The First Modern Guru

Review: The Life of Yogananda by Philip Goldberg

by Paul Chaffee

The religions of India – Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Sikhism – are less familiar and stranger to most Americans than the Abrahamic religions, which have dominated America since Columbus. Until Ralph Waldo Emerson and his friends discovered India’s sacred texts, the spiritual motherload of South Asia was virtually unknown in the West. And to this day Christian-Jewish-Muslim issues dominate the interfaith movement in Europe and the Americas.

So it is counterintuitive, indeed startling, to discover how deeply Hinduism’s wisdom has entered the spiritual DNA of America. For fundamentalists from any tradition, this may be deeply distressing. For anyone else, whether spiritually inclined or not, the new perspective may be illuminating, even transforming.

Nearly eight years ago Philip Goldberg’s American Veda made the case for how much America has absorbed from India; the subtitle of that book is From Emerson and the Beatles to Yoga and Meditation – How Indian Spirituality Changed the West. It details important Dharmic elements in the religious zeitgeist of the times, without which anyone’s vision of religion in the U.S. will be distorted.

Teachers from India

Two teachers were particularly central in this East-West spiritual development. The most famous in interfaith circles is Swami Vivekananda, who electrified the audience at the 1893 World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, sparking what is known as the modern interfaith movement. Afterwards he traveled widely, taught, and founded the Vedanta Society. In 1902, nine years after that first Parliament, at age 39, Vivekananda died from a burst blood-vessel in his brain while meditating.

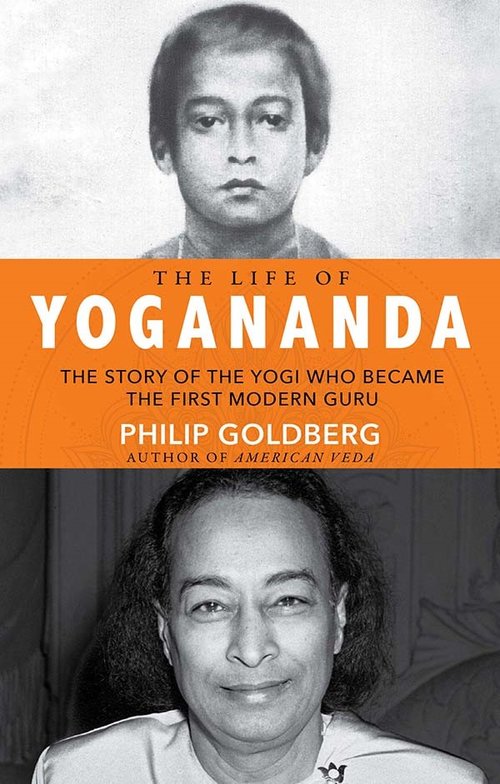

A little less known in the interfaith movement, but more influential in the long-run, is the teacher who became known as Paramahansa Yogananda. He came to the United States in 1920 at the age of 27. Now Philip Goldberg is back with The Life of Yogananda – The Story of the Yogi Who Became the First Modern Guru. This guru received considerable attention in American Veda, but Goldberg dives much deeper this time, reviewing a library of literature and previously untapped documents, as well as interviewing two people who know about the man who grew up named Mukunda Lal Ghosh. Goldberg takes us day by day, week to month to year, through the details in the life of a saint, as many feel, whose work has transformed millions of lives.

We meet Mukunda as a child with a voracious spiritual appetite, preferring hours of meditation or ceremony to studying his school books. That vital spiritual engagement lasted throughout his life, a bit more than half of it spent teaching, writing, and creating community in the U.S., where eventually he became a citizen.

Goldberg’s best research suggests that Yogananda was a chaste man, a vegetarian, and teetotaler. At the same time he loved to cook for people, play a variety of Indian instruments and lead singing worship sessions, organize practical jokes, visit museums, and watch movies. Always on the go, he was a passionate sight-seer. A master orator and skilled teacher, circumstances forced him to also become a businessman, fundraiser, and manager of employees and volunteers.

In the middle of this continual activity, Yogananda’s teaching and writing dominated everything else, keeping him centered and focused.

In all he was an interfaith wise man grounded in Hindu assumptions:

… it can safely be said that he presented the basic premises of Hindu philosophy: that our true identity is One with the omnipresent Spirit that permeates and transcends Creation; that fulfillment derives from awakening to that reality through direct experience; that contact with the Divine can be cultivated through systematic, predictable – and therefore scientific – yogic methods; that the universal, nonsectarian practices he teaches are both spiritually enriching and a boon to a better material life. (p. 126)

Photo: pxhere

Of course, Hinduism is at least as variegated and complex as, say, Christianity. Yogananda’s particular tradition was Kriya Yoga, which he defined as “a yogic technique, taught by Lahiri Mahasaya, whereby the sensory tumult is stilled, permitting man to achieve an ever-increasing identity with cosmic consciousness.” Where Christians emphasize “salvation,” bestowed by God out there, Yogananda’s aim was “self-realization,” recognizing God within us. Self-realization, he wrote, is “the knowing — in body, mind, and soul — that we are one with the omnipresence of God; that we do not have to pray that it come to us, that we are not merely near it at all times, but that God’s omnipresence is our omnipresence; that we are just as much a part of Him now as we ever will be. All we have to do is improve our knowing.”

