The Critical Factor in Interfaith Relations

by Marcus Braybrooke

“West’s war with Islam to last 100 years” was the banner headline of a recent Australian newspaper. Admittedly, the text referred to ‘extreme Islam,’ but the headline reinforces a very dangerous over-simplification sadly too often voiced both by Christians and Muslims on the social media.

On the same day that I saw the headline, thankfully, I started to read His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s recent book, Toward a True Kinship of Faiths. He begins by quoting what Rabindranath Tagore said in 1930: “The races of mankind will never again be able to go back to their citadels of high-walled exclusiveness.” Even now, as the Dalai Lama insists religious believers need “genuinely to accept the full worth of faith traditions other than their own.”

The Dalai Lama tells of his meetings with holy people of different faiths. It was a “crucial learning experience … away from a parochial and exclusivist vision of my own faith as unquestionably the best.” In describing what he treasures from the major world religions he draws upon conversations with believers. For example, when he met the American Trappist monk Thomas Merton, they discussed the centrality of the compassionate ideal of relieving the suffering of others in the figure of Christ and the Bodhisattva ideal.

For the Tibetan people, “the image of Judaism as a religion that has helped a people to survive in exile is deeply inspiring.” The most admirable quality of Hinduism for the Dalai Lama “is the lack of dogmatism when it comes to the conception of the Godhead.” He also respects the “unconditional embracing of God’s absolute transcendence” in Islam.

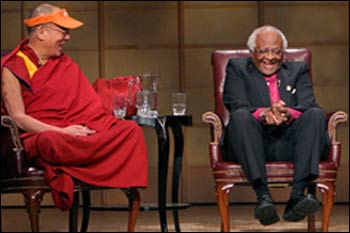

The Dalai Lama and Bishop Desmond Tutu – Photo: Wikipedia

He stresses the importance of personal meeting. “One of the special joys I have come to appreciate in my journey down the spiritual paths of other faiths is the wonderful privilege of opening my heart and hearing the voice of other traditions speaking clearly and directly.” This, he suggests, springs from the fact that all the great religions urge their practitioners “to open their hearts and let compassion blossom as the core message for living an ethical life.” This is why the academic study of religions is no substitute for the personal sharing that interfaith meetings make possible. You can learn about other religions from books, but you are more likely to learn from other religions by personal friendship and conversation with those who lives embody their faith – what has been called “mutual irradiation.”

The Dalai Lama’s words helped me see why I find the discussion about ‘exclusivism,’ ‘inclusivism’ and ‘pluralism’ so arid. It starts from a priori doctrines rather than from “meetings in the cave of the heart.” For example, some years ago when I was in hospital, it was a friend who was a Scientologist who telephoned my wife most days to ask how I was. Again, when we moved to a new job, it was the local Baha’is who arranged a party to welcome us, not the church.

The Dalai Lama himself solves the exclusive-pluralist dilemma by recognising the uniqueness of each religion and its call for total dedication, and by seeing that the diversity of religions is required because human beings are so different. “Just as a supermarket rightly takes pride in its rich and diverse resources of food commodities for sale, in the same manner the world religions can take pride in its rich diversity of teachings.” Such an approach sees the variety of belief and ritual as enriching.

The meeting point of religions for the Dalai Lama is their emphasis on compassion. He tells the story of a Tibetan monk called Lopön-la who spent eighteen years in a Chinese prison. Later in conversation with the Dalai Lama, Lopön-la said there were three occasions when he felt real danger. When asked what kind of danger, he replied, “The danger of losing my compassion for the Chinese.”

The Dalai Lama also quotes the eighteenth-century Indian teacher Shantideva who asked “If you do not practice compassion toward your enemy, toward whom can you practice it?” Too easily, as the Dalai Lama recognises, religion itself – especially exclusivism – becomes a source of attachment and therefore of division, adding bitterness to disputes which have their origin in historical or economic factors.

Only by moving beyond past exclusivism will religions be able to offer humanity the deep spiritual resources to be found in all the great faiths. He ends the book with these words:

For there to be true peaceful coexistence in the world, harmony among the religions is indispensable. Seen in this light, the question of understanding among the faith traditions is no longer a matter that concerns religious believers alone. It affects the welfare of everyone on the planet. Nor is there space left for the secularists and the religious to enjoy the luxury of further bickering. I have always believed that the promotion of inter-religious understanding is not only a response to the call for compassion from my own faith, but also a service to the well-being of humanity as a whole.

There is an alternative to a hundred years of war: cultivating compassion for the enemy.

HH The Dalai Lama, Toward a True Kinship of Faiths: How the World’s Religions Can Come Together (2012).