When Women Lead

Finding Power in Ribbons

A TIO Report

The United Nations is perhaps the most diverse ‘community’ in the world, and yet in its early years it was adverse to anything ‘religious.’ Wasn’t their territory – until Robert Muller (1923-2010), Assistant Secretary-General of the UN for 40 years, slowly brought his interfaith-friendly influence to bear in this family. He is credited with helping the United Nations and its global representatives grow past their religious phobia. But Muller could never have achieved this without the leadership and brilliant collaborative work of a series of women including Avon Madison, Joan Kirby, Alison Van Dyk, Deborah Moldow, Monica Willard, Grove Harris, and a host of others from the women’s movement and the interfaith movement. All have been women particularly committed to working together for global peace. They and their organizations have networked with dozens of other UN Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), raised critical issues on behalf of women and children, and inspired interfaith harmony and peacemaking celebrations in countries all over the world. Books will be written telling their stories.

Justine Merritt – Photo: justinemerritt.net

One of the most powerful projects generated by this cohort of interfaith women started modestly, when a 61-year-old woman took a trip to Japan in 1975. She began a journey that millions of peace lovers around the world joined. The Ribbon project was born on August 5, 1985, and in 1991 The Ribbon International became a UN NGO.

In this day of week-long media cycles and headlines all day long, extraordinary events and projects come and go. In the rush, so much is forgotten. Very few under retirement age, probably, know the name Justine Merritt (1924-2009). This report, which had to lean into an excellent article in Wikipedia for details, points to the remarkable achievement of one person and the global interfaith action she inspired. Her story is a critical part of any peace lover’s heritage and needs to be owned by us. It is filled with lessons about making a difference collaboratively, which currently seems to be the task at hand.

** ** **

Thirty years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Justine Merritt visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and was moved in ways which changed her life. Back home in Denver, Colorado in the years that followed, reflecting on the specter of human annihilation, she bumped into the following issue: “What I cannot bear to think of as lost forever in a nuclear war.” Then an idea surfaced. She could record on a ribbon what she herself couldn’t bear thinking about losing; and then could tie her ribbon to some else’s, so that eventually they would get hundreds, then thousands, of ribbons tied together in a pro-active gesture of peace and care for the Earth. In 1982 she tried out the idea on her Christmas-card list. Friends told friends and family about it. Merritt started getting calls and invitations, more than she could handle by herself. She turned to her friend Mary Frances Jaster to help her with scheduling, and everything grew from there.

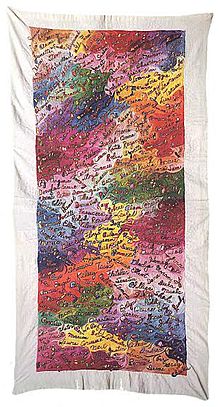

Justine Merritt's first Ribbon Panel is embroidered with the names of people she loved. Photo: Wikimedia, Michelemariesimone, Cc.3.0

They decided to invite people everywhere to contribute 36” x 18” cloth panels responding to the issue. These panels would be gathered and tied together in Washington DC on August 4, 1985, on the 40th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing.

The power of a good idea, conveyed personally – What couldn’t I bear to lose? – and the fears at the time over the Cold War, gave the campaign a deep, personal dimension. It grew by leaps and bounds. Church Women United organized a campaign across the U.S. Every state sent panels, with California by itself sending more than 3,000. Panels came from Russia, England, Germany, New Zealand, Italy, Canada, Australia, the Netherlands, and Puerto Rico.

The theme transcended the typical conservative-liberal, right-left divides. Millions heard about the ribbons in their religious newsletters. And the project enjoyed coverage from McCalls, People, Vogue, Time, the Washington Post, and Mother Jones. The project was not ‘owned’ by any particular organization, making it a something for all people. Along with Church Women United, major collaborators included Peace Links, led by Betty Bumpers, and the Center for a New Creation, which organized the event in Washington, D.C.

On August 3, 1985, the night before the ribbon tying, 5,000 attended an interfaith service at the National Cathedral to celebrate the project, reportedly the second-largest event ever held there. Hiroshima and Nagasaki survivors attended and spoke. Worship included dancing, meditation, and music, highlighted by the Howard University Gospel Choir.

The next day 27,000 panels stretching 18 miles were tied together and, essentially, wrapped the city and more. They circled the Pentagon, went down to the Potomac River and into the city, past the Lincoln Memorial, along the Mall, and around the Capital Building, and then back all the way to the Pentagon. Thousands lined the poignant 18-mile gesture of peace. Academy-Award winning documentarian Nigel Nobel made a 45-minute film of the August 3-4 events. Embedded above, it is beautifully produced, a particularly good resource for anyone interested in studying the collaborative genius interfaith women can bring to bear in a world that needs better solutions to peacemaking.

In 1993, United Religions Initiative UN representative Monica Willard joined Justine in taking the project to the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, where it was embraced. Ribbon projects continue at sites around the world every year, particularly on International Day of Peace (September 20), International Women’s Day (March 8), and Earth Day (April 24). You can visit annual ribbon events in Lugansk, Ukraine or in Gas City, Indiana; in the Gaza Strip or New Zealand; in Hiroshima and other communities around the world. A national project has gone global.

In a world with as much disagreement and violence as we suffer today, one wonders how much influence a ribbons project makes. Or to turn the question upside down, would the world be worse if we did not have leaders who championed peace amongst us? That’s a fairly easy ‘yes.’ And whatever one’s answer, the peace activists among us will continue the quest with the same courage Justine Merritt exemplified.

Monica Willard, United Religions Initiative Representative to the United Nations, contributed to this report.