By Kurt Johnson, Robert Toth, and Adam Bucko

MERTON, GRIFFITHS, AND TEASDALE

Father Thomas Merton, Father Bede Griffiths, also known as Swami Dhayananda, and Brother Wayne Teasdale – in the lives and legacies of these three interspiritual pioneers, peacemaking is the congruence between the moral implications of deep contemplative experience (particularly the realization that “there is no separation”) and its reflection in our actions in the world:

- With Trappist monk Thomas Merton we behold this in his lifelong friendship withaHindu monk named Bramachari, a friendship which shaped Merton’s views of both the contemplative journey and the legacy of Mahatma Gandhi.

- With Bede Griffiths in his community Shantivanam, (which means “forest of peace”), we witness such peacemaking in his teaching about theosis, meaning “transfiguration,” an evolutionary vision of humanity at peace in a cosmos of peace.

- And Griffith’s student, Wayne Teasdale, marks “deep non-violence” among his “Nine Elements of a Universal Spirituality,” as well as peacemaking in the life of “full commitment,” described in his classic titled A Monk in the World (2002).

There are many more than these three who have nurtured the dialogue between Christianity in the West and the Vedic traditions in South Asia. On the Christian side of the relationship, though, these three may be the most important spiritual midwives to a 21st century understanding of spirituality, social justice, and East-West religion and spiritual practice.

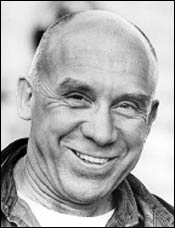

Thomas Merton, Drawn to India

Thomas Merton – Photo: John Lyons, merton.org

As a seventeen-year-old student at Oakham in England, reading reports of Gandhi’s visits to England, Thomas Merton began a life-long study of the Mahatma and his work. Merton recognized the Hindu principles that inform the practice of nonviolence: a commitment to the force of truth (satyagraha), to non-injury (ahimsa), and to action without attachment to results (nishkama karma). In “A Tribute to Gandhi” Merton wrote, “Gandhi’s whole concept of man’s relation to his own inner being and to the world of objects around him was informed by the contemplative heritage of Hinduism, together with the principles of Karma Yoga which blended, in his thought, with the ethic of the Synoptic Gospels and the Sermon on the Mount.”

He concluded: “Gandhi was right, that India was, with perfect justice, demanding that the British withdraw peacefully and go home; that the millions of people who lived in India had a perfect right to run their own country.” Merton would find, as his own life and ministry unfolded, that encounters with persons of deep mystical experience, whatever their religion, would serve to deepen his own experience and faith.

In Merton’s classic The Seven Storey Mountain (1948), he tells that his friend Bramachari counseled, “There are many beautiful mystical books written by the Christians. You should read St. Augustine’s Confessions and The Imitation of Christ.”

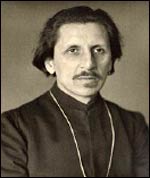

Ananda Coomaraswamy – Photo: Wikipedia

The writings of the Indian scholar and philosopher Ananda Coomaraswamy were also influential. In 1961 Merton wrote “Ananda Coomaraswamy is in many ways to me a model: the model of one who has thoroughly and completely united in himself the spiritual tradition and attitudes of the Orient and of the Christian West, not excluding also something of Islam… Such men can become as it were ‘sacraments’ or signs of peace, at least. They can do much to open up the minds of their contemporaries to receive, in the future, new seeds of thought.”

Bede Griffiths, Also Known as Swami Dhayananda

Father Griffiths’s journey to India as a Benedictine monk, he said, meant finding “the other half of my soul.” Born Alan Richard Griffiths in Britain in 1906, he studied literature and philosophy at Oxford, tutored by C.S. Lewis, who became a life-long friend and spiritual fellow-traveler. After sampling Christian spiritual communities across England, Griffiths, like Merton, embraced the monastic life of the Roman Catholic Church. As a Benedictine, he took the religious name of “Bede” and was ordained a priest in 1940. Griffiths found himself compelled to explore the Eastern mystical traditions, yoga, Indian scripture, and Jungian analysis.

