TIO Public Square

The Contemporary Public Square

by Robert P. Sellers

While the term “public square” may be vaguely familiar to most of us, it is appropriate to provide an explanation of the history and varied uses of the space to which this concept refers. The public square is an open, public place in many cities or even villages where people gather, typically located where two or more streets meet. Synonyms such as town square, plaza, piazza, civic center, urban square, market square, or the heart of the city suggest the many ways this space has functioned around the world.

Photo: Wikimedia

According to the Sandra Day O’Connor Institute for American Democracy, the public square dates back to ancient Greece and Rome, where it served as a place where “citizens could come together to discuss politics, exchange ideas, and engage in commerce.” In colonial America, these squares could be found “near essential buildings like town halls, courthouses or churches” and were “used for political rallies, town meetings, and military drills.” The Institute explains the value and meaning of community spaces:

Public squares are symbols of freedom and democracy, and people use them as places to voice their opinions and influence the political process. Leaders would and do often give speeches and debates in public squares to talk about important political issues. Public squares also provide a platform for public discourse and debate, allowing citizens to exchange ideas, listen to the views of others, and engage in respectful dialogue. This helps to promote an informed and engaged citizenry, which is essential for the functioning of a democratic society.

But public squares have not always been places where civil, respectful and peaceful exchanges have been made. In truth, public squares also have a bloody history.

Crucifixion as a public spectacle likely originated in Assyria and Babylonia, but was later adopted by the Persians in the 6th century BCE, then was passed down to the Greeks and the Romans, who perfected the agonizing form of capital punishment for anyone perceived to be a threat to the Empire – the most famous example being the crucifixion of Jesus on the municipal mount outside Jerusalem known as “the place of the skull.” The torture and execution method known as “death by a thousand cuts” was instigated by imperial China beginning in the 10th century, introduced to a Western audience in the Steve McQueen movie, The Sand Pebbles, in 1966.

Beheadings of the wives of kings, like Anne Boleyn, or the drawing and quartering of traitors, like the Scottish warrior William Wallace, were conducted at the Tower of London in 13th-century England. Death by the guillotine in France – somewhat more humane than manual beheadings or other cruel forms of execution – was first practiced in France in 1792 when Nicolas-Jacques Pelletier, a robber and murderer, was executed in front of the Place de l‘Hôtel de Ville in Paris. These methods of punitive death were carried out in public spaces as a warning to the populace. In the American colonies, law-breakers were often placed in wooden stocks for communal disgrace and abuse, and in the Wild West, cattle rustlers and bank robbers were often hanged in the town square, before mesmerized and rowdy crowds.

The temple of Hephaestus, as seen from the archaeological site of Ancient Agora, Athens, Greece — Photo: Wikimedia

Oxford-trained philosopher, economist, and writer Jonathan Glancey describes the agora, or central meeting place at the heart of the Greek city-state, which was not only famous but sometimes infamous. He notes that all over the world, every public square since the Greek Empire has reflected elements of the ancient agora. Accordingly, public squares were “where tradespeople and philosophers, poets and politicians rubbed shoulders and where, too, the public complained and demonstrated and, at times, were met, dispersed and even slaughtered by forces of the regimes they tried to take to task.”

So, as Glancey suggests, the agora was not only a place of carousels and puppet shows, but sometimes of protests and even revolution. Violence has marked some of the public squares throughout history, which has created the term “agoraphobia,” or the fear of public places. This phobia has been exacerbated by the bloody confrontations at public squares.

Place de la Concorde, despite its name, was anything but peaceful during the 1968 student riots in Paris. Palace Square, St Petersburg, will be associated forever with the October Revolution that brought Lenin and the Bolsheviks to power in 1917. Moscow’s Red Square is a vast space [associated] with Lenin’s tomb and bombastic annual displays of Soviet, and now Russian, military hardware. The Plaza de la Revolución, Havana, is where, in his prime, Fidel Castro would address crowds a million strong in the years following the revolution that overthrew the US-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista in 1959. …

On sultry summer or bleak winter days, Tiananmen Square is a decidedly challenging terrain. The might of the People’s Republic was challenged here in 1989 by a popular pro-democracy movement. On June 5 of that year, police and military opened fire, killing hundreds and possibly thousands of protestors. Tiananmen Square is named after Tiananmen Gate, or the Gate of Heavenly Peace. The most haunting image from that horrendous day was that of a lone man, dressed in white shirt and carrying a shopping bag in both hands, facing down and taunting a column of battle tanks rumbling along Chang’an Avenue at the north end of the square. No one admits to knowing who this brave man was or what happened to him: Tiananmen Square swallowed him up.

