By Ramy Eletreby

BECOMING FREE TO BE WHO YOU ARE

One of the greatest heartbreaks in my life occurred after coming out at the age of 24: I lost my Muslim community. After my public coming out, via an article in The Los Angeles Times, and the backlash that came with it, I retreated. I distanced myself from the people I cared about, the people I’d been raised with in the masjid in Los Angeles, those whom I viewed as extended members of my own family. I was certain that they had stopped caring about me. It took me years to take responsibility for my part in that break rather than only see myself as a victim of circumstance.

Many Ramadans and Eids went by without seeing any of the friends or elders I had known my entire life. The only relationship I had with other Muslims was with my immediate family – a relationship that was growing increasingly toxic. Though I saw them regularly, I was not being seen. Our conversations always avoided the subject of my life.

The lack of intimacy with my family took such a toll on my mental well-being that I jumped at the opportunity to move to New York City for graduate school. I thought placing the entire country between us would get my family to recognize my value.

What I discovered in New York City was nothing short of a miracle: a vibrant community of queer Muslims, people who gathered together and saw each other as a chosen family. They met regularly to celebrate their shared experiences, whether faith, culture, food, or music, and to support each other against racism, homophobia, trauma, violence, transphobia, and Islamophobia.

Meeting queer Muslims who were in community blew my mind. It took me some time to open up to the possibility of having relationships with other Muslims, something I hadn’t thought possible since coming out. The more people I met, the more I had to reconceive and reposition my own queer Muslim journey. Most of the others had grown up in Muslim-majority countries and struggled with living in societies where they could never authentically be themselves. That had not been my experience. I’d had privileges as an American-born Muslim.

If these people could escape their realities back home and still desire to be in community with other Muslims, then why couldn’t I? Why was I holding on to so much anger and bitterness? I realized that my distance from my community back home and from my faith was a deliberate choice I had made. I could have chosen to stay.

For the first time in several years, I decided to fast during Ramadan. Though it was the toughest fasting experience in my life, thanks to long and hellishly humid days, it was also my most nourishing Ramadan. The holy month of Ramadan is when Muslims seek out community the most, to share in the rigors of fasting, to raise each other’s spiritual connection with God, and to achieve a deeper awareness of the world. Since my family was on the other side of the country, the only community I had was my new queer Muslim friends.

Every morning, after I’d taken my last sip of water before dawn, I prayed to God, crying and thanking Him for giving me back my ummah (Arabic for the global Muslim community). Truly, this ummah in New York felt more like family than any group of Muslims I had been around in years.

A couple of weeks ago I attended another miraculous gathering: the fourth annual LGBTQI Muslim Retreat in Pennsylvania, sponsored by the Muslim Alliance for Sexual and Gender Diversity. We spanned the spectrum of sexual orientations and gender identities and represented over 30 ethnicities and a multitude of paths to faith and religion. We came from across the country, and some came from overseas.

It was the first time I had occupied a Muslim space that was proudly inclusive of all who practiced Islam in whichever way made them feel most comfortable and empowered. As I looked around, I was grateful and inspired. Could I help create more spaces like this at home?

I’m back in Los Angeles now. I want to find a way to serve the queer Muslim community at home. I want to help create more spaces where we can come together and support and learn from each other. I am inspired by the work of Muslims for Progressive Values, an international organization that began in Los Angeles and advocates for the egalitarian expressions of Islam, for women, and for LGBTQI rights. I have so many more people to meet.

Recently, some old friends from the Muslim community I grew up in reached out to me to work on a theater piece. It was an original play called Haram, a tribute to Dr. Maher Hathout, one of the most beloved elders of the Southern California Muslim community. These were people I had estranged myself from and hadn’t spoken to in years. And now they were embracing me.

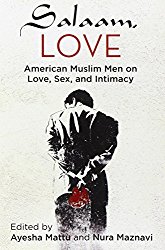

My queer Muslim identity is something I now celebrate. A few months ago, at a Los Angeles reading of selections from the anthology Salaam, Love: American Muslim Men on Love, Sex & Intimacy, in which I share my coming-out story, my Muslim friends whom I’d recently reunited with came to support me and hear me read. As I read the words about my struggle with my sexuality and my community, I looked up. They were all still there, listening to me. They had not run away, and neither had I.

Something changed in these past 10 years. Was it them, or was it me?

This article was originally published by Huffington Post, June 27, 2014.