An Interfaith Guru

Within this Hindu framework, Yogananda’s point of view is always an interfaith perspective. Regardless of a religion’s theology and history, all traditions attend to the spiritual life of their followers. This ubiquitous element within religion is the starting point for Yogananda. In 1942 he created the Self-Realization Church of All Religions. At its opening he said “I dedicate this church of all religions … unto all the soul temples of Christians, Moslems, Buddhists, Hebrews, and Hindus, wherein the Cosmic Heart is throbbing equally always…” (p. 260). A consistent theme in his work is a Vedic understanding of Jesus; two of his books were devoted to the subject, The Second Coming of Christ: The Resurrection of the Christ Within You (first published in 2004) and The Yoga of Jesus: Understanding the Hidden Teachings of the Gospels (first published in 2007).

There was an incredible thirst for Yogananda’s message in the early 1920s in America. The young teacher spent months in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and then on to cities across the country, finally finding his home in southern California. Tens of thousands attended his free lectures, which were followed up by 12-part courses which cost $25, income which funded the guru and his growing young movement.

Delegates of the 1920 International Congress of Religious Liberals at Boston (Yogananda center) – Photo: Wikimedia

While it’s clear how much Philip Goldberg cares about his subject, this book is no hagiography. He doesn’t hold back in delivering the full story. Suddenly becoming a religious guru and a celebrity, having the attention and income (or lack thereof) that come with it, while relating to hundreds, then thousands of people, means your path will be shot with potholes. Along the way circumstances forced Guru Yogananda to serve as a financial manager and community leader as well as teacher. We read about the lawsuits, occasional devotee relationships turning sour, about some who were jealous of his success, about the impact of the racism and religious bigotry of the era. Over and over Goldberg tells the whole story, letting readers make their own judgments.

For instance, what do you do in this day and age with a life and set of teachings as rife with ‘miracle’ stories as the New Testament? Our author tells us the stories, where they come from, and how they are variously understood – then we’re left to our own conclusions. A sense of fairness prevails, and the dozens of controversies that might crop up along the way never become arguments. Goldberg’s prose is a marvel, going down as easily as ice cream on a hot day. He offers color and context, slipping in details that provoke an ‘Aha!’

For example, how do you characterize New York City in 1923 when our young teacher visited and began lecturing? Here is a snippet:

When Yogananda settled in for his extended stay at the Hotel Pennsylvania, the roar of the ‘20s was not yet full throttle but was growing louder by the day. New York City was the center of that manic universe, a frenzy of stock market fever and materialist fantasies; speedy autos, racing pedestrians, and zooming subways; hot jazz, Charleston dancing, and bootleg booze – an oddly perfect place for an envoy of inner peace who said, “Where motion ceases, God begins.” (p.121)

His first New York lecture was at a packed Town Hall, remarkable considering the number of spiritual teachers from India who had already visited New York. Among these was Rabindranath Tagore, a Nobel Laureat who had done a lecture tour in New York. (p. 123)

Except for a one-year return to India in 1935-36, Yogananda spent the rest of his life in the U.S., mostly in southern California, though he did not cease traveling and lecturing until the final years of his life. When Paramahansa Yogananda died in 1952, he left a considerable legacy. Today there are 800 self-realization fellowship groups, centers, temples, and retreat facilities around the world.

In his final years most of his time went to writing, including his masterpiece, Autobiography of a Yogi (1946), a 500-page book that has sold more than four million copies and been translated into nearly 50 languages. Goldberg is often asked why he would write a biography when Yogananda’s own memoir exists. He points out that only ten percent of the autobiography is devoted to Yogananda’s years in the U.S., where he spent most of his adult life; and that there are big gaps, where years at a time are summarized in a sentence or two.

Altar of the meditation circle Langerringen near Augsburg in Bavaria, Germany. From l: Mahavatar Babaji, Jesus, Bhagavan Krishna, Paramahansa Yogananda – Photo: Wikimedia

For whatever reason, having these two books side-by-side provides a long-overdue chapter in the history of religion in America. We all are a part of this story, though that may come as a surprise. Consider these common-places, for instance: All paths lead to God … God is within you … become the best you that you can be. Though most don’t realize it, these notions derive more directly from Dharmic traditions than Abrahamic traditions.

As you turn the pages, you begin to see a larger context where a web of wise Indian men and women with various holy titles represent an unofficial but interconnected spiritual family where faith and practice are lived out and passed from one generation to another. The family you are born into and your spiritual family, both are critical in India. So it is appropriate that Yogananda’s close relationships with his father, a high-level railroad man, and with his guru, Sri Yukteswar, who called and commissioned him to take India’s wisdom to the West, are among the most compelling story-threads in the book.

An important added benefit in reading this splendid biography deserves mention. The book is an extended case study of the guru-devotee relationship, a complex relationship not easily understood in the West. This includes learning how Mukunda received the name Yogananda, and much later in life, why he was given the honorific Paramahansa.

Header Photo: pxhere