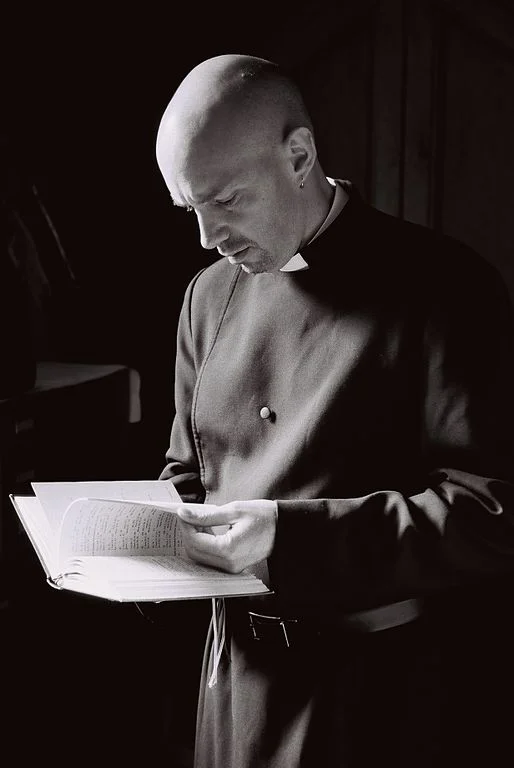

The Rules for What We Wear

What do Clothes Tell Us?

by Marcus Braybrooke

An Anglican priest wearing a double-breasted cassock – Photo: Wikimedia, Anne Jeff

The vicar of the parish where I was a curate always wore a cassock. He said it was “the only classless garment.” He did not wish to be identified with either the wealthy or poorer members of the parish. I had not at the time realised how quickly people form an opinion of you by what you wear.

I am reminded of this because the elite MCC (Marylebone Cricket Club) at Lords has just warned members that they will not be admitted if they wear ‘Thongs, scuffs, dilapidated footwear, gumboots, moccasins, slippers and ugg boots (look on the web if you don’t know what they are), torn clothes, even if designer’ tears, bikini tops and tops showing bare midriff,” and, which I welcome, any clothing displaying racist or similarly offensive messages. National costume and religious requirements such as a clerical collar are acceptable.

Clearly, Britain is still very class conscious.

The Muslim hijab or scarf is often black, but these women at an engagement party in Brunei demonstrate how colorful they can be. – Photo: Wikimedia, Cc.2.0

More important, however, was the recent ruling by The European Court of Justice that companies can ban employees from wearing the Islamic headscarf, if the prohibition applies to all religious and political symbols. The case arose as a result of a Muslim woman being told she could not wear a hijab at work. She protested that this was religious discrimination, but the Court, rather ambiguously ruled that a headscarf ban may be “indirect discrimination” if people adhering to a particular religion are disadvantaged, but that indirect discrimination is permissible if a company's policy applies to all its workers.

The reaction to the ruling has been very mixed. One French presidential election candidate hailed the ruling as “an immense relief” that would contribute to “social peace”: but a campaign group backing the women said it could shut many Muslim women out of the workforce. The United Sikhs advocacy group said the “disturbing” ruling allowed employers to override fundamental human rights.

The question in France is not only what you should wear at work but what you should wear on the beaches. Last summer, 26 French towns on the Riviera banned women in full-body swimsuits known as ‘burkinis’ from the beaches. Human-rights campaigner said the burkini ban would increase segregation and was illegal. The mayors, who had made public-order decisions in the aftermath of the terrorist attack on Nice, said the bans were protecting public order and rules on secularism. The French prime minister backed the mayors, adding that the burkini represented the “enslavement of women.”

The State Council, however, disagreed, and its vice-president said that the country’s supreme court “obviously” had no right to tell French people what they could and could not wear to the beach. (Many beaches in Britain are so windy that everyone covers up!)

There have been similar arguments in Britain over whether a Christian can wear a cross at work. A Christian airline check-in clerk had been barred from wearing a cross, but in 2013, she won the right to wear a cross when The European Court of Human Rights ruled that the UK had failed to protect Nadia Eweida's freedom to manifest her faith in the workplace. The UK Government had argued that the ban was not a breach of human rights and that wearing a cross is not an essential tenet of Christianity. But in its judgment, the Court said that manifesting religion is a “fundamental right.”

The Court, however, rejected a similar legal challenge from Shirley Chaplin, a nurse. It ruled that the hospital where she worked should be able to refuse permission to wear a cross on “health and safety” grounds.

The Consequences of Banning Religious Garb

A Sikh wearing a dastar or turban to cover his hair – Photo: Wikimedia, Yann, Cc.3.0

The issue of what we wear is important because of the lasting hurt that can be caused by rulings or abusive remarks about what one is wearing. Moreover it marginalises small faith communities. In many societies, Sikhs have struggled to be allowed to wear their turbans. In Britain, it took time for bus conductors to be allowed to wear turbans. Then Sikhs were exempted from wearing crash helmets and quite recently new rules mean Sikhs across the UK will no longer face the prospect of disciplinary action for wearing turbans in the workplace. For more than 20 years, Sikhs working in the construction industry had been exempted from rules requiring head protection – but because of a legal loophole, those in less dangerous industries, such as those working in factories and warehouses, were not.

Of course, clothing can be a security risk. In 2002, two assailants in burqas threw a grenade among worshippers at a Christmas Day service in the village of Chianwala, northwest of Lahore, killing three and wounding thirteen. But then the Dalai Lama escaped from the Chinese who had taken control of Lahsa by dressing as an ordinary soldier.

Clothes matter, they affirm our identity and often our religious commitment, and in an open society I think people should be free to wear what they want. Sensitivity to other people is also of vital importance in a genuinely open society in which everyone feels at home.

Telling someone yesterday that I was writing this article, I was asked, “Do Sikhs wear their turbans in bed?” The answer at www.answers.com was “Some do, some don’t.” I never asked my vicar whether he wore his cassock in bed.