In 1955, a year after writing his first well-known work, The Golden String (1954), Griffiths moved to Bombay. After visiting a number of Indian spiritual centers, he joined other monks in Kurisumala and remained for ten years. During this time he developed activities and liturgies that acknowledged both Hindu and Christian mystical roots. He took up the ascetic life of the Indian “sannyasa,” dressed in the Kavi (the orange robes of the Sannyas), and adopted the Sanskrit name Dhayananda, meaning “the bliss of compassion.”

Father Bede travelled often between India and Europe, initiating East-West dialogue based on another influential book, Christ in India (1967). To further cement this cross-traditional legacy, he located his final ministry at Shantivanam, an ashram in Tamil Nadu founded by pioneer Christian monks working within the Hindu culture and mystical traditions. These included Hindu-Christian icons Father Jules Monchanin and Father Henry le Saux, also known by the Hindu guru name Abhishiktananda.

From Shantivanam, Swami Dhayananda joined with other pioneers in the Christian-Hindu dialogue, including Raimon Panikkar, and published the books Return to the Center (1982) and Vedanta and the Christian Faith (1991). This work became the seed of the “Christian-Ashram Movement” from which came the diverse and influential ministries and activities of his students, including such luminaries as Wayne Teasdale, Andrew Harvey, Russill Paul, and Rupert Sheldrake.

Wayne Teasdale Points to Interspirituality

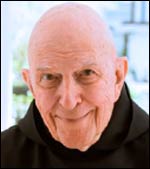

Father Thomas Keating – Photo: Spirituality and Practice

Brother Wayne Teasdale is best known in the West for launching what has become known as the “interspiritual movement.” This began with his 1999 book The Mystic Heart: Discovering a Universal Spirituality in the World’s Religions (1999), where he explored what he identified as “interspirituality” and predicted an emerging “Interspiritual Age.” Teasdale, naming Bede Griffiths and Thomas Keating, founder of the Centering Prayer Movement, as his “spiritual fathers,” wrote the influential spiritual activist treatise A Monk in the World, as well as the best overview of Griffith’s vision: Bede Griffiths: An Introduction to His Interspiritual Thought (2003). A decade later an early colleague of Teasdale, Kurt Johnson, co-authored with David Ord The Coming Interspiritual Age, a detailed elaboration of Teasdale’s thought and activist vision.

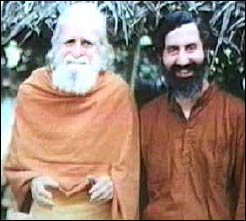

Brother Wayne Teasdale (r.), with Father Bede Griffiths

Combining the heritage of his two mentors, Griffiths and Keating, Teasdale adapted the “Nine Points of Agreement” from Keating’s two decades-long Snowmass Inter-Religious Initiative into his “Nine Elements of a Universal Spirituality.” While Keating’s Nine Points were matters of conceptual agreement across the different traditions, Teasdale’s Nine Elements were matters of character that distinguish both the aspirations and fruits of the contemplative enterprise. In doing this, Teasdale helped solidify Merton’s legacy, bringing into clear focus Merton’s contribution to the post-Vatican II “Foundationalist Discussion,” where he suggested the likelihood of a universal mystical experience common to all traditions – what he called the “communion of mystical-contemplative experience.”

Unhappily, Brother Wayne’s life was cut short by cancer in 2004, just as his work was becoming influential.

There were others, but these three pioneers provide an arena, a template, on which the historically diverse Christian and Hindu traditions can work out their apparent cosmological and theological differences. These divisive disparities were, to the likes of Merton, Griffiths and Teasdale, secondary artifacts of trying to place words and concepts upon the ultimately singular mystical comprehension shared by all. It was to this end that Teasdale dedicated his 2003 explication of Griffith’s interspiritual vision.