Challenging Intolerance with Spiritual Art

Epiphany at the Alter of a Sand Mandala

by Billy Doidge Kilgore

Five Buddhist monks stand in a row, torsos wrapped in maroon robes and scalps adorned with golden headdresses. In their arms, they hold cymbals, drums, and horns. Facing an altar draped with bright cloth, they curl their lips into an “o” shape, jaws shifting, as they create a low, guttural, vibrating sound that rattles through the art gallery.

As I listen to the gruff chanting, my distracted mind is brought into focus. I came to the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, my hometown, to watch Tibetan monks construct a Mandala Sand Panting – an intricate, temporary creation made from colored sand. I came to witness the spectacle, but as I stand, shoulder to shoulder in the gallery with other spectators, I sense within me a desire for more than a show.

Just when I feel tranquil, the monks ready their instruments. Bells ring. Cymbals clang. Drums beat. Horns shriek. A jarring, disordered sound fills the room – a wake-up call – preparing the space for the mandala.

Photo: INTER

The monks strip cloth from the altar, clearing the flat, square surface. In its place they stretch chalk lines, rotate protractors, and mark with white pencils; their careful work generates an intricate grid, resembling the map of an urban area. Hundreds, maybe thousands of lines intersect. Inside the grid, the outline of the mandala forms, a large circle containing complex geometric designs.

Creating a mandala from sand is a spiritual practice, an act of meditation and devotion. Tibetan Buddhists believe the mandala is inhabited by deities, serving as guides for individuals on the path to enlightenment. These monks from the Drepung Loseling Monastery tour the United States constructing mandalas in art galleries, college campuses, and theaters. The ancient art, blessed by His Holiness the Dalai Lama, injects a unique spiritual practice into public spaces, allowing passersby to experience the beauty of Buddhism. “The first goal,” says Geshe Nyima Tsering, their spokesperson, “is to make a little bit of contribution to world peace and purification.”

My knowledge of Buddhism is limited to what I’ve read in textbooks, learned from lectures, and gleaned from brief meditation classes. But I am spiritually curious. An ordained minister, I visit all of the prayer labyrinths in my city. I delight in the silence and chanting of Taize worship. So I was thrilled when the local museum announced they are hosting Tibetan monks.

Photo: INTER

I peer over shoulders and heads, observing the monks as they grip chak-purs, narrow metal funnels containing colored sand. Each holds the chak-pur at a forty-five-degree angle and rubs a metal rod against it to jar sand loose. Flicking their wrists, moving the rod up and down, the monks work with the precision of a medical team performing surgery. Starting in the center, they pour red sand into a lotus bloom representing Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

Two days later, I return with my three-year old son to see the monks’ progress, now far along in their work. I lift him from the stroller and hold him as we observe the monks bent over the altar, gripping their chak-purs. They pour in silence, walking to a side table to refill, scooping sand from a bright palette of silver bowls.

