Living in Sacramental Space

Katy Perry's Not the Only One Who Wants to Live in a Convent

by Megan Sweas

I moved into a convent 10 years ago this summer.

My roommates were not Catholic sisters, but other recent college graduates, who sometimes acted a little too much as if we were still living in a college dorm. But most of our time was dedicated to service of our community – teaching, leading afterschool programs, counseling pregnant teens and gang members, working with the elderly – just as the sisters who preceded us in the convent had once done.

Amate House, once a convent, now a Catholic volunteer program – Photo: Zocolo Public Square

The news that pop star Katy Perry wants to buy a former convent in Los Feliz, California has me thinking about my days at Amate House, a full-time Catholic volunteer program in Chicago. The Los Angeles Times broke the story that two nuns are blocking the archdiocese from selling the estate to Perry, who wants to live there. Early coverage of the story centered on the sister’s disapproval of the “I Kissed A Girl” singer.

My fond memories of convent living, though, make me wonder if the question of whether Perry is a suitable successor to the sisters misses the point. As our society become less connected to religious institutions, it may be more important than ever for communities to think creatively and sensitively about how to make use of formerly religious spaces.

I had never imagined that I would live in a convent. Amate House operates three houses, two of which were convents, with both male and female volunteers, and it is part of the Chicago archdiocese. But I approached it more like Peace Corps or Teach for America: an opportunity to do something special, learn about life in the inner city, and give back – not to live out my faith. I identified myself as a “practicing-but-not-believing Catholic.” I had volunteered with my high school youth group through college, but I was more interested in Buddhism than Christianity.

Though I defied typical categories – neither fully Catholic nor a religious “none” – my experience reflects the trend of young Americans disaffiliating from institutional religion and forming their own religious identities and understandings.

My grandmother, in contrast, grew up wanting to be a Catholic sister. Unfortunately for her (but thankfully for me), she lacked the education to join a religious congregation. Instead, she got married and raised my father and his four brothers.

Seeking to understand my recently deceased grandmother’s devotion – why would a woman voluntarily commit her life to a patriarchal church? – I wrote about Catholic sisters for a class in college. The nun in her nineties that I profiled couldn’t explain her vocation other than as a call from God.

Her order had once occupied a huge motherhouse in my hometown and sent teachers to schools throughout the Midwest. In northwest Iowa, she had taught art to a budding cartoonist who would go on to work for Disney and draw the genie in Aladdin. But by the time I visited, they had moved to a smaller house, essentially a nursing home for sisters.

Their grand old motherhouse became Loyola University Chicago’s education school. The sisters were happy that a Catholic institution was continuing their legacy, but then Loyola moved to sell the property to a developer that planned to raze the convent and put in single-family homes.

The city intervened, and the building still stands as senior housing. But the sale of convents and churches to developers is not unusual. Around the same time, my parents moved into a development in a neighboring suburb that had been built on the grounds of a former convent. And when I lived in a convent, my window looked out on a Protestant church that had been converted to condos.

Such examples will become more common as people move away from institutional religion. Places that once brought together a community become individual units, our architecture seeming to reflect our spiritual trends.

Yet, many still long for a sense of togetherness, even if in untraditional ways. My convent roommates and I were not all regular churchgoers, despite living above a chapel where daily mass was held. Our “church” came in the form of meals, reflection nights, and service to the broader community.

But buildings can’t be preserved just for community. In exchange for our service, our work sites paid Amate House small fees to cover our living expenses, including our convent housing. Another solution is to make churches into community arts centers, renting space out to nonprofits during the week. Both situations provide a win-win for religious institutions and nonprofit organizations.

Pope Francis visiting refugees in Centro Astalli in Rome – Photo: Jesuit Refugee Service

A year or so ago, I met with two sisters in Chicago who were in the process of opening a migrant shelter in an old convent, supported by an interfaith organization. They told me what Pope Francis had recently said at Centro Astalli, a refugee center in Rome: “Empty convents are not for the church to transform into hotels and make money from them. Empty convents are not ours, they are for the flesh of Christ: refugees.”

Intrigued by this tension between money and mission, I applied for and received an International Reporting Project fellowship to find out if Pope Francis had affected Italy’s welcome of migrants. Visiting Centro Astalli and other refugee centers around Rome, I met many migrants living on the street or in abandoned buildings, unable to find work or housing in their new country. Two men showed me how they survived while homeless in Rome, sleeping at Termini train station, passing their days in a park behind the Coliseum and seeking services at churches and convents.

For my last few days in Rome, I checked into a convent hotel along their daily path, a few blocks from Termini. Once again, I found myself in a spartan single.

My convent hotel was clean and comfortable, European beds being what they are. And for not much more than the price of a hostel, I had a private, quiet space.

Four sisters lived on the top floor, and one of them told me that they make themselves available to travelers for either logistical or spiritual concerns. Many orders consider hospitality to pilgrims as part of their mission. In addition to tourists, they host student groups and families of patients from a nearby hospital. And the hotel helps fund their work in the missions.

Yet, when I saw the generous breakfast spread for what seemed like a handful of guests, I couldn’t help but think of the homeless migrants I had met on the streets of Rome. If the government, churches, or nonprofits paid for even a few migrants’ room at this convent, I wondered, how would the tourists staying there react?

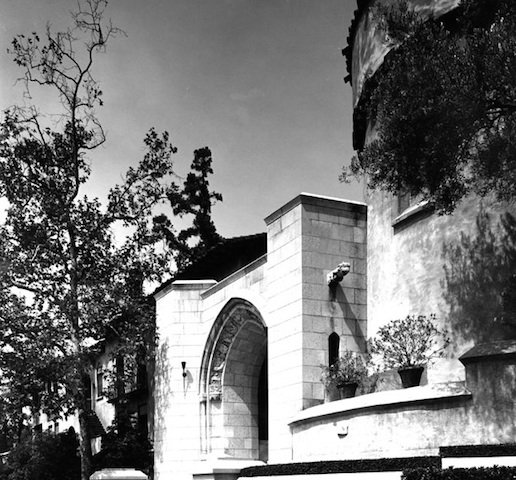

Entrance to Los Feliz Convent, taken in 1927 – Photo: Jim Lewis, Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection

Some argue that the pope’s statement against convent hotels reflects the male hierarchy’s desire to control the hard-earned assets of women in religious orders. In Los Angeles, the Katy Perry story is more about who manages the proceeds of the sale – the nuns or the archbishop – than whether Perry or someone else is the next owner of the convent.

I, for one, would trust a group of sisters more than the archdiocese to put the millions earned from the sale to good use. Yet the sisters’ buyer, a driver of gentrification who is also currently refurbishing the former Pilgrim Church into a hotel and restaurant, is no more likely than Perry to transform the convent into a homeless shelter.

As religious institutions decline, not all religious buildings will survive. But as someone who enjoyed living in a convent – temporarily – I would hope that some could be transformed into shelters, art centers, homes for nonprofit or volunteer organizations or other projects that benefit the whole community.

With a little creativity, Catholic sisters’ spirit can live on in a very concrete way.

This article was originally published by Zocalo Public Square, July 23, 2015. Following years of litigation, Los Feliz Convent was sold to Katy Perry this past March.