On These Shoulders

High Tea with Marcus and Mary

by Ruth Broyde Sharone

The English landscape rushed by the bus window, lush green hills alternating with roads that twisted and turned through leafy glens.

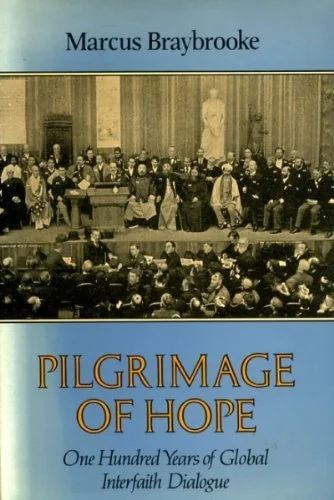

Excitement welled up in me, the possibility of resolving a mystery: Why is the Rev. Dr. Marcus Braybrooke, a retired Anglican parish priest living near Oxford and the author of more than 40 books on interfaith engagement – the acknowledged ‘historian’ of the interfaith movement – known to so few, even within the interfaith movement itself? To be sure, the movement has been spontaneous, not planned, so often the left hand has no idea what the right hand is all about. Still, the author of the classic Pilgrimage of Hope: One Hundred Years of Global Interfaith Dialogue (1993) needs to be known!

Today I was going to tea at the home of Marcus and Mary Braybrooke, hoping to shed some light on the mystery.

Dr. Marcus Braybrooke is president of the World Congress of Faiths, which he joined after receiving his Masters degree in 1964, affording opportunities while he was still young to meet religious luminaries from around the world. He served as executive director of the Council of Christians and Jews from 1984-1988, and he has been Patron of the International Interfaith Centre at Oxford. In September 2004, he was awarded a Lambeth Doctorate of Divinity by the Archbishop of Canterbury “in recognition of his contribution to the development of inter-religious co-operation and understanding throughout the world.”

In the past half-century, Dr. Braybrooke has attended hundreds of conferences and interfaith gatherings, usually as a presenter.

Despite illustrious credentials, though, many in the interfaith community, particularly the newcomers arriving all the time, have not heard of him. In part, Marcus’ natural modesty doesn’t seek outthe limelight. Even at the global conferences, which he still attends month after month, Rev. Braybrooke keeps a low profile. You have to seek him out to find him, and I was about to find him.

My thoughts were interrupted as the bus driver turned to me, indicating we were nearing my destination. Marcus told me on the phone he would pick me up at the Oxford bus station, then drive us to the cottage he shares with his wife of 47 years, Mary, a social worker and a magistrate.

Brahma Kumaris Global Retreat Centre, Oxford

I spotted him immediately – a bespectacled, ruddy-cheeked Englishman, congenial in every manner. Marcus was wearing a tweed jacket, v-neck sweater, and tie, a picture-perfect Oxbridge intellectual straight out of central casting. He wanted to make a quick stop before heading home to show me the Oxford headquarters for the Brahma Kumaris’ community. They recently hosted an “Assisi-like” symposium for world religious leaders. We drove around theirsprawling property while he told me about his long-standing, close relationship with the leaders of the Brahma Kumaris, including their head administrator, Dadi Janki. As I would discover, Marcus is close friends with many world religious leaders.

At the Braybrooke cottage, Marcus’s wife Mary came out to greet me and immediately made me feel at home. Photographs of the family were prominent everywhere in the living room, and their charming caramel-colored poodle, appropriately called Toffee, sat quietly in Mary’s lap during the interview, as well-versed in interfaith etiquette as the rest of the family.

Mary, Marcus, and their dog

Together for nearly 50 years, Mary and Marcus have two children and six granddaughters.

She is his interfaith partner, they both emphasized. In fact, Mary was exposed to interfaith prayer services before she met Marcus, as a teenager attending Unitarian interfaith services in her church. “We thought it was the most natural thing to be working together with people of other faiths for justice and peace,” she says. “Decades later interfaith services suddenly were considered a novelty,” she points out bemusedly. “In the fifties we also studied world religions, but many people today believe that was a much later development.”

Attracted to an Interfaith Model

Marcus traces his interfaith initiation to the sixties, when, after graduating from college, he studied in India with Hindu professors and lived with Hindu families. The year was formative for him, he confesses, especially visiting a leprosy clinic for the poor, run by a Hindu doctor with the help of a Christian from Sri Lanka and a local Muslim. “When I saw in India how religions could come together to help the less fortunate, I was profoundly affected by that interfaith model,” he recalled. “I also found it extremely refreshing and unexpected that the Hindus in India spoke about direct experience with God, at a time when ‘God is dead’ was a catch phrase among Western Christian theologians.”

As a student, Marcus noted that “the academic student of religions may be content with exterior dialogue.” But his mentor, Fr. Murray Rogers, taught that the “exterior dialogue” needed to be accompanied by “interior dialogue” so that listening to people of another faith, observing their spiritual practices and studying their scriptures “should go hand in hand with inner reflection or dialogue with the Lord.”