Photo: INTER

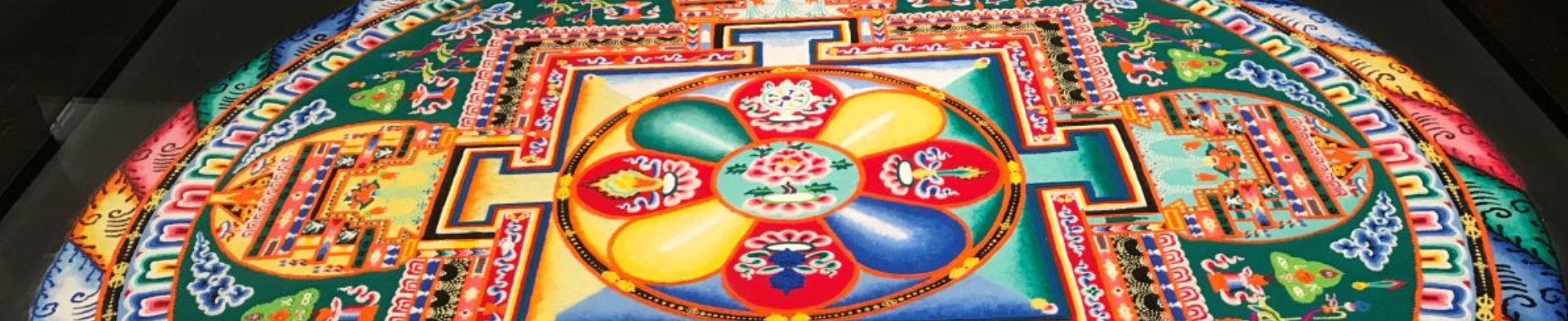

The mandala, a fusion of colored sand – red, green, yellow, blue, and white – seizes my sight. A celestial palace surrounds a multi-colored lotus petal with four walls, containing layers of intricate patterns and ornate gates. Outside the palace walls, an expansive green garden is filled with jewels, flaming swords, precious umbrellas, and a wish granting tree.

I glance at my son’s face, his toddler eyes spellbound, watching the men with shaved heads wield their tools. Turning my attention back to the altar, I study the monks’ rhythmic movements. My thoughts calm; and my mind focusing on the ritual unfolding. All the thoughts I’d been juggling – lunch plans, unfinished errands, misplaced parking tickets – drop to the ground as if I only have one task: to be present for this holy work. The monk’s quiet focus brings me back to the part of my own spirituality I value most: the rich exploration of the inner life.

The next morning, I sit on the couch with my morning coffee, thinking of the monks and the serenity of the gallery while my three-year-old son hurls Legos and screams, I struggle to think of an example of a spiritual practice from my own tradition, Christianity, that is brought into a public space in a similar way.

Then I remember Ash Wednesday. In recent years, clergy have left church walls to perform the ritual that denotes the first day of Lent, marking foreheads in coffee shops, subway stations, and busy intersections. The sign of the cross (worn for the entire day) reminds participants of their mortality and reliance on God. A beautiful ritual, but not as demanding as constructing a mandala.

Sipping my steaming coffee, it occurs to me that we need the spiritual practices of unfamiliar religions as much as our own because their fresh perspective offers an opportunity to move beyond ourselves. The distinctive devotion of the monks lured me away from my self-absorbed thoughts. I don’t know I need a wake-up call until I stumble into a moment that opens my eyes to a reality larger than myself. We need novel spiritual practices to expand our consciousness when it narrows, to pull us beyond ourselves, especially when we fall into a rut with our own practices.

The next week I return with my son to see the finished mandala. The monks have left the visual arts center, the Dalai Lama’s picture is gone, and the table displaying the colorful sand bowls has been removed. All that is left is the altar in the center of the gallery, covered in glass, containing the mandala.

Photo: INTER

During my final look at the mandala, an epiphany resounds through my entire being: we must make the effort to bring our religious traditions and rituals into public spaces where others can absorb their power and engage the spiritual dimension that is an essential part of our humanity. If we keep them behind the walls of our sacred spaces we deny others the opportunity to gain appreciative knowledge, the knowledge we need to build a sturdy foundation to support our complex religious landscape.

Where do we start? We can mine our different religious traditions for rituals that not only exhibit beauty but offer an opportunity for the uninitiated to transcend their self. We can share spiritual practices that disrupt routine and create space for others to examine inner life. We can choose the practices that call on participants to use their senses to experience the best of our faiths.

By bringing spiritual practices into public spaces, we can challenge ignorance and intolerance and, hopefully, minimize the suffering caused by misunderstanding. As a Christian, I imagine taking Holy Communion – the bread and cup – into unlikely places to induce the intersection of the divine and busy modern life. The thought of offering a place at God’s table in a train station or crowded park causes my insides to vibrate.

I hope to go back to the arts center in May when the monks return. They will sweep the sand into an urn, proceed out the front door of the museum, turn right on Broadway and carry it to the nearby river. The sand will be poured into the water to diffuse and spread its positive energy, moving from tributary to tributary until it reaches the ocean, sharing peace and purification with the world.

This article was originally published by INTER, a publication of the Interfaith Youth Core.

Header Photo: INTER