Recently, scenes of violence concentrated in public squares have been screened in our homes from Tripoli, Istanbul, Cairo and Kiev, and vast parades of political-military power brought to us from Beijing and Pyongyang [Ibid.].

Photo: Geograph

More than a dozen years ago when I lived in London, teaching a class of students from my university, we visited Speakers’ Corner in Hyde Park. A famous public space dedicated to open-air public speaking and discussion, the area near Marble Arch was busy that afternoon, as several Londoners were waiting for their turns to stand on a platform and address the small crowd of listeners who had gathered. But today, the public square as a place of political exchange or protest has been replaced by the internet. Social media has created virtual public spaces where people from all over the world can raise their voices to support their own ideas or, just as often, to attack the ideas of others.

The Huffington Post published a helpful blog from author and radio host Anne Hill that talks about the “ugly shadow” side of social media. She wrote: “Trolling is bullying, plain and simple. It can happen to anyone who gains a large following, especially in tech. And unfortunately, women are often singled out for the worst abuse.”

Social media platforms have become a worldwide phenomenon. But platforms that were praised for connecting people have instead often circulated misinformation and damaging lies, caused irreparable rifts between family members and friends, compounded isolation and heartache for teenagers and others targeted for being different – sometimes leading to their suicides – and created hatred and divisions within the body politic.

A recent article from the Free Speech Project at Georgetown University discusses the good and bad consequences of social media’s functioning as the new public square. On the good side of the ledger, there are positive stories online that celebrate persons for their accomplishments, or even simply for who they are. For example, in 2022 a 7-year-old boy became a viral sensation after a story was circulated explaining his love for corn.

Far more examples of the bad uses or outcomes of social media, however, were highlighted in this study. In December 2021, Rohinga Muslim refugees fleeing persecution in Myanmar sued Facebook for their failure to remove hate speech on their platform which they contended contributed to the genocide of the Rohinga people. In January 2023, Twitter, or X, censored a documentary criticizing the authoritarian regime of Prime Minister Narendra Modi in India, while in December of that year Elon Musk agreed with a tweet accusing Jewish people of “hatred against whites.”

In February 2023, Beatriz Gonzalez and Jose Hernandez, the mother and stepfather of Nohemi Gonzalez, listened to arguments at the Supreme Court in the lawsuit they had lodged against Google for displaying and recommending ISIS videos, which they said contributed to her being killed in a Paris terrorist attack in 2015. In August 2021, a Colorado high school volleyball coach who had been “outed” on social media was forced by the school board to renounce his sexuality or resign his position.

In March 2022, a settlement was reached with a Michigan school superintendent who monitored parents’ social media and exposed what he found to their employers. In April of that year, a Nashville firefighter was suspended for tweeting that the majority of the city council members were white supremacists. In November 2023, a teenager was expelled from school after his mother posted pro-Palestinian comments online. And, in January 2025, Facebook and Instagram suspended their use of fact-checkers.

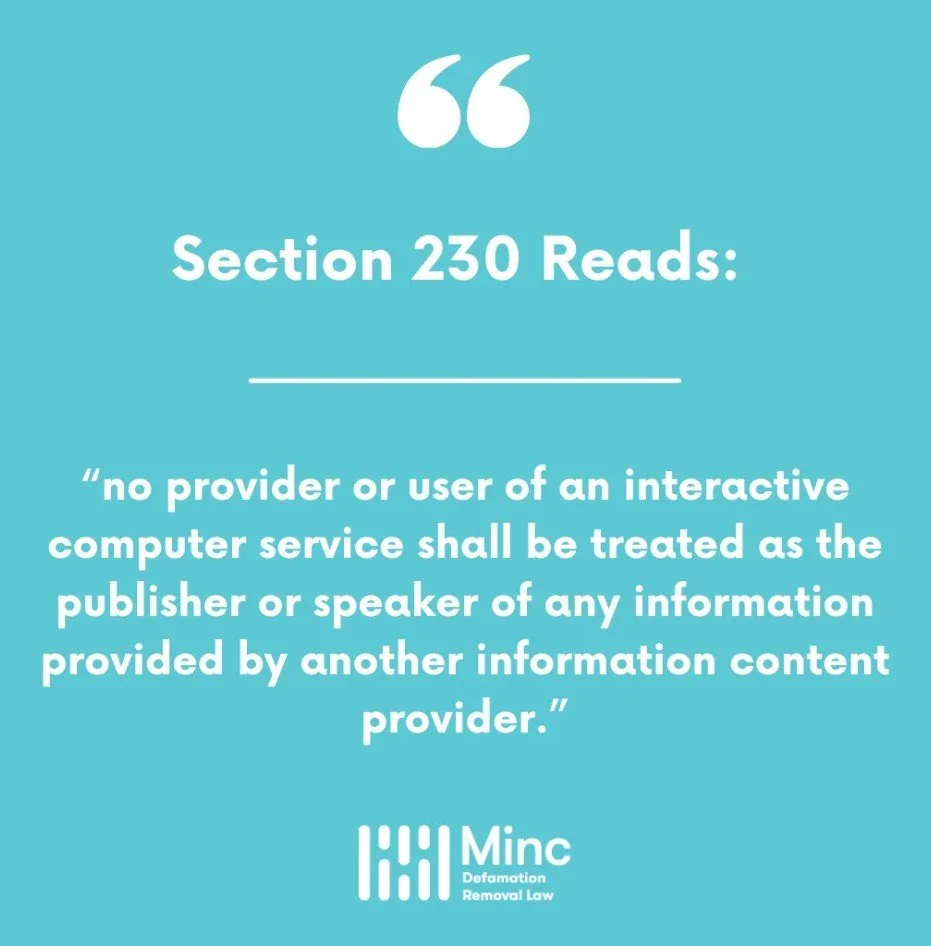

Why can social media distribute hateful, untrue and slanderous comments on their platforms? The reason is because in 1996, Congress passed the Communications Decency Act to encourage internet growth, protect minors from online pornography and remove legal barriers to the freedom of content. Contained within this legislation was the questionable Section 230.

Photo: Minc

What is Section 230, and what has it done to the virtual public square? The Information Technology & Innovation Foundation explains that “Section 230 includes two main provisions: one that protects online services and users from liability when they do not remove third-party content, and one that protects them from liability when they do remove content.” Thus, Section 230 makes it difficult legally to punish those who post hate speech, lies or innuendo online, and the shield it provides to social media trolls or phishing schemers is the source of much debate.

In February 2021 – following the Capitol riots in January – Democratic Senators Mark Warner, Mazie Hirono and Amy Klobuchar introduced the Safe Tech Act, which was intended to change Section 230 of the earlier Communications Decency Act and make Facebook and Google “more accountable for harmful content that leads to real-world violence.” Regrettably, the proposed legislation was never even brought up for a vote in Congress.

So, the anonymous, often brutal, posts on social media continue. We don’t meet in public spaces any longer to watch the executions of political enemies or criminals. Yet, it is not uncommon to have someone lynched or drawn and quartered on Facebook, X or some other media platform.

Anne Hill offers a couple of suggestions for helping to end our own hurtful experiences on social media. She says that, first, we must gain more education about how to avoid the ugly shadow of online trolling. There are excellent articles, she notes, that will give us the tools to follow the advice: “don’t feed the trolls.” Second, Hill recommends that we set a high bar for our own responses to others’ posts. Admittedly, it is tempting to answer with a smoking rant, but we must learn to answer others with equanimity. It is possible to be clear without being unkind.

Are the contemporary public squares, as located on social media platforms today, really “symbols of freedom and democracy,” as the Sandra Day O’Connor Institute declares? Are they still places that allow citizens “to exchange ideas, listen to the view of others, and engage in respectful dialogue,” as public squares were originally designed?

If not, what can we do to help reclaim a more constructive community-building public square in our country?

Header Photo: PxHere