By Lizann Basshan

ART & DIVINITY

When I was ten years old, a man who owned a small record label wanted to sign me after hearing me sing at a talent show where I went to school with his daughter. My Pentecostal Christian stepmother, bless her heart, was adamant that a gift like mine should only be “used for The Lord, not for the world.” My family moved shortly thereafter, alleviating me from facing the theological dilemma she’d imposed.

I smile and gently shake my head now at her total disconnect between “the Lord” and “the World.” Forty-five years later, having lived most of my ministry as an artist, I fully embrace the conviction that our experience of the Divine, immanent throughout the world, infuses art; and that art, grounded deeply in the struggles and celebrations of this world, offers living images of the deep mystery of Divine presence.

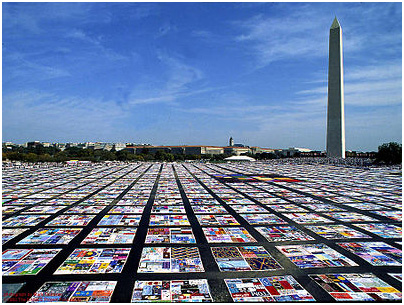

The AIDS quilt project began with 32 who were memorialized to more than 94,000. – Photo (from 2010): Wikepedia

In the 1990s my Christian denomination, the United Church of Christ, was working across the U.S. to bring pastoral care to folk in our churches and in the world who were struggling with the growing AIDS epidemic. We were also doing political and policy advocacy with local and national government agencies. At the time I was a local church pastor working with youth. I’d just moved north to Sonoma County from the Castro district in San Francisco, where LGBTQ rights were being forged. I was immersed in the struggle against the epidemic. Folks who weren’t personally touched by the disease often blocked our efforts based on stereotypes, misinformation, and theological dogma.

In 1996 our local high school drama department mounted a production of “Quilt, A Musical Celebration.” (Jim Morgan, Merle Hubbard and John Schak wrote the play in 1994, with music by Michael Stockler and lyrics by Jim Morgan.)

The musical intertwines stories of the lives of the first 32 people who were memorialized by panels of the AIDS quilt. They differed from one another in ethnic background, age, gender, and sexual orientation. The common thread was their death from AIDS and the profound impact the disease had not only on the lives of those who died but everyone around them. The play is not preachy or heavy-handed but a touching, sometimes funny whirl of relationships, loss, and hope. Because of my work around AIDS and with high school kids and the arts, I was asked to come in as a consultant on the show.

Doing the play had a powerful effect on the lives of students involved in the production, their peers, their families, and our community. A freshman boy, a member of a faith community blocking AIDS advocacy, played the brother of a young gay man who has died of AIDS.

In the story, the brothers come from a homophobic family and an extremely homophobic church. Until the one brother dies, his relatives have no idea that he is gay. The remaining brother tries to make sense of the death and life of his sibling – a life so different from his own, a death so isolated from his family. He eventually changes his attitudes about gay and lesbian people out of love for his brother, who his brother was, and the loving care of his brother’s friends.

In real life, the actor playing the surviving brother came from a similarly homophobic family and church. To his knowledge, he had never met a gay or lesbian person. Through the production, the cast met numerous persons living with AIDS, many of whom were gay. In exploring his character’s reaction, and in getting to know real people who were gay, his own attitudes changed.

Because he was in this play, his entire family struggled with the issue in a new way. Because he was a darling child of his congregation, many people who would not have chosen to see the play were in the audience. Some confided to him later that they had sons or brothers or sisters who were gay or lesbian and had always felt they could not talk about them with church folks. Talking about a play became the gateway for people to begin talking about their real relationships, their deep struggles, their conflicted feelings.

That single exercise in the performing arts – words written, lines spoken, songs sung – changed so many. Its unreal sets and costumed characters reached into the real lives of students, families, and an entire community. It helped inspire me to write a novel, One of Another (2008) around the same issues. In short, the production of that play became a place where the Divine and the World swirled and danced together beautifully.

Certainly my stepmother’s particular interpretation of theology and the arts (“... gifts need to be used for the Lord, not for the world”) is echoed in many religions and faith traditions, not just conservative Christianity. But after all, it turned out that “Quilt, A Musical Celebration” was indeed “used for the Lord,” offering grace and love to an abused community and fostering reconciliation. Through my work as a minister, writer, musician, and director, in communities and groups that identify primarily as artists, as well as communities that identify primarily as religious or spiritual, I overwhelmingly find the boundaries and lines pretty blurred.

Yiddish dancing had a role in BeArtNow – Photo: psr.edu

Those blurred lines of swirling dance were joyfully celebrated this past January at the 2015 Earl Lectures and Leadership Conference sponsored by Pacific School of Religion (PSR) in Berkeley, California. PSR is a historically Christian seminary that is slowly morphing into a more multi-faith seminary. The theme was BeArtNow, billed as a “public conference for activists, artists, & progressive people of faith.”

The experience lived up to its promise: “Performances, exhibits, worship space, public arts, and liturgies invite you to step inside revolutionary spaces where arts are transforming the world and to explore innovative ways to integrate art into your vocation and spiritual life.” Three days were filled with performances and lectures by scholars, artists, and activists. Immersion experiences in Bay Area community arts projects working on social justice issues were offered. Workshops addressed CircleSinging; gallery art as writing-prompts for poets; using art in indigenous rights activism, and more. It was a three-day celebration of that swirl and dance of the Divine and the World.

May the dance continue. May our experience of the Divine, immanent throughout the world, continue to infuse our art; and may our art, grounded deeply in the struggles and celebrations of this world, continue to become living images of the deep mystery of Divine presence. Dance and swirl, dance and swirl.