” When Monica stared at me, I realized what I had said and how it would sound to someone else. In my community, it’s common for folks of my generation or older to have at least a minimal acquaintance with at least one ancient or endangered language. In my case, it’s Latin and a smattering of Egyptian. It wasn’t until I entered the realm of interfaith that I realized how unusual this is, especially since many of my childhood friends studied Hebrew alongside English.

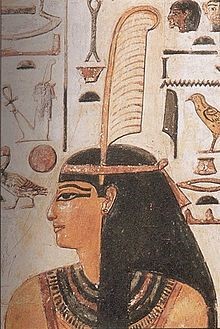

Maat wearing the feather of truth – Photo: Wikipedia

A fascination with the cultures of the past is deep-rooted in Neopaganism. A personal relationship with Gods and Goddesses inevitably leads to study of the religion, culture, and language(s) associated with them. While it is by no means necessary, there is a certain power to be found in addressing a deity in the language that was a part of its worship for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. It’s also true that very often religious concepts found in an ancient language don’t have clear counterparts in modern English. (The Ancient Egyptian word “Maat” is a good example. It is both a concept and a goddess. It is what is good, true, and real. It is the way of things. It is the underlying order of the universe, maintained through our own right action.) As we find profound spiritual inspiration in these faiths of the past, we also feel a profound sense of responsibility for their preservation and for the preservation of the material and immaterial cultures associated with them.

I am a Witch. By most accounts, Wicca has its roots in the fusion of Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, and Roman cultures in Britain. Even so, my heart has always belonged to Egypt. The first book I read on my own was a children’s book of Egyptian myths. I was hooked. In 1975, I had the privilege of taking a semester off high school to travel around the eastern Mediterranean with a friend and his father – an archaeologist on sabbatical. That was the first of five trips, so far, to Egypt.

In 2015, I traveled to Egypt to take a class in Ancient Egyptian recommended by KMT Magazine, the Scientific American of Egyptology – serious and academically sound, but for a popular audience. After several years of study on my own, the opportunity to learn more than the titles of professions and the names of kings, and then translate directly from the walls of temples and tombs, was fantastic! The ancient Egyptians spoke to me in their own words, through inscriptions they themselves had carved.

Hermes Trismegistus, floor mosaic in the Cathedral of Siena – Photo: Wikipedia

After the class, I took a side trip to Minya, a city in central Egypt, which would be the staging point for other trips. One was to Amarna, the site of Akhetaten, the city of Akhenaten, described in the October 2016 issue of The Interfaith Observer. Another was to Hermopolis, the sacred city that was the cult center of the God Thoth. Pronounced something like “Djehuty” by the ancient Egyptians, Thoth was the God of the Moon, of Writing, and of Magic. The Greeks identified him with their God Hermes (hence “Hermopolis”), and then the Romans with their God Mercury. Over time, Thoth became part of the composite God Hermes Trimegistus (or “thrice-great”). This God is one of my Gods, a central part of my spiritual life, and one of the tutelary deities of my coven – Coven Trismegiston. To visit the center of his worship in antiquity was like making a pilgrimage.

There was one snag… My guide and translator, Ahmed, while a very nice man, is a very conservative Muslim. I once tried to initiate a conversation about the relationship between late antique Paganism and early Islam, but that was shut down real fast. Ahmed made it very clear that he wasn’t the least bit interested in any Islamic sources on the subject. Instead, we had (rather dangerous) conversations about Egyptian politics.

Standing in front of a statue of Thoth – Photo: DF

At Hermopolis, modern El Ashmunein, I was dismayed to discover that the museum was closed. Not only that, but in the unrest around the Arab Spring in 2011, a number of archaeological sites had been looted, so the director of the Hermopolis Museum had ordered that everything that was not nailed down be moved into the museum and locked up tight. The museum had not been opened since then. All that was left to visit were the ruins of the Temple of Thoth (mostly covered by the ruins of a Christian basilica) and a statue of Thoth (depicted as a squatting baboon) that was too large to move.

I had brought with me a small cloth bag with items that the members of my coven had contributed to take to Hermopolis, to leave at an appropriate spot with an appropriate prayer, connecting all of the coven with this sacred place. It seemed that this statue was my best bet, or at least somewhere under the bushes of the surrounding garden. I looked around me. The museum guards were lounging by the gates, watching. After all, I was the only foreigner to visit in years and so a source of some entertainment. The same could be said of the village elders, women, and children on the other side. And there was the jeep full of guards ordered by the provincial governor to accompany me whenever I left the city. I was just a bit “on stage.”

I asked Ahmed if it would be okay to leave something under one of the bushes. “Like what?”, he said. “Well, I have the small bag. It’s organic. It will break down.” Why would you want to do that?”, he asked. “Well,” I said, “Thoth is kind of important to me and my people and I have a small something I’d like to leave near the statue.” Ahmed looked atl me, then at the bag, then back at me. “I’m going to go over there,” he said, pointing away from the statue. “What you do is your business.” He wasn’t going to stop me, but he wasn’t going to help or be involved in any way. Things went off without a hitch, although I still wish I could have left my offering at the feet of the statue.

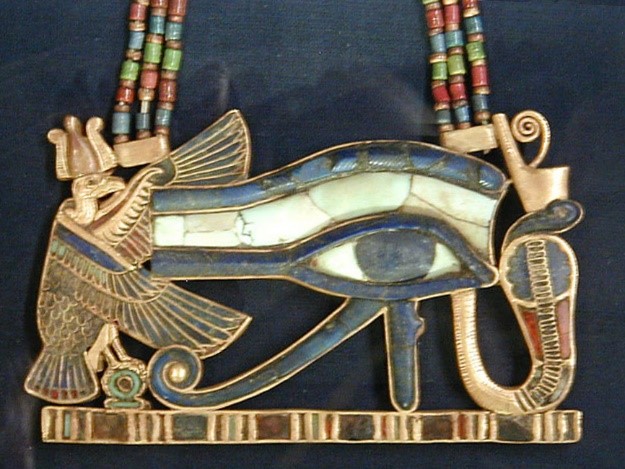

Amulet in the shape of the Eye of Horus, a common magical symbol – Photo: Wikipedia

Things went differently when I returned to Egypt in 2016. This time, I was traveling with a friend named Matt. Matt is a Kemetic, meaning his own spiritual practice is part of an ongoing reconstruction of the religion of the Ancient Egyptians. In his case, it has gone far beyond learning a “minimal” amount of ancient Egyptian. He is as fluent as any Egyptologist I’ve met and is part of a network of scholars working on re-creating the actual sound of spoken ancient Egyptian (based in part on its relationship with other languages of the Afro-Asiatic language group, on the Coptic that descends from it, and the way that other Bronze Age languages tried to spell out foreign Egyptian words). When he reads a hymn in something closer to what it actually sounded like, you can feel the power in the speech. Many times, he would be reading something off the wall of a temple and others tourists nearby (what few there are nowadays) would cluster to listen. Matt’s fluency in Arabic helped with making local connections, too.

Matt brought small images of his favored deities on something the size of prayer cards. With these, he performed morning ceremony every day and, since they were small enough to carry with him, whenever the opportunity presented itself in the many temples we visited. Shortly before we left San Francisco for Egypt, Richard (the founder of Matt’s Kemetic group and a good friend) had died. Richard had always planned to visit the Great Temple of Amun at Karnak and perform ceremony there. Matt brought a flower from Richard’s grave with him and hoped to perform ceremony at the temple on Richard’s behalf. We arranged to enter the Temple of Amun before sunrise one day and have the sanctuary to ourselves. Our guide on this trip was Mohamed. We worried about how to explain this to him and if he would interfere.

The afternoon before our sunrise visit, Matt broached the subject with Mohamed. Mohamed surprised him by saying “Ah, you wish to perform a tawṣiya wagiba.” Matt spoke with him in Arabic about this and later explained to me that this means an “obligatory request.” It is a tradition of carrying out a task that someone had asked you to do before they passed away. Mohamed understood and wished to help. When we reached the sanctuary, he went and made sure that the guards would not interrupt us. Moreover, he stood by respectfully, with me, while Matt performed the Morning Hymn as sun rose behind the temple and the sun shone down the center-line to where we stood.

The moment was moving and magical, and couldn’t have happened without the respectful help of our Muslim friend.

Entry to the Temple of Ptah – Photo: DF

On that same visit, we went to explore the less-often visited parts of the temple-complex of Amun. To the north is a small Temple of Ptah, consisting of several successive gates leading to a small chapel, with statues of the God Ptah and the lion-headed Goddess Sekhmet.

As we approached the chapels, we saw another person, guide or guard, we weren’t sure – standing inside. There was a statue of Ptah, missing its head, in the central hall and a locked door on the right. We asked about seeing the statue of Sekhmet. The person unlocked the door, went into the completely lightless room, and shooed out a local woman. He explained that women would come there to pray in that chapel, asking Sekhmet to send them a baby! This was a bit of a surprise, and we felt bad for being responsible for cutting short her prayers. At the same time, we were pleased to find that in Egypt the old Gods are still alive – not just in the vibrant wall paintings and in the spirituality of Pagan visitors from the West, but in the hearts of the local people as well.

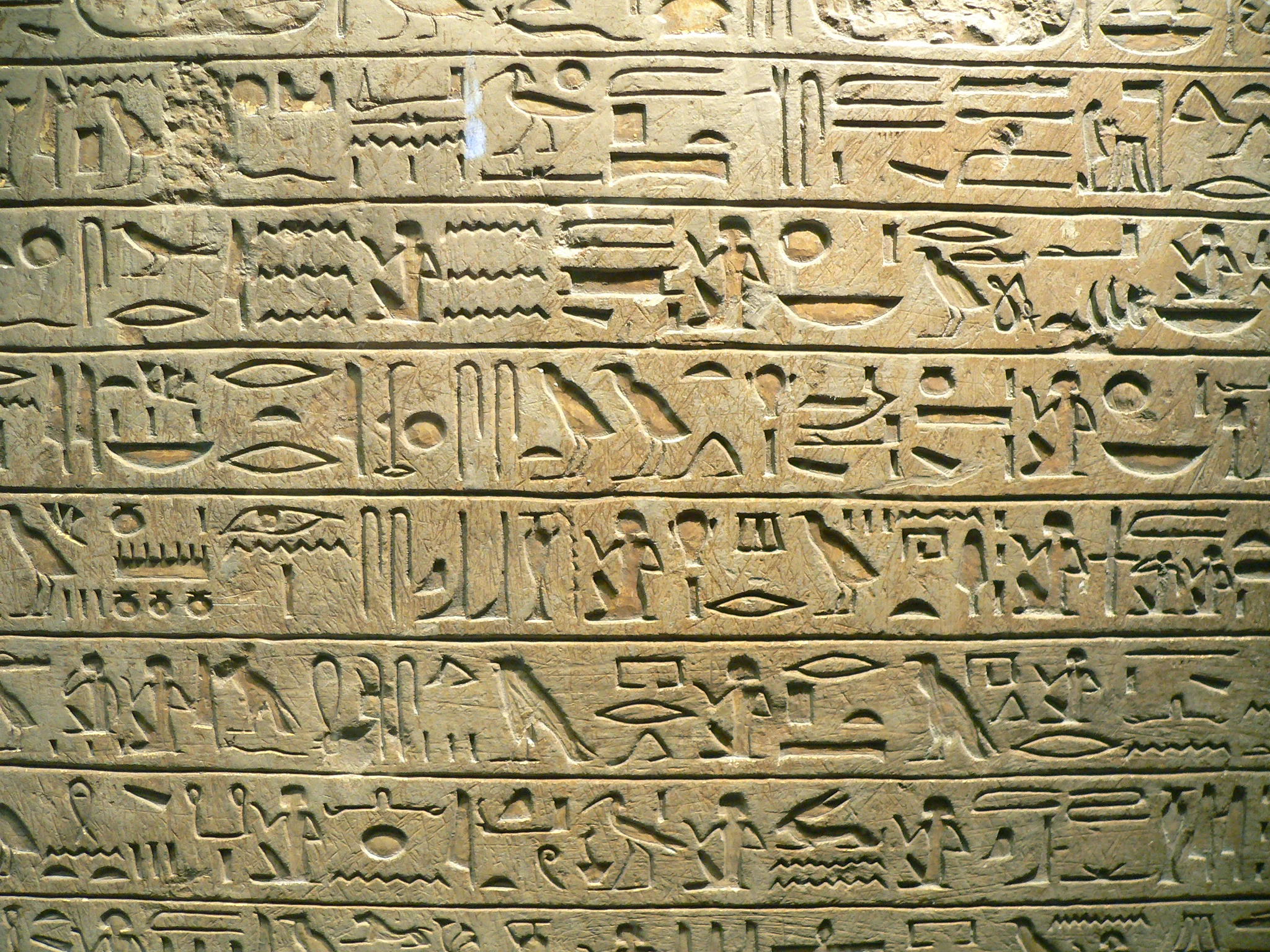

Header Photo: Stele of Minnakht, chief of the scribes. during the reign of Ay (c. 1321 BC) – Photo: Wikimedia