After being exposed for many years to the idea of “respect for the other,’’ the main mantra of interfaith engagement, Marcus developed his own theory in an article called Mutual Enrichment in Dialogue and Alliance. In it he claims that respect for the other is not enough. Interfaith engagement at its best, he proposes, leads to “Mutual Enrichment” or “Mutual Irradiation” – an approach reflected in his Peace in Our Hearts, Peace in Our World (2012), an e-book.

Mutual Irradiation. His choice of words and their capitalization point to his belief that something of great import can take place in the interfaith process. Indeed, he seems to suggest that, when interfaith engagement is at its best, cellular changes will occur and the people involved will never be the same again.

“Interior dialogue is not a matter of comparing religions or trying to prove the superiority of one’s own faith,” Marcus underscores. “Mutual Enrichment both deepens and broadens one’s faith.” He quotes Christian missionary C. F Andrews, a friend of Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore, who said that through deep contact with other faiths, “Christ has become not less central but more central and universal: not less divine to me, but more so because more universally human.”

“Is religion life-giving or death-bringing?”

In the late seventies Marcus studied for a time in Israel/Palestine and soon afterwards became director of the (British) Council of Christians and Jews. Several of his books reflect the new and growing understanding and friendship between Jews and Christians. In 1997 he co-founded the Three Faiths Forum with Sir Sigmund Sternberg and Sheik Zaki Badawi. In recent years he has given special attention to relations with Islam and counts many Muslims as his friends. “If only we could have responded to the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers and elsewhere with spiritual rather than military force, how different the last decade would have been,” he conjectures.

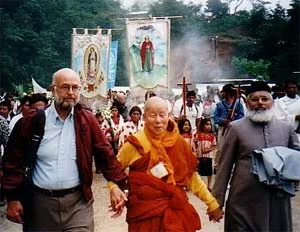

Marcus took this photograph of three other interfaith pioneers, Paul Knitter, Maha Ghosananda, and Irfan Khan, protesting a massacre in Acteal, Mexico.

“The violence of those who acted in the name of Allah was so unlike all that I had learned of Islam, from friendship with Muslims, from reading the Qur’an and above all the inspiration of the Sufis, that I continue to find it sad to see Islam so misrepresented in the media,” he notes, and tells a story. “Some years ago a Muslim explained to me that the inner conflict within the world of Islam is between those who say ‘God is most great’ and those who say ‘Islam is most great.’ There is a struggle for the soul of Islam. So as a Christian I have felt it right to do what I can to help people discover the true Islam. As has been said, the question today is not so much which is the true religion - but what is true religion? Is religion life-giving or death-bringing?”

Marcus Braybrooke’s prose is poetic and lucid as he explores complex subjects with a directness and eloquence that has to be read to be appreciated. In a field where many use quotes for substantiation, Marcus uses them for elucidation and inspiration. He has been profoundly impacted by the people he has met during a lifetime devoted to interfaith activism, and the personal experiences he accumulated, with his wife at his side, have informed his writing as much as his scholarship.

It was time for high tea. I was introduced to Mary’s friend, Susan Dixon, at that time educational officer of the Abbey at Dorchester-on-Thames. The four of us sat down to tea and a table piled high with treats: a walnut cake that Mary had baked for the occasion, as well as chocolate cake, scones, English muffins, butter, and homemade jelly. In short, a sweet, high-caloric bacchanal.

It was a typical and colorful English ritual, celebrated for centuries. For me it was the last lap of my treasure hunt. Marcus Braybrooke, an exceedingly humble man of letters, was no longer a mystery to me. An important scholar, chronicler, and a grass roots activist and delightful raconteur all rolled into one, he will undoubtedly continue to enrich the global interfaith community, however many know him by name.

Highlights from Marcus Braybrooke’s Bibliography

Pilgrimage of Hope: One Hundred Years of Global Interfaith Dialogue (1992)

This is the best history of the interfaith movement available, a 360-page tome surveying a hundred years interreligious relationships in great detail.

Faith and Interfaith in a Global Age (1998)

A much briefer interfaith history is offered here; it continues the Pilgrimage of Hope story through the five years following the 1993 Parliament of the World’s Religions, and it reflects on major themes emerging from this new interplay of the world’s religions.

1,000 World Prayers (2003)

This collection of prayers from all ages and dozens of different traditions is a testament to the spiritual impulse that runs throughout the human family, a river of wisdom and inspiration.

Peace in Our Hearts, Peace in Our World:

A Practical Interfaith Daily Guide to a Spiritual Way of Life (2012)

A practical guide to a peaceful heart and to helping create a more peaceful world. For each day of the year you’ll find a quotation, a meditation, and a suggestion for practical action. It draws on the teaching of many world religions and spiritual traditions while considering the difficulties of the world in which we live. Available only by downloading.

Beacons of the Light: 100 Holy People Who Have Shaped the History of Humanity (2009)

Of all Braybrooke’s books, this may be the best to live with. Short but substantive essays profile 100 religious-spiritual leaders who have made a difference in the story of humankind. They range from Abraham to Krishna, Confucius to Hildegard of Bingen, Aurobindo to Black Elk to Desmond Tutu. Taken alone, each profile is full of interesting information about people that are unknown or just names to most of us. Taken together, the scope and wisdom surveyed here is breath-taking.

Header Photo: Public Domain